Finally, the West gets a glimpse of Arabic literary riches.

When Egyptian Naguib Mahfouz won the 1988 Nobel Prize for Literature, it was not only the first time any author in Arabic had received such broad and prestigious recognition in the West, it was the first time Arabic literature itself had come to the attention of the general Western reading public. The fact that the first Arab writer to be so acknowledged—and to be widely translated into English—was Egyptian is not surprising, since Egypt has traditionally been die center from which cultural forms ranging from the novel to the film, from the short story to the soap opera, have been disseminated to all parts of the Arab world.

Mahfouz, author of more than 40 novels and short story collections read throughout the Arab world, masterfully refined the European novel into a dominant genre of modern Arabic literature. His fiction is intensely "Egyptian," portraying the lives of individuals and families in specifically Egyptian contexts, and mapping the modern development of Egypt. Yet his work is by no means provincial. A recurring theme in his fiction is that humans learn ways of surviving, only to find that the rules have changed, at which point their survival strategies backfire. His characters repeatedly place their faith in people, traditions, beliefs, or ideologies, only to be disappointed, disillusioned, and betrayed.

While Mahfouz is Egypt's master novelist, Yusuf Idris, the second most widely translated Arabic author, is considered by many to be the master of the short story in Egypt. Idris's stories are piercing, dramatic, and intensely intimate. In language fluctuating between "high" or more formal literary Arabic and spoken or colloquial Arabic, he portrays the passions, frailties, and mysteries of life with brutal honesty.

But Egypt is not Arabic's only cultural sphere. For all that binds the countries of the Arab world together historically, politically, and linguistically, there is enough that substantially distinguishes them to have given rise to various distinct strands within the overall modern Arabic literary tradition.

There is, for example, a distinct and rich Palestinian literary tradition. In poetry, short stories, and novels, uniquely Palestinian themes and motifs recur: displacement, exile, fragmentation, homelessness, and a nostalgia for die lost homeland conveyed through romantic and often painful yearnings. In the fifties and sixties, Palestinian literary works expressed despair and hopelessness, and eventually criticized Palestinians' acceptance of their fate. Literary works increasingly embraced issues of solidarity and resistance, portraying their risks, failures, betrayals, and heroism, and the development of Palestinian national consciousness. In the seventies highly sophisticated works used caricature, satire, and wild farce to portray the Palestinian tragedy.

In Lebanon, where writers have long contributed to the overall Arabic literary tradition, the past two decades of civil war have produced an outpouring of literature, a significant proportion of which has been written by women. These works present the disintegration of all trappings of stability, the uncertainty and fragmentation of life under these circumstances, the übiquity of death, the abnormality of most people's "normal" lives, and the numbing of the senses necessary for withstanding constant exposure to horror.

The countries of North Africa, or the maghreb, (Tunisia, Morocco, Algeria, etc.) have produced still other distinct literary strands marked by the legacy of the French colonial presence in those countries. While some of this literature is written in Arabic, much of what is considered the vanguard of modern. North African literature is actually composed by Arabs in French. More of this "Francophone" literature has been translated into English than the literature composed in Arabic. Controversy persists about authenticity and cultural identity in French "Arab" literature, but this tension itself has vitalized the work.

In the Sudan, a small number of Arabic authors grapple with similar issues of identity and authenticity in the wake of British colonialism as they portray the conflicts, rage, and confusion that are the by-products of colonial "forced marriages," such as that between England and the Sudan.

Much of Arabic literature remains hidden from view in the West. Works by Saudi Arabian authors have only very recently been translated into English and works from other Arab countries, including Iraq, Jordan, Syria, and Yemen remain largely unavailable in English. Even less visible is the body of "unofficial," largely unpublished Arabic literature that circulates by means of underground presses, cassettes, or live oral performances outside the grip of the extensive censorship found in most Arab countries today.

Arabic Professor Carol Bardensteinsees Arabic literature as a gatewayto the complex Arab world.

There was no genie or flying carpet, but when Carol Bardenstein took a highly-touted course in Islamic history at the University of Michigan back in 1976, a kind of magic happened. What began as a distributive whim for the then-biology major became the first step towards a professorial love affair with Arabic language and literature. There were many points Middle Eastern in between. While still an undergraduate, Bardenstein spent her junior year in Jerusalem. In addition to studying Arabic and Islamic history that year, she got to know the family of a Palestinian friend she had met in her hometown of Detroit. "I began to see how Arabs in the Occupied Territories really lived: the checkpoints where Arabs were stopped, the staccato commands—Go, Come, Give—of Israeli soldiers checking

their papers. I didn't expect what I saw," she says. After graduating fromMichigan as a Near Eastern Studies major, Bardenstein spent two more years in Jerusalem, then earned a Michigan M.A. in modern Middle Eastern politics. In 1982 she arrived at Cairo's Center for Arabic Study Abroad. "I fell in love with the Egyptian dialect of Arabic," she says. With that her career leapt forward: she began studying modern colloquial Egyptian lit- erature—including its oral form—in addition to formal Arabic literature. The road from Cairo led to Dartmouth, where in 1987 Bardenstein became the College's first professor of Arabic language and literature. Her classes and her film-and-food "Tahina Times" get-togethers attract a steady stream of students. Last year Bardenstein offered another taste of Arabic: a course about western transformations of the 1001 Arabian Nights stories—from Matisse's Odalisque to musical Scheherazades to the British Christmas pantomimes Bardenstein studies in an ongoing research project. Even Charles Dickens felt the pull of Arabian Nights, the professor explains. "He wrote that in his stories he tried to create the same wonderment he felt when he first read ArabianNights as a child, that he tried to find the magical in the mundane." Bardenstein could use a little of that magic now. The new Michigan Ph.D. just returned from a troubling visit to Israel's Occupied Territories. The magic might help her tell the stories, more tragic than mundane, that need to be told. :—Karen Endicott

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

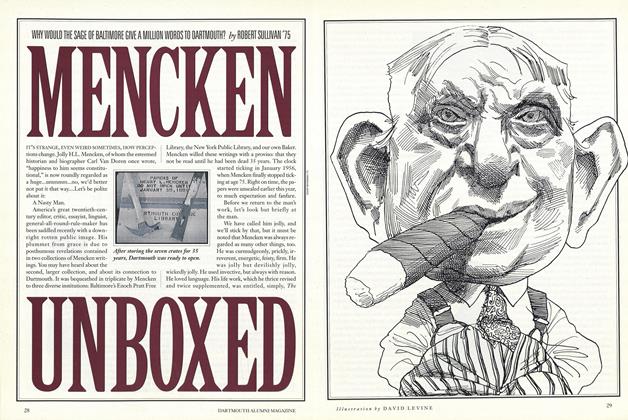

FeatureMENCKEN UNBOXED

October 1991 By ROBERT SULLIVAN '75 -

Feature

FeatureHONEST TO GOD ACCOMMODATION

October 1991 By JAMES O. FREEDMAN -

Feature

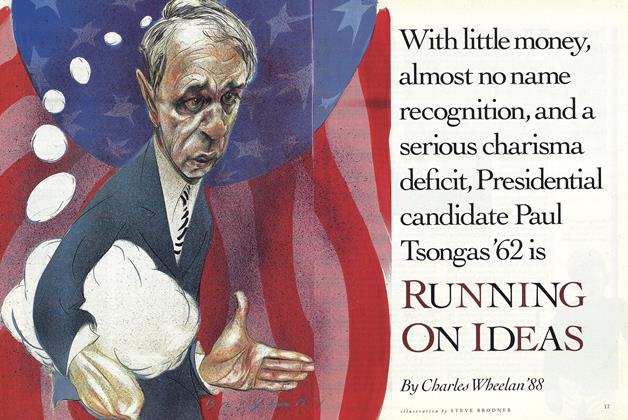

FeatureRUNNING ON IDEAS

October 1991 By Charles Wheelan ’88 -

Feature

FeatureThe Masked Stork

October 1991 By William DeJong '73 -

Feature

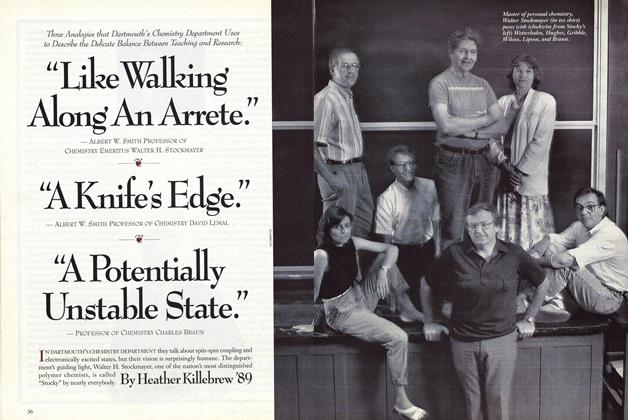

Feature"Like Walking Along an Arrete."

October 1991 By Heather Killebrew '89 -

Article

ArticleDR. WHEELOCK'S JOURNAL

October 1991 By E. Wheelock