A KIND AND interesting letter from Ken. neth Roberts from Italy throws some light on the research that he does to make his historical novels accurate. He writes that he had gone to Algiers "to run down verification of the statement made to Wheelock by Robert Rogers about the Dey of Algiers." The letter continues: "The French Department of Antiquities went through the records with a fine-tooth comb, but the pump is still sucking wind. It's odd that every historian has always accepted a statement made to Wheelock by Rogers in the wilds of New Hampshire, and that not one has ever been able to verify it." Of such painstaking desire for the truth are great historical novels made. Mr. Roberts has also discovered, he thinks, in Chase's History of Dartmouth College, that Benedict Arnold was one of the first subscribers to Eleazar Wheelock's Indian School and this fact will be inserted in the newest edition of Rabble in Arms. If you haven't read this fine story do so by all means. It is a book to possess.

Apropos of Arnold, Paul Allen of the library staff informs me that in the Dartmouth archives there is a letter from Wheelock thanking Arnold for his subscription.

A good letter from Herb Heston '34 in which he recommends Great Winds by Ernest Poole. "I think it is the best book I have read since graduation," he writes.

For this last issue of the year I intend to review briefly several books that, for lack of space, I have been unable to include in previous browsings, and to include a few recent books that have interested me.

My-new-author-of-the-month is George Blake, a Scotsman, who seems to me one of the most promising of contemporary writers. His The Path of Glory I mentioned in the April issue. For fifteen years he has written the Vagabond Papers in the Glasgow Daily News, and was one time editor of the Strand Magazine. With the English Book Society choice for March, Mr. Blake has arrived as a major writer. This book, The Shipbuilders, is one of the best novels I have read for a long time. It deals with the shipyards of the Clyde in the more recent years of the depression. The action takes place a few months before work was recommenced on the Cunarder 534, since christened the Queen Mary. The plot revolves around the owner of the yard, a young Major in the war, and his war-time batman Danny Shields, a riveter in the Major's shipyard. The gloom that is now Glasgows is most excellently portrayed. In Danny Shields, Mr. Blake has created a memorable character. Descriptions of a great football match, of the launching of a great liner (the last the yard builds), and of the impact of the depression on the workmen, are brilliantly drawn. Mr. Blake will bear serious watching, and information from England informs me that wise collectors are now getting Mr. Blake's earlier books, of which there are at least a dozen.

Again I recommend Hell Hole of Creation, by L. M. Nesbitt as the best travel book of the year. Don't miss it. Knopf is the publisher.

Philosophical Ideas in the United States. by H. G. Townsend. American Book Company, 1934.

A readable and clear exposition of the leading ideas in American philosophy from Jonathan Edwards to George Santayana and John Dewey. Not easy reading for the general reader but comprehensible to anyone with an elementary knowledge of philosophy. There is an adequate bibliography at the end.

The Conquest of the North Pole, by J. Gordon Hayes. Macmillan. 1934.

Mr. Hayes has written a volume dealing with Antarctic exploration, and also a study of Peary's explorations, and in this third book he deals with the Arctic.

Many of the most successful and scientific explorers are generally unknown to the public, for they desired no publicity and toiled disinterestedly for science. Mr. Hayes summarizes their exploits and their findings. Among those discussed are Mylius-Erichsen who explored and perished in Greenland, Rasmussen, Steffansson who will be remembered for his Dartmouth lectures of some years ago, Binney and his Oxford expeditions, Wordie and his Cambridge expeditions (recent "school boy explorers"), AndnSe and Nobile, Nansen the greatest of all northern explorers, and Gino Watkins, who lost his life in 1931 while paddling a kayak.

The most startling theory in the book is that Peary never reached the North Pole. The author bases his judgment on records well known to explorers, who, he suggests, are naturally reticent about bringing forth their opinions. Peary to have reached the Pole would have had to traverse 150 miles of polar ice in two days which from all previous experience, including that of Peary, was impossible. Whatever the merits of Mr. Hayes's arguments many explorers agree with him.

First and Last, by Ring Lardner. Scribners, 1934.

Neither the publishers nor the editor did Ring Lardner any particular service in publishing this potpouri. The Lardnerian note is authentic in several places, notably in On Conversation (pages 243ff.) and The Young Immigrants.

Artists in Uniform, by Max Eastman. Knopf, 1934.

Mr. Eastman writes: "My subject is creative art, and creative art in those deeply felt and thoughtful regions, where, if it is to flourish, it must inevitably assert to some extent its independent rights. And my theme is that every manifestation of strong and genuine creative volition, every upthrust of artistic manhood, in the Soviet stamped out, or whipped into line among the conscripted propaganda writers in the service of the political machine." He gives the slogans of the Artist's International which are: art is to be collectivized; art is to be systemized; art is to be organized; art is to be disciplined; and, art is to be created "under the careful yet firm guidance" of a political party. Mr. Eastman believes on the other hand that art demands a lonely and personal effort and that the artist must be free. He discusses the suicides of Yessenin, Maiakovsky, and others, and tells of the "humiliation of Boris Pilnyak."

Communism uses the human spirit only to further its "Holy Purpose"; all else is bourgeoise and must be stamped out. Individualism or a free spirit creating or thinking for itself finds little or no place in a state controlled by a dictatorship whether it be fascist or communist.

The Marxian critics here didn't like Mr. Eastman's book but their only defense, so far as I heard, or read, them, was to call the author names. His statements for the most part are records on the books.

Mr. Eastman is one of the speakers on the Guernsey Center Moore Foundation for this vear.

Impassioned Clay, by Llewellyn Powys. Longmans, Green & Co. 1931.

This is a beautifully written exposition of a pagan-naturalistic point of view. Mr. Powys is in the Epicurus-Lucretious tradition, and what he has to say has much sense. His own extreme lust for life is partially due, I think (as it was in D. H. Lawrence), to his own struggle against the ravages of tuberculosis. This is a book for youth but older men will be pleasantly moved by the style, perhaps a trifle ornate, of Mr. Powys.

I might remind my readers that Llewellyn Powys is the best, for me at least, of that talented triumvirate of brothers which includes beside Llewellyn, John Cowper Powys (whose recent Autobiography is well worth reading), and Theodore F. Powys, whose most recent book of short stories is Captain Patch.

Too True to Be Good, Village Wooing, and On the Rocks. Bernard Shaw. Constable, London. 1934.

Shaw, though he is repeating himself, is still one of the best minds in England. These plays can scarcely be considered drama but they are crisp and amusing dialogues well worth your attention.

Memoirs of a Polyglot, by William Gerhardi. Knopf. 1931.

This is a clever autobiography of a young man now 39. He was a friend and contemporary of Joseph Brewer '20 during the years Joseph was at Oxford.

Mr. Gerhardi grew up in Russia and he tells of the revolution with understanding and without the sensationalism of the "British agent."

The author is honest, cynical, and witty in the Oxford manner, and he recounts many amusing anecdotes of several great contemporaries in the world of politics and literature. This is an interesting book and one I missed when it was first published.

Forty-two Years in the White House, by Irvin Hood Hoover. Houghton, Mifflin Co. 1934.

You have probably read this book of revelations about the intimate lives of the presidents and their wives from Harrison to Hoover. "Ike" Hoover was chief usher in the White House from the early nineties to his death in 1933. This is, you might say, the "low down," and comic, and sad at times, it is, too.

Mr. Coolidge, suitably immortalized by Gluyas William's famous cartoon, does not come out too well under the chief usher's shrewd and sardonic glance. Mr. Coolidge, the author hints, had the Yankee's reverence for wealth, whatever its source, and Mr. Hoover is convinced that his "I do not choose to run" meant that he desired the party to renominate him, and when it did not do so, he was never the same man again.

The author airs the linen of the White House but in no scandalous manner. Will Rogers comes in for some amusing legpulling.

Slim, by William Wister Haines. Little, Brown and Co. 1934.

Slim will take you into the world of the worker who strings up wire for the great power systems, and who electrifies whatever railroads that still have capital enough to electrify their lines. After reading this book you will never be able to pass the great towers cutting across the country, carrying immense POWER, without marvelling at the immense energy, courage and skill involved in putting them up. This book, then, is the romance of a linesman. It tells of his work, his talk, his fights, his lovemaking, his crap-shooting, his poker playing, his simple philosophy, his professional pride, his skill, his humor, his travelling, his technique, and anything else you wish to know about the man who is doing pioneer work in this country.

This story of a skilled workman has an epic quality reminiscent of Mark Twain's memoirs of the life of a pilot on the Mississippi. There is a quality in Mr. Haines' book, a truly American one, which reminds me of Mark Twain. Mr. Haines, to use the parlance of the trade, knows his stuff. He has been a linesman for seven years himself.

There are some high spots in the book that a reader will not soon forget as, for example, the brutal fight with the gamblers, Slim's battle with Wilcox, his first "bender" with chorus girls in Chicago, and the shocking death on the "hot" wire. The healthy masculinity of the book is most atti active and it stamps the book as a genuine piece of Americana. It is not hardboiled in the Hammett manner. You will like this book.

European Journey, by Philip Gibbs. Doubleday, Doran. 1934.

As a companion volume to Mr. Priestley's English Journey the publishers now offer Mr. Gibb's European Journey. In 1934 the author motored through France, Switzerland, Italy, Austria, Hungary, Germany, and the Saar where he interviewed many ordinary people in order to get their views on conditions in Europe. The result, though not sensational, nevertheless gives one serious cause for thought. One of his companions, Mr. E. Lander, made some excellent pencil sketches which add a great deal to the value of the book.

I shall allow Mr. Gibbs or his interlocutors to speak for themselves:

i. "When Youth decides to do something about it, it seems quite likely that they will do the wrong thing, in different colored shirts, with different war cries, with new hatreds, with new intolerance towards their fellow men." (Page 109.)

2. "Monsieur, it is because the Machine is manipulated by greedy men for their own profit. That I believe is the answer."

3. "Many little Fascists are coming into the world at a time when high-souled men like Signor Mussolini are of opinion that 'Peace is detrimental and negative to the fundamental virtues of man.' At six years of age these babies will be enrolled in the Balila, for their preliminary training in this philosophy. They will sing the Song of Youth and salute the Fascist flag as the symbol of the State, which later on they must obey with blind obedience." (Pages 141-142.)

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Sports

SportsFOLLOWING THE BIG GREEN TEAMS

June 1935 By C. E. W. "30 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1934

June 1935 By Martin J. Dwyer, Jr -

Article

ArticleWAS THE PROFESSOR RIGHT?

June 1935 By Eric P. Kelly '06 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1932

June 1935 By Charles H. Owsley, II -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1933

June 1935 By John S. Monagan -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1905

June 1935 By Arthur E. Mcclary

Herbert F. West '22

-

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

May 1938 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

November 1942 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

May 1943 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Books

BooksWAR BELOW ZERO

December 1944 By Herbert F. West '22 -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

February 1946 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

April 1949 By HERBERT F. WEST '22

Article

-

Article

ArticleFaculty Takes Coeducation Stand

MAY 1971 -

Article

ArticleTurning the Tide

NOVEMBER 1998 -

Article

ArticleDiary of a Freshman

March 1933 By A. P. Butler '36 -

Article

ArticleThe College as a Cooperative Enterprise

OCTOBER 1931 By Ernest Martub Hopkins -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

November 1936 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

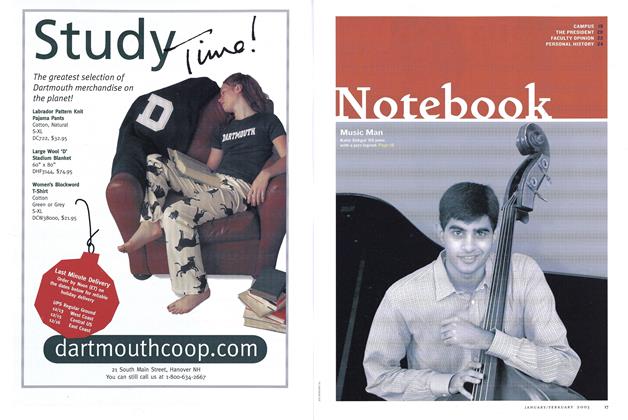

Article

ArticleNotebook

Jan/Feb 2003 By JOE MEHLING '69