On the top of a hill in Windsor, Vermont, sits a Zen garden with a turbid reflecting pond, stones, and two winding paths of manicured sand. There is also a dining hall, a woodshop, dormitories, and a schoolhouse, all built to accommodate the gardeners, who are the inmates of the Windsor Correctional Facility. Off and on for the last three years I have been one of their Tucker Foundation tutors.

I became a Prison Project volunteer the fall of my first year at Dartmouth. I remember calling home and casually mentioning that I was going to tutor at a prison.

"Jail?" my mother said.

"You're going to a jail? Couldn't you go to an elementary school instead? People who commit crimes go to jail."

After assuring my mother that my record was clean, I dutifully answered her "I'm concerned for your safety" questions. No, I would not be alone in a cell with Hannibal Lecter. Yes, I would be careful not to be duped by some suave con artist. Yes, I really did think that I had a lot to teach some underprivileged, undereducated criminal longing for guidance.

I found out much later that I was radically wrong. I got the part about being safe right, but I also committed the crime to which I am most susceptible: naive altruism.

My students at Windsor were able to set me straight. Mike and Joe are working to improve their math skills for the G.E.D. (exam. Four other students took creative writing from me this summer. With them I have dissected William Carlos Williams and word problems, studied multiplication tables and the lyrics to "With or Without You." I have co-written a story about an émigré Vermont farmer who owns 365 Chicago Bulls T-shirts and walks with an ornate cane. I have graded poetry and final exams.

Some of my students would be indistinguishable from my fellow '95s. Not all are hardened, sinister criminals. Nor are they all some Hollywood version of Clarence Gideon— good, earnest souls maligned by "the system" and seeking salvation. In fact, they are not an "all," but rather a series of "I's" in a kaleidoscope of personality. Some study to better them-selves; some study to impress the parole board; some don't study at all. They have a range of backgrounds and experiences and intelligences; they recite Shakespeare and Dr. Seuss, quote Aristophanes and Gunsn- Roses. Many struggle to conquer learning disorders, drug and alcohol problems, or childhood traumas. Through my experiences I have gradually been disabused of the myth of the unfortunate, downtrodden "them" rescued by the omniscient, philanthropic "us." As a tutor, I do not ride up on a white horse and bestow grace; I drive my Honda and I teach and learn, get frustrated, excited, bewil- dered, inspired.

I've accrued tangible rewards from my years at Windsor: the clever short story our class wrote together, the first midterm I ever gave (A-1), and Joe's thank-you note after passing his high school equivalency exam. Each of these is important to me, and on occasion they swell my ego when I'm having a difficult day or questioning my impact in this intimidating world. I know that I will always remember my experiences teaching at Windsor. But ultimately, it will be my experiences learning—particularly about the elusive concept of community—which will resound through and inform the rest of my life.

VOLUNTEER WITH DARTMOUTH COMMUNITY SERVICES AT THE TUCKER FOUNDATION.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryNO HOLDS BARD

March 1994 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

Feature

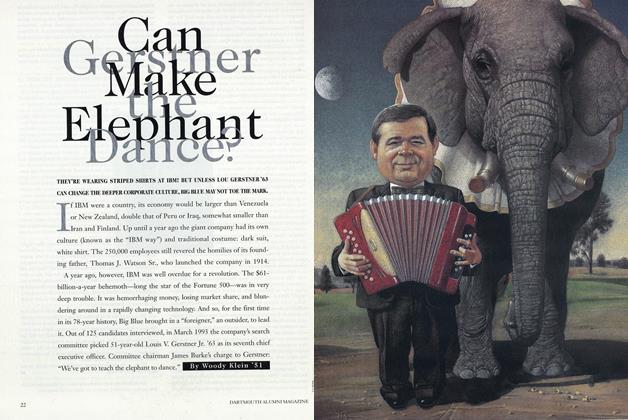

FeatureCan Gerstner Make the Elephant Dance?

March 1994 By Woody Klein '51 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1980

March 1994 By Daniel Zenkel -

Article

ArticleDr. Wheelock's Journal

March 1994 By "E. Wheelock" -

Class Notes

Class Notes1975

March 1994 By W. Blake Winchell -

Class Notes

Class Notes1993

March 1994 By Christopher K. Onken

Article

-

Article

ArticleHungry for Information

July/Aug 2002 -

Article

ArticleHockey

January 1954 By CLIFF JORDAN '45 -

Article

ArticleFootball

July 1955 By Cliff Jordan '45 -

Article

ArticleParis

OCTOBER 1962 By DIDIER PINEAU-VALENCIENNE ’56T -

Article

ArticleLaureled Sons of Dartmouth

February 1945 By H. F. W. -

Article

ArticlePENSIONS AND PROGRESS

May 1912 By Sidney Bradshaw Fay