THE UNSUNG BUT NOTABLE WORK OF "B." SMALLEY '94,EDITOR FOR A MILLION READERS MONTHLY

"Let us now praise famous menMen of little showing." ....

RUDYARD KIPLING.

THERE HAS always seemed to be a trifle of inconsistency in Mr. Kipling's quoted verses; and yet nothing could be more appropriate as describing the work of Bertrand Adoniram Smalley (Dartmouth 1894), who recently retired, under the age-limit requirements of the New England Telephone & Telegraph Company, from his position as publicity manager, which he had held since 1923. For Mr. Smalley's best work was anonymously done. He served a great and growing public which read his words and sent him tons of what the argot of our day calls "fan mail" without so much as knowing his name.

Trained as a newspaper man in the days before toilers in that vineyard had come to feel that they must sign their stuff, under what the trade calls a "by line," Mr. Smalley was well content with his anonymity. He gave of his best, and took no personal credit for it. His identity was merged in the company which he served, just as it had been when he was a reporter and editor in Boston. Surely it is high time a bit of applause were given to this extremely competent and conscientious performer! His chief task, among many, was the production of a little four-page leaflet entitled "Between Ourselves," which the Telephone Company printed and sent out with its monthly bills, designed for the information and entertainment of all subscribers. Mr. Smalley's congregation numbered close to a million persons a month; and as was said of a much greater preacher, "the common people heard him gladly."

These little monthly "talks" were couched in what their author called his "cracker-barrel" style that is the humorously whimsical style of the country-store commentator, than which there is no better method for communicating ideas to the general world, if so be it is not overdone. Common sense, expressed in terms which common sense people can readily absorb, finds thus its most effective channel. It is the antipodes of Gilbert's aesthete, who voiced the belief that

If this young man expresses himselfIn terms too deep for me,Why, what a very, very deep young manThis deep young man must be."

Mr. Smalley's monthly leaflet put things pungently and directly. The idea was to produce a monthly mailing-piece which should combine advertisement with the promotion of good will among the customers. Whether or not the same sort of publication would have been as effective in other parts of the country does not concern us. This was a New England job, done for New England people, among whom Mr. Smalley had grown up and whom he understood. He knew his public, and how to appeal to it. As he puts it himself, the idea was always to write for one definite man, and not for a multitude a practice which many preachers and lecturers have found useful.

LEAFLETS WELL READ

Moreover the "stuff" was good. Mr. Smalley never allowed his monthly chats to degenerate into sales-patter. It was an avenue of communication between the servant and the served, conveying matter of interest to both—proposed changes in the method of handling details of the telephone business which directly affected the customer, of offering explanations of problems as to which inquirers had written in, or finding some other way for securing co-operation which would promote efficient service. People not only received these leaflets month after month they read them. Few among us are accustomed to look forward with joy to the arrival of our monthly bills; but it appears that, because of the good cheer which Mr. Smalley purveyed, from a quarter to a third of the recipients looked forward to them as affording a bright spot in the month. The "fan mail" was not always laudatory; indeed one suspects that if it had been Mr. Smalley would have doubted he was making good. Some of the letters were caustic, of course, since it is impossible always to please everyone. Others demanded further and more complete explanation of what had been misunderstood. But the great bulk of them were appreciative and usually expressed sincere thanks for the friendly word which Mr. Smalley had provided. But never to Mr. Smalley, as such! His anonymity was complete.

Only one of the appreciative letters thus received was ever published. It came from Margaret Deland, the novelist, when "Between Ourselves" was a comparatively new thing. In part she said: "Your little leaflet, 'Between Ourselves' for July 1924 is so extremely well done that I cannot help congratulating you upon having in your service any person who can write advertisements with such vigor, logic and literary charm." But there were many others of similar import, notably from college and other teachers, frequently requesting additional copies of the leaflet for use in class work because of its distinctive literary style.

"B." Smalley, as he is always known to his friends, was never one to seek the spotlight. He was born in Lebanon, N. H., October ag, 1871 and entered Dartmouth with '94 in the fall of 1890. Even then he was an unsung hero—one of those who toiled faithfully and nursed the bruises of conflict received in giving the Varsity eleven something adequate to work on by way of home training. He took no credit for the fact that in those remote days the second string players were often more successful in carrying out their assignments than were the Varsity team; yet the credit was due. Incidentally, "B." was a high-ranking student; and among his interests were the opportunities which the College afforded in a literary way, which led to his identifying himself with the Literary Monthly then flourishing.

On emerging from college, Mr. Smalley adopted the not unusual course, then and since, of selling life insurance while he cast about for other work to do. This period was brief, for writing called him and he became a reporter on the BostonDaily Advertiser and Boston Evening Record. From these lively publications, now mere memories save as transmogrified by Mr. Hearst, he went in 1899 to the editorial staff of the Boston Transcript. It was not until 1906 that he discovered his outstanding gifts as an advertising genius; and in that year he withdrew from newspaper work to become advertising manager for Rueter & Company, and the A. J. Houghton Company of Boston. Here he began to reveal the talents for alluring publicity matter which were destined to flower forth in "Between Ourselves." He was called to become assistant publicity manager for the New England Telephone Company early in 1923, and in September of that year was named publicity manager. In a way it was a return to an early association; for in his younger days, from 1886 to 1888, he had served as a night telephone operator in Lebanon and in Greenfield, Mass.

No MORE ANONYMITY

If the New England Telephone & Telegraph Company has enjoyed an unusually cordial relationship with its public as it has—it is in no small part due to Bert Smalley's geniality and common sense as radiated through his brief monthly published chats with the company's clientele. To his friends and to this MAGAZINE it seems that the time has come for him to emerge briefly from his persistent anonymity and take a bow. An infinitude of good work is done every day in the year by writers whose names the world never hears, and who boast not even a nom de plume for their identification. High in the ranks of such workers was "B." Smalley, meriting acclaim but never seeking it, and indeed modestly avoiding it. With presumably many years of potential activity ahead of him, it seems a pity that the arbitrary provisions of a pension system should call a halt; but surely there are still avenues open to one who wields so vigorous and so persuasive a pen.

The gift of penning many words, subject to a hard and fast schedule, without becoming commonplace and without boring the reader, is not too widely vouchsafed to mankind—but if ever it were bestowed on any one it was on Bert Smalley. What he was called on to do, he did well none could have done it better; and the cessation of his regular output of good cheer could not be otherwise than greatly missed. That all Dartmouth men should share in the appreciation of a useful man, hitherto known by few aside the circle of his intimate associates in business, is the sentiment which prompts this attempt to do him justice. There are plenty of "institutional" writers in the land, but few who rise to the heights by Mr. Smalley reached and kept.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleEat the Cake and Have It Too

November 1936 By WILLIAM J. MINSCH '07 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1911

November 1936 By G. Burleigh -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1934

November 1936 By Martin J. Dwyer Jr -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1918

November 1936 By Allan C. Gottschaldt -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1921

November 1936 By Paul C. Belknap -

Sports

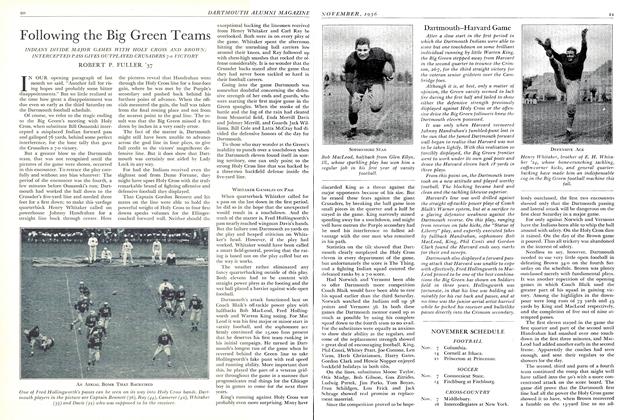

SportsFollowing the Big Green Teams

November 1936 By ROBERT P. FULLER '37

PHILIP S. MARDEN '94

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLETTERS TO THE EDITOR

December 1932 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters

June 1939 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters

July 1947 -

Article

ArticleREPORT OF THE COMMITTEE ON ALUMNI PROJECTS

AUGUST 1930 By PHILIP S. MARDEN '94 -

Article

ArticleA Class Chairman's View

November 1952 By PHILIP S. MARDEN '94 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1894 Enjoys Its 60th

July 1954 By PHILIP S. MARDEN '94