WE brought nothing into this world and it is equally certain we shall take nothing out of it, but many of us will accumulate varying amounts of goods and chattels which we may enjoy while we are here; and when we depart it is possible for us to direct how they shall be distributed among those who remain.

Speaking generally, a man is free to do as he likes with his own, so long as he does not injure another. There are, to be sure, certain restrictions on the making of wills, but these are not likely to bother us much. Even though he may not greatly like his wife, a husband may not deprive her of her dower rights in his estate; and there is a thing called the "rule against perpetuities" designed to prevent tying up estates for excessive lengths of time. But otherwise one is free to distribute his worldly goods in such ways as he sees fit, both to benefit the living and to mitigate the tax burdens upon them, keeping strictly within the law.

Making a last will and testament is naturally a solemn business, and with many it is so very solemn that it is deliberately postponed often too long, in which case the state steps in and directs the process of distribution. But for such as can take a less somber view of things, will-making soon loses its excessive awesomeness, especially for such as prudently keep their testamentary arrangements up to date by frequent revision to fit the changes of circumstance as life goes on. One does well to face it, not putting off for tomorrow what would much better be done today. If a word of advice be not amiss, make a will early, and renew or amend it from time to time as seems desirable, under competent legal advice, because you naturally wish your will to be effective.

As a rule, testators make a first concern the insurance of the security of their immediate families, so far as may be possible in this uncertain world. But after that, especially if life has been kind, arises in most of us a wish to benefit others, above and beyond the call of duty. This may be due, in part, to an understandable desire for self-memorialization. Much more often, however, it springs from an honest desire to be of service to the world one is leaving behind, continuing the good one strove to do while still living.

In a world constituted as ours is, capacities to render such posthumous service vary greatly; but the main purpose of this writing is to combat the notion that testamentary benefaction is something possible only to the very rich. It is true that only such as have very great possessions can make the vast gifts that make the headlines - set up monumental "Foundations," endow professorships, or erect laboratory buildings to bear their names for an age, or for ajl time. But it does not follow that the multitude of us, who have much more modest fortunes, can do nothing. The fact is, we can do a great deal and should. One thousand people, each giving a thousand dollars which is a modest individual contribution, as such things go do as much, in the aggregate, as does the one man who gives a million. There is virtue in the idea that many a mickle makes a muckle.

These smaller bequests, inconsiderable as they may look to us when contrasted with the mammoth gifts of the very rich, are exceedingly important and are highly appreciated. Those who have been at pains to investigate the single case of Dartmouth College report that the aggregate of smaller bequests through the years approaches more closely than one realizes the aggregate of the dozen or so of gifts of outstanding magnitude. That was done without any organized effort to stimulate the smaller bequest; and that has inspired the idea that, if a greater effort were made to awaken alumni and other friends of Dartmouth to the existing opportunity, it should prove of very substantial benefit to the College. It is in support of this movement that this article is written.

The idea is to remind the reader of the importance of a multitude of bequests, none of great size when compared with the big gifts which only a very few are in position to make, and to increase the volume thereof year by year, as an important support for the financial structure of the College.

There are many ways of carrying out this project. The simplest is to include in one's will a paragraph bequeathing to Dartmouth College an outright sum of money, free to be used for any purpose in the discretion of the Trustees, or directed to some special use which the testator has in mind such as scholarships, faculty salaries, or the continuance of one's contribution to the Alumni Fund. Probably the most widely useful bequest is the unrestricted one, but all are most welcome and will be highly appreciated. The same result may be achieved by the use of in- surance.

Bequests may also be made effective while the testator is still living, by making an immediate gift subject to a life income agreement or an annuity for the duration of one or two lives. Gifts by will or other- wise may be made by turning over securities, which one might be reluctant to sell because of the tax on capital gains. In all cases the financial officers of the College stand ready to advise intending testators concerning methods and tax aspects, and may be freely consulted on matters of detail.

PHILIP S. MARDEN '94 of Lowell, Mass., former Alumni Trustee, is bequest chairman for his class.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleOn Educational Policy

November 1952 By PROF. ANTON A. RAVEN -

Article

ArticleThe Business of Being a Gentleman

November 1952 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

November 1952 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR -

Class Notes

Class Notes1929

November 1952 By F. WILLIAM ANDRES, EDWIN C. CHINLUND -

Article

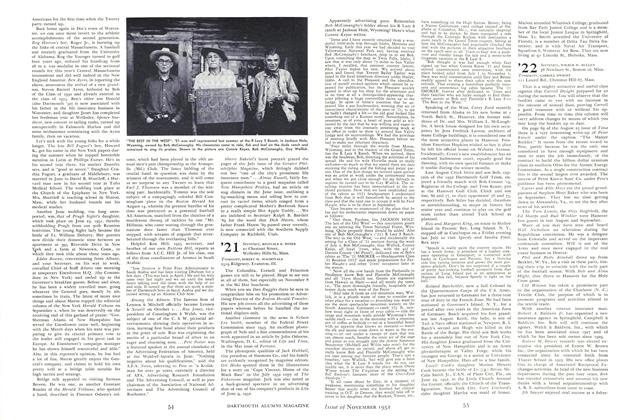

Article"The Greatest Sport"

November 1952 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1921

November 1952 By REGINALD B. MINER, ROBERT M. MACDONALD

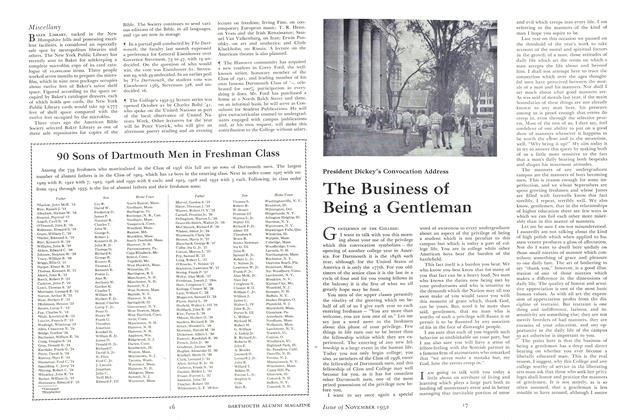

PHILIP S. MARDEN '94

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters

June 1939 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters

July 1947 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters

February 1951 -

Article

ArticleREPORT OF THE COMMITTEE ON ALUMNI PROJECTS

AUGUST 1930 By PHILIP S. MARDEN '94 -

Article

ArticleRevealing an Anonymous Author

November 1936 By PHILIP S. MARDEN '94 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1894 Enjoys Its 60th

July 1954 By PHILIP S. MARDEN '94