HISTORY OF THE FAMOUS TREES THAT GRACE THE STREETS ANDCAMPUS; THE THREAT OF DISEASE AND DEATH

THE STREETS of Hanover are lined by hundreds of elm trees. They overtop most of the older residences and canopy the College buildings and grounds. Their presence in every season and for all college functions has impressed them in the memories of many Dartmouth generations. Even before Baker displaced Butterfield at the end of an enlarged central campus, the graceful shadows of architects' elms fell against the walls of the projected library. More shadows on architects' drawings of the hoped-for Student Union and the new dining halls foretell future elms to unify the new structures with the old. Beautiful trees—rows of arching elms, their bare branches silhouetted against the frosty white of Dartmouth Row, their dense foliage throwing great shadows on the campus—how closely these things are woven into the pattern of what Hanover means to Dartmouth men.

Coming generations will probably enjoy in Hanover the same atmosphere of combined shelter and freedom that only elms can give. But changes and losses in our tree population are inevitable, particularly during the years just ahead. Gaps in the rows about the Green and within sight of it will appear and be more noticeable because the canopy of branches has been so tall and even. The burning of the White Church in 1931 destroyed one unreplaceable elm with 92 rings, most of them wide and indicative of better conditions for growth in the past than can be provided again on that busy corner. This loss was due to accident but the recent removal of a tree killed by natural forces in front of Silsby, opposite Carpenter Hall, has come as a reminder that its death, along with that of several others about town, is the beginning of the end of its generation.

MUCH TREATED TREE

The elm just cut stood for years in front of Prof. Henry Parker's house, later occupied by the Tri-Kap .fraternity. Like other large ones near the Green, it had been treated, braced and patched for years but 11 was probably older and certainly larger. It reached a trunk diameter of nearly 5 feet at breast height, flaring to 6½ feet at the ground where it encroached on sidewalk and street. Cut with much labor, the sound part of its stump shows its age to have been 112 years. The rings for the first 50 years were very wide but even in recent years the trunk enlarged its diameter by at least half an inch each year. This same speed of growth has been shown in the other stumps of elms lost in other parts of the village. The proof that elms are not slow growers and not particularly long lived appears to have surprised visitors. Elms really increase in diameter about as fast as white pine and much faster than maples and oaks. Even seedlings soon come to be useful trees so we must expect great changes in them later. Eventually they die in spite of surgery and treatment which are no more permanently effective on trees than on human patients.

ORIGINALLY ALL PINES

The prospect of loss of our oldest campus trees turns our thoughts back a century and a half; how did the smaller college and smaller village appear then? It is certain that all the elms were planted or developed from natural seeding for the original forest was a pure stand of white pine. Its descendants have retained control in Pine Park and the old cemetery while numerous stumps of the original pine trees stood on the rough green as late as 1830. Each class of the period just before 1820 was expected to pull one stump as their contribution to the clearing of the center campus. According to their own records, the Trustees in 1808 voted to improve this tract, then split diagonally by the highway from southwest to northeast, by suitable grading, seeding, fencing and tree planting "provided the same can be effected without expense to the Corporation." The Trustees attacked the problem again in 1831 but it was not until 1836 that the work could be financed by joint action of the College and local citizens. However, there is no proof that trees were actually planted as a part of this project. Natural seeding by wind-borne elm seeds has never produced a tree on the green, perhaps because the town cows were allowed to graze there even after the fence was erected.

If the 112-year elm just cut on North Main St. was several years old when planted there, it is evident that it and many other trees of about that age along Main and College streets were set out as saplings at about this time, probably a few years earlier. Pictures of these streets taken about iB6O show the presence of a few still older elms, now gone but evidence of tree planting as one of the first acts of the founders of the village. There seem to be no written records of any of these early provisions for shaded streets but the old photographs show that maples were also used though with less satisfactory results.

The first elms for which we know the date of planting and the person responsible were placed around the campus in 1844, apparently through the efforts of Dr. John Richards, pastor of the College Church from 1842 to 1859. He was actively interested in trees and at one time had a small nursery from which he distributed young trees about the village. What must have been his first work with elms was done along Main, Wentworth and College Streets, including some trees placed in front of his church. A check on the date of these plantings was obtained from the 92 rings in the stump of the elm already mentioned as killed by the White Church fire. That particular sapling was 5 years old when transplanted there. Trees of the same lot appear at various points about the green in photographs of about 1865 and in all recent views.

The connection of Dr. Richards' planting with the work of the "Hanover Ornamental Tree Association" is not clear and it may have been identical. This organization is said to have been formed in 1843 and ceased to function after its work of 1844. From our knowledge of its nature when revived later, it is very likely that Dr. Richards was the most active part of it.

Although good steel engravings of the 1850's indicate wooden guards about very small trees at the northwest corner of the campus, the next positive record of elm planting attributes a long row of trees to the personal efforts of Professor John E. Sinclair, teacher of mathematics 1863-69. These were elms planted along the north side of East Wheelock St., opposite the present Gymnasium. In the words of an eye witness to a part of the work, "I remember very well meeting Professor Sinclair one morning with a pair of rubber boots on, with a sapling, which is no doubt now one of those great trees, over his shoulder." Since Professor Sinclair built and occupied the then isolated house at 15 East Wheelock St., it seems that he sought to alleviate the barrenness of what was then an undeveloped section. Photographs in the class albums of 1867 and 1869 show that side of the street both without and with the young elm saplings before his house. However, it should be observed that he did more than set trees in front of his own home, the usual practice of recent times.

From many photographs taken in the 1860's and later, we have a good record of Hanover's steady growth in size with a corresponding improvement in the ap- pearance of its barren fringes. In addition to pictorial proof of scattered plantings about the central portion, West Wheelock Street was among the first of the new areas to be given elms, largely because its naked banks and gullies provided a dreary sight for incoming students, visitors and all travelers arriving by way of the railroad station. In the early seventies a planting of 4.0 elms was made along the south side of this entrance, then called River Hill. Again a citizen provided them for the total expense of the work was met by Dr. William T. Smith, son of President Smith and later physician in Hanover. He hired two men "to bring in the trees on their backs from the sides of the railroad below Blood Brook."

Later in the seventies, the Tree Association of 1844 was reformed with the name changed to Village Improvement Society although its main purpose was to care for old trees and to plant new ones. President Smith was its first president and Professor Frank Sherman was its last (1900) but everyone agrees that Deacon Downing really planted the elms with the financial support of the group. He maintained a nursery on a plot along Maple Street, south of the now vacated high school building. From it he moved hundreds of trees to the village streets, interspaced between the older elms and maples or set in larger numbers along the streets in the new residential districts. For a specific reference to this work, we read in TheDartmouth for June 24, 189.5: "Between one and two hundred trees have been set out in town this season by the Village Improvement Society."

With tree wardens officially a part of the precinct government since 1901, the planting of new trees has ceased to be the responsibility of private citizens although the work still requires the personal attention of interested persons. For example, when Dr. H. N. Kingsford acted as a precinct commissioner in setting 352 elms about the village in 1911, only part of the work was done at the expense of the taxpayers. With the volunteer assistance of a few students and at some expense to himself, Dr. Kingsford continued the work after his precinct budget was exhausted. A. P. Fairfield was another village official who added young elms on North Park Street where the late Dean Emerson had started some years earlier.

Tree planting on the College grounds and particularly about its new buildings has been in the hands of College authorities for the last 60 years at least but the most interesting of these additions are the "class trees." Sponsored and planted by the Seniors of most classes from 1868 to about 1892, they are cherished for their origins but far outnumbered by the work of professional agencies. Most of the class trees were elms and they were often placed close by College buildings. For example. The Dartmouth for May 16, 1879 carried the following: "The '79 class tree has been set out in the triangular plot between Thornton and Reed. Carl has it under his fostering care." The species of tree in this case is disclosed by another item: "The Seniors gave their class tree a send off, last Wednesday evening, with a sing and a lemonade shout to the College, under the boughs of that youthful elm." The tree is still alive and may be identified by the iron marker at its base.

Either through good judgment or for reasons which required less thought, some of the classes decided to claim a living tree. 'B4 was one of these for they "adopted" a tree in the park instead of trying to plant one"as is usually the case." The wisdom of thus obtaining a living token is supported by accounts in the monthly Dartmouth issues for May and June of 1870: "The Seniors have voted to set out two class trees in front of the Gymnasium" (then Bissell Hall). The second news item began, "The Seniors planted their class trees June Ist—two elms, on the east side of the gymnasium." Among the toasts of the occasion was one "Root tree or die" by John E. Pike. The account closed with, "The trees unhesitatingly accepted the latter alternative."

PLANTED ABOUT 1777

With so many huge elms about the campus and village, many persons have asked or wondered which is the oldest of all. Although it is impossible to be accurate in estimating the ages of such large trees as those in front of Robinson Hall, Crosby, Clark School, the S A E house ancl the spreading one on Elm St. opposite the Dragons' new site, there is no question but that the elm near Rollins Chapel is the oldest tree in town. Its closest rival for the honor seems to be the unusual elm beside Bartlett Hall but the latter is at least 30 years younger. Both are famous and have a national reputation, being listed with historic trees of national interest.

To begin with the junior one, the Bartlett elm attracts much attention through the curious forms assumed by its principal branches. The upper ones have grown in first one direction and then another with the abrupt downward turns most responsible for the odd appearance of the tree as a whole. The drooping lower limb has long hung so close to the terrace that the children of several Hanover generations have swung from it without injury to the tree or themselves. The death of all twigs on a smaller branch caused its removal from a point about go feet from the ground and from this we have obtained a close estimate of the tree's age. The branch showed 108 rings, making the tree about 130 years old now. This confirms prophecies made for it during the late 19th century when the trunk was much used as a target for rifle practice. It was often said, "The wood In that tree will never rot—it's too full of lead." Unfortunately the life of a tree depends also upon its bark and an obscure fungus has already so weakened this tree that it cannot live much longer.

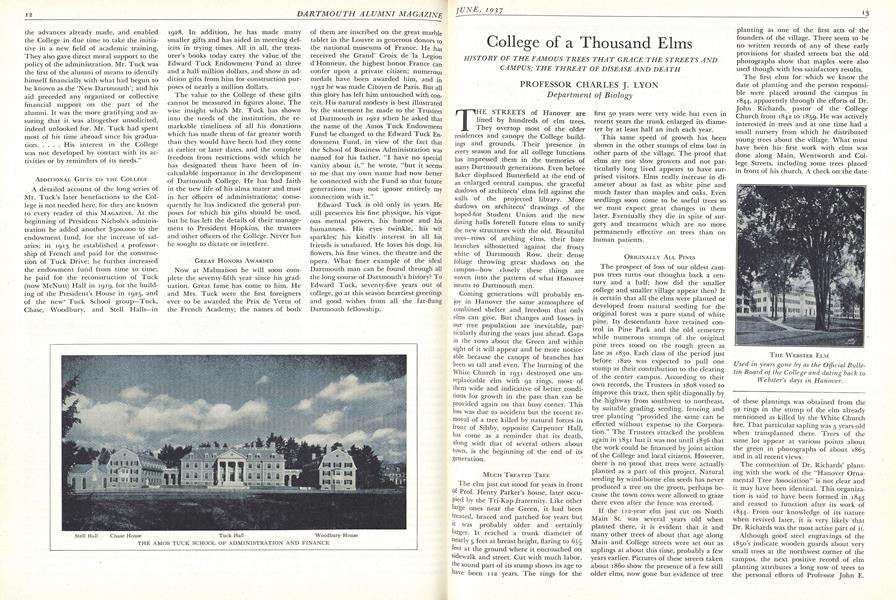

The rings of our oldest elm have never been counted but we know from old photographs and from personal anecdotes that it must be 160 years of age or older. The earliest photograph in the College archives shows it clearly as an unusually large elm then (about 1850). All living Dartmouth men remember it as a huge tree, forked low into a vase-like group of branches and growing on the Wentworth Hall side of the junction of Wentworth and College Streets. For all who met daily in Rollins Chapel it stands for the oldtime College bulletin board, with its bark full of the nails of posters and official announcements. To-day it is an aged but vigorous veteran, scarred by filling in its central cavity and braced against the strains of storms. In some way the name Webster Elm has been given to it. It is almost as old as the College.

The oldest and longest inhabitants of Hanover remember this elm as a very old tree with a hollow trunk as far back as 1870. According to the excellent memory of Dr. G. D. Frost, physician and untiring student of Hanover genealogy, the cavity was so large in 1872 that he and his playmates of 8 to 12 years of age could enter it freely as they played about it.

For earlier portraits of this tree we must look at reliable steel engravings of that section of the campus. The very oldest views of the 19th century are obviously adorned with walks, trees and shrubs that never existed, with no pretense of accuracy even in the buildings. The first one to appear trustworthy is dated 1851 and it shows our familiar Webster Elm in the foreground, very large and unmistakable. By chance we have another anecdote of the tree in that period, confirming the idea that it was then already full-grown. Professor Charles A. Young, born on the west side of the Green in 1834, grew up in Hanover. As a colleague and friend of Dean Emerson he often spoke of his boyhood days and the Dartmouth that he first knew. Through Mrs. Emerson we learn that Professor Young knew the great elm well and as a small boy liked to climb into the nest formed by the many large branches.

LEGEND OF WEBSTER ELM

There may be other early records of this elm but the present evidence points to it as one of the first hardwood trees to have been planted on the campus. There is a legend—no more—that it was originally a group of trees set out and bound together until their trunks fused as one. The truth of this vague story will be revealed in the ring pattern of the stumps when the best care and protection available can no longer save it.

The nature and extent of the present efforts of the College and village to care for its old trees and to provide even more for the future, deserve much praise. The constant attention of trained men and expert consultants is used and needed in the struggle against diseases, drouths, mechanical forces and the injurious effects of paved surfaces around many of them.

The question in all our minds is the fate of the elms if the Dutch elm disease cannot be eradicated. It is still too early to be certain but there is now some cause for hope that its spread will be prevented. The elm bark beetle that carries the fungus from tree to tree in Europe has not been found in America. If another carrier appears here it may very well be limited in its natural range by the cold winters of northern New England and many other parts of the elm range. There are many climatic differences between Europe and the home of the American elm.

The immediate danger to Hanover's elms lies in other fungus infections, particularly the "shoestring rot" of the bark. Infections of this and other parasites spread in the inner bark for months before their presence is made known. Removal of infected tissues is effective unless the tree has been girdled or so weakened that it dies. The danger is greatest for the older trees and nothing but expert service has preserved them. The dark scars of tree surgery are unsightly but very necessary.

The annual measurement and check of each tree near College property is an important part of the plan for systematic care. In recent years special fertilizers have been supplied to the roots of trees growing in unfavorable locations, with much benefit to the general vigor of the old elms in particular. The annual pruning of dead branches is not as purposeless as it may appear to some; the fungus tissues must be removed from the tree or they will invade living branches.

The planting of more trees, particularly on new developments of the College properties, is still in progress although the immediate needs have been largely satisfied. Mr. Gooding estimates that nearly 150 trees, chiefly elms, have been successfully transplanted to the campus during the past 10 years. Dozens of others have been set in college-owned residential areas, such as Valley Road and South Balch Street. The precinct officials have also been active. The results of these and all former plantings throughout the village are widely and favorably known.

THE WEBSTER ELM Used in years gone by as the Official Bulletin Board of the College and dating back toWebster's days in Hanover.

THE FAMOUS BARTLETT ELM STANDS NEXT TO BARTLETT HALL, NOTED FOR ITS GRANDEUR AND PECULIAR FORMATION OF LOWER LIMBS

AUTHOR OF THIS ARTICLECharles J. Lyon, Professor of Botany,studying the rings from a tree trunk inSilsby laboratory

VALLEY ROAD LANDSCAPING Sizeable young elms are used in new developments such as this one east of MemorialField, bordering on Chase Field.

ULMUS CAMPESTRIS Year-round care by a crew of tree surgeons(one shown at work above) maintains thehealth of hundreds of Hanover elms.

Department of Biology

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleMr. Tuck 75 Years After Graduation

June 1937 By FRANCIS LANE CHILDS '06 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1927

June 1937 By Doane Arnold -

Article

ArticleHow Does the College Change?

June 1937 By ROBERT DAVIS '03 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1931

June 1937 By Edward D. Gruen -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1936

June 1937 By Richard F. Treadway -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1910

June 1937 By Harold P. Hinman