A PLEASANT LETTER from Craig Thorn '31 requests that I review, now and then, some "old established books or "old books not so well established" but in my opinion worthy. This I shall be only too glad to do, beginning with this issue.

A recent book by Henry David Thoreau, called Men of Concord, edited by F. H. Allen, and handsomely illustrated by N. C. Wyeth, may be a good starting point for the mention of some excellent old books. This book, drawn entirely from Thoreau's Journals which, at his death, ran to thirty manuscript volumes, deals with characters in and about Concord. The book, together with the illustrations, distill for the reader the very essence of New England.

Thoreau was not without humor as witness his remark, "Some circumstantial evidence is very strong, as when you find a trout in the milk." He was also a poet as when he wrote, "The blue bird carries the sky on his back." Lovers of Thoreau find pleasure in some of his poetry notably in "Smoke," 1843, and "Inspiration" published In 1863.

Have we forgotten two of his books which will forever be American classics? His first book A Week on the Concord andMerrimack Rivers is a description and narrative of a boating trip that he and his brother John took in August and September, 1839, when Thoreau was just twentytwo. He had been two years out of Harvard. The book is full of minute observations of nature, and it is also an excursion into transcendental philosophy. One thousand copies were printed andseven hundred and six were returned to Thoreau by the publisher as unsold, whereupon Thoreau wrote in his journal: "I have now a library of nearly nine hundred volumes, over seven hundred of which I wrote myself."

His second great book published during his lifetime, is, of course his Walden, issued in 1854. Thoreau had wished to make living a fine art, and as he believed that man had lost his independence (long before the New Deal), he wanted to prove to himself at least that he could live, independently and happily, a life of "plain living and high thinking." So he built his hut at Walden Pond on a piece of land that Emerson loaned him for the purpose. The result of this great experiment he incorporated in his book, one of the half dozen great American classics.

To these two books should be added his famous Essay on Civil Disobedience, which may be found in the late Professor James MacKaye's selections from Thoreau's writings entitled Thoreau: Philosopher ofFreedom. This is an excellent book, and the introduction reveals not only Thoreau, but Mr. MacKaye as well, who was a true Thoreauvian.

Only one more book need be added to have a fairly adequate Thoreau collection and that is Odell Shepard's The Heart ofThoreau's Journals.

Mr. Townsend Scudder has recently published a book about Thoreau's great friend and mentor Ralph Waldo Emerson, entitled The Lonely Wayfaring Man, which treats of Emerson's three trips to England and his relationships there with Thomas Carlyle, Crabb Robinson, Wordsworth, Landor, and William Allingham. A competent and interesting book.

Alan Hewitt, who wrote so entertainingly of the show business in the December issue, corrected a blatant error of mine when I attributed The Green Pastures to Maxwell Anderson. It should have been, of course, Marc Connelly. I wish I had space to quote his entire letter but I note that he has been reading Shakespeare, Shaw's new plays, Jane Eyre, Oscar Wilde Discovers America,Memoirs of Sacha Guitry, Ibsen, the Letters of D. H. Lawrence, Leaves of Grass,Tovaritch, and Maxwell Anderson's TheWingless Victory, which Alan believes "is the finest thing he has yet done and a great play to boot."

A beautifully printed book from the University of Minnesota Press has recently appeared entitled Tales of the Northwest by William Joseph Snelling. This is a reprint of an early Western classic. The tales are of the Dahcotas, the Sioux, and the Saques and Foxes, and all reveal the life and character of these Indians. I shall be surprised if this volume is not picked as one of the fifty best printed books of the year.

Another book on air fighting has appeared in England, which is one of the best that I have read. It is called FighterPilot, by one who calls himself "Mc Scotch," who served with the R. F. C. with the greatest of British aces "Mick" Mannock, V.C. D.S.O. M.C., etc. Well illustrated and entertainingly written.

J. Lewis May in his book John Lane andthe Nineties writes from first hand knowledge of Lane and The Yellow Book, Aubrey Beardsley, Wilde, John Davidson, Richard Le Gallienne, and others. The age comes to life and the book may safely be recommended to those who enjoy literary histories.

A. E. Housman's death deprived us of a major poet. A friend of long standing, Andrew S. F. Gow, has written a brief memoir, done with great restraint, entitled A. E.Housman: A sketch together with a list of his writings and indexes to his classical papers. This was published by the Cambridge University Press.

Whiskey and Scotland, by Neil Gunn. Routledge, 1935.

Anyone who likes good Scotch whiskey will enjoy this book, as will those who don't like it. Most of the people who drink it, know little about what it is made of, or of how it is made, or know what pot-still whiskey is, or even know one blend from another save for well-advertised trade names. If you are of any of these groups you will find here not only an essay on whiskey in relation to Scotland's history and politics, but also a fine exposition of how whiskey is made, of the extreme skill required in distilling a really fine whiskey, and what the best whiskies are. It is safe to assume that very few Americans have ever had really fine Scotch whiskey. As this is equally true of Scotsmen and Englishmen, the mystery is an intriguing one, and Mr. Gunn, one of the best of the younger crowd of Scottish writers, along with Eric Linklater, George Blake, and others, explains it here with considerable acumen and charm.

We Did Not Fight, 1914-1918, by various hands. Faber, 1936.

This book, introduced by Canon Shephard, of St. Martin-in-the-Fields, London, contains various chapters by several war resisters in the last war, giving their experiences. One learns from the introduction that the 1600 conscientious objectors in the war have grown to the twelve million peace voters of 1935. The pacifists, who are realists, must know that they haven't much to stand on, but if you have any sympathy with this point of view the book should interest you.

The books of this past year which, I think, may be safely recommended are as follows:

The Last Puritan, by George Santayana. Scribners. Previously reviewed in these columns (just a year ago).

From, a Surgeon's Journal, by Harvey Cushing. Little, Brown. An intelligent one man's view of the war.

G. K. Chesterton's Autobiography. Sheed and Ward. Rather more impersonal than an autobiography should be, but the author was unable to write a bad book.

The General, by C. S. Forester. One of the most neglected good books of the year.

Arctic Adventure, by Peter Freuchen. Farrar and Rinehart.

Education before Verdun, by Arnold Zweig. Viking.

The American Language, by H. L. Mencken. Knopf. The fourth edition of a very amusing and instructive book.

John Nicol: Mariner, edited by Alexander Laing. Farrar and Rinehart.

Audubon, by Constance Rourke. Harcourt Brace.

Life of Robert E. Lee, by Douglas Freeman. Scribners.

A Further Range, by Robert Frost. Holt.

Murder in the Cathedral, by T. S. Eliot. Harcourt.

Rodeo, by R. B. Cunninghame Graham. Doubleday, Doran. If you don't like these stories I shall consider myself baffled.

War Memoirs of David Lloyd George, in five volumes. Little, Brown.

The Country Kitchen, by Delia Lutes. Little, Brown.

More Poems, by A. E. Housman. Knopf. Gallipoli, by John North. Harcourt. Bos-well's Journal of a Tour to theHebrides. Viking.

The Flowering of New England, by Van Wyck Brooks. Dutton.

The People, Yes, by Carl Sandburg. Harcourt.

Quack! Quack! by Leonard Wolff. Harcourt.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleGradus Ad Parnassum

February 1937 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1911

February 1937 By Nathaniel G. Burleigh -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1936

February 1937 By Rochard F. Treadway -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1929

February 1937 By F. William Andres -

Article

ArticleThe Modern Museum

February 1937 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1927

February 1937 By Doane Arnold

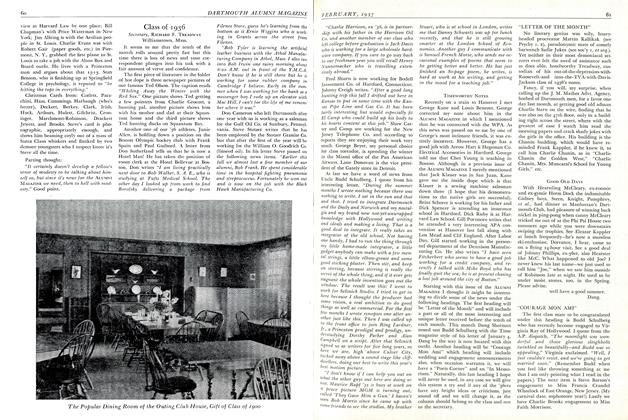

HERBERT F. WEST '22

-

Article

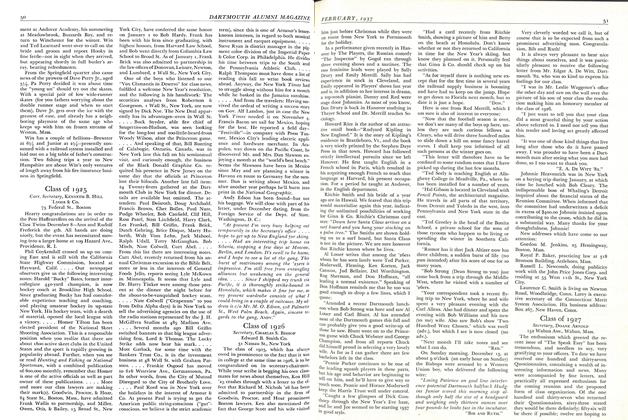

ArticleHanover Browsing

November 1937 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

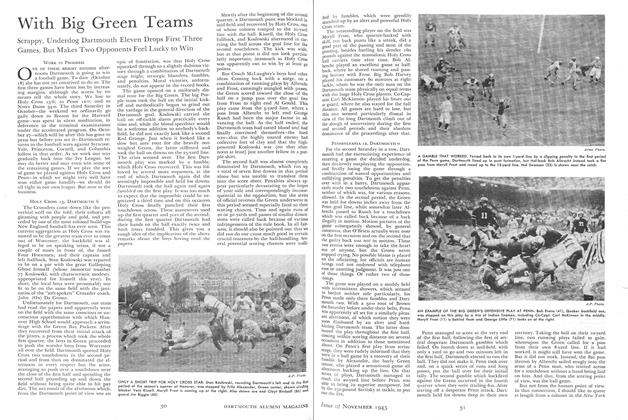

March 1939 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

October 1941 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

November 1945 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

March 1946 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

February 1953 By HERBERT F. WEST '22