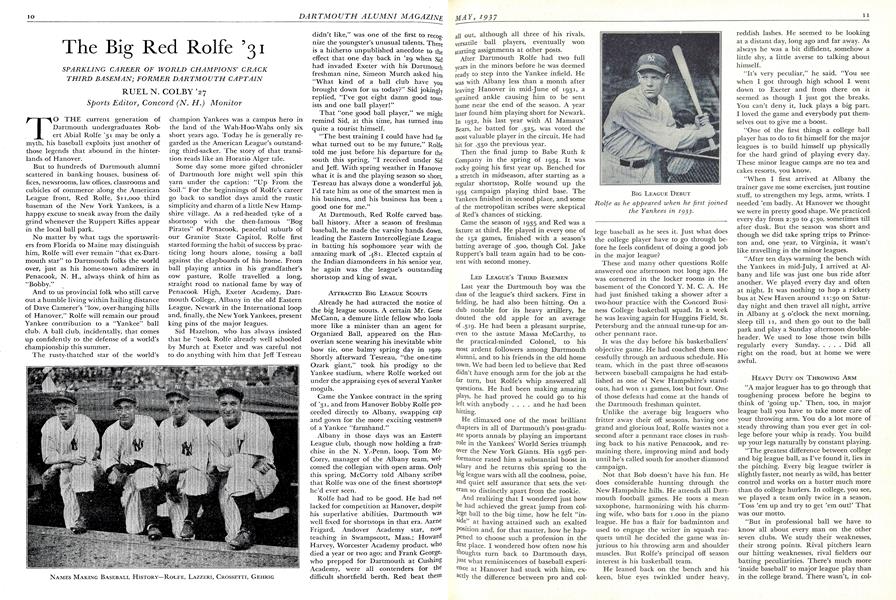

SPARKLING CAREER OF WORLD CHAMPIONS' CRACKTHIRD BASEMAN; FORMER DARTMOUTH CAPTAIN

TO THE current generation of Dartmouth undergraduates Robert Abial Rolfe '31 may be only a myth, his baseball exploits just another of those legends that abound in the hinter- lands of Hanover.

But to hundreds of Dartmouth alumni scattered in banking houses, business offices, newsrooms, law offices, classrooms and cubicles of commerce along the American League front, Red Rolfe, $11,000 third baseman of the New York Yankees, is a happy excuse to sneak away from the daily grind whenever the Ruppert Rifles appear in the local ball park.

No matter by what tags the sportswriters from Florida to Maine may distinguish him, Rolfe will ever remain "that ex-Dartmouth star" to Dartmouth folks the world over, just as his home-town admirers in Penacook, N. H., always think of him as "Bobby."

And to us provincial folk who still carve out a humble living within hailing distance of Dave Camerer's "low, over-hanging hills of Hanover," Rolfe will remain our proud Yankee contribution to a "Yankee" ball club. A ball club, incidentally, that comes up confidently to the defense of a world's championship this summer.

The rusty-thatched star of the world's champion Yankees was a campus hero in the land of the Wah-Hoo-Wahs only six short years ago. Today he is generally regarded as the American League's outstanding third-sacker. The story of that transition reads like an Horatio Alger tale.

Some day some more gifted chronicler of Dartmouth lore might well spin this yarn under the caption: "Up From the Soil." For the beginnings of Rolfe's career go back to sandlot days amid the rustic simplicity and charm of a little New Hampshire village. As a red-headed tyke of a shortstop with the then-famous "Bog Pirates" of Penacook, peaceful suburb of our Granite State Capitol, Rolfe first started forming the habit of success by practicing long hours alone, tossing a ball against the clapboards of his home. From ball playing antics in his grandfather's cow pasture, Rolfe travelled a long, straight road to national fame by way of Penacook High, Exeter Academy, Dartmouth College, Albany in the old Eastern League, Newark in the International loop and, finally, the New York Yankees, present king pins of the major leagues.

Sid Hazelton, who has always insisted that he "took Rolfe already well schooled by Murch at Exeter and was careful not to do anything with him that Jeff Tesreau didn't like," was one of the first to recognize the youngster's unusual talents. There is a hitherto unpublished anecdote to the effect that one day back in '29 when Sid had invaded Exeter with his Dartmouth freshman nine, Simeon Murch asked him "What kind of a ball club have you brought down for us today?" Sid jokingly replied, "I've got eight damn good tourists and one ball player!"

That "one good ball player," we might remind Sid, at this time, has turned into quite a tourist himself.

"The best training I could have had for what turned out to be my future," Rolfe told me just before his departure for the south this spring, "I received under Sid and Jeff. With spring weather in Hanover what it is and the playing season so short, Tesreau has always done a wonderful job. I'd rate him as one of the smartest men in his business, and his business has been a good one for me."

At Dartmouth, Red Rolfe carved baseball history. After a season of freshman baseball, he made the varsity hands down, leading the Eastern Intercollegiate League in batting his sophomore year with the amazing mark of .481. Elected captain of the Indian diamondeers in his senior year, he again was the league's outstanding shortstop and king of swat.

ATTRACTED BIG LEAGUE SCOUTS

Already he had attracted the notice of the big league scouts. A certain Mr. Gene McCann, a demure little fellow who lo.oks more like a minister than an agent for Organized Ball, appeared on the Hanoverian scene wearing his inevitable white bow tie, one balmy spring day in 1929Shortly afterward Tesreau, "the one-time Ozark giant," took his prodigy to the Yankee stadium, where Rolfe worked out under the appraising eyes of several Yankee moguls.

Came the Yankee contract in the spring of '31, and from Hanover Bobby Rolfe proceeded directly to Albany, swapping cap and gown for the more exciting vestments of a Yankee "farmhand."

Albany in those days was an Eastern League club, though now holding a franchise in the N. Y.-Penn. loop. Tom McCorry, manager of the Albany team, welcomed the collegian with open arms. Only this spring, McCorry told Albany scribes that Rolfe was one of the finest shortstops he'd ever seen.

Rolfe had had to be good. He had not lacked for competition at Hanover, despite his superlative abilities. Dartmouth was well fixed for shortstops in that era. Aarne Frigard, Andover Academy star, now teaching in Swampscott, Mass.; Howard Harvey, Worcester Academy product, who died a year or two ago; and Frank George, who prepped for Dartmouth at Cushing Academy, were all contenders for the difficult shortfield berth. Red beat them all out, although all three of his rivals, versatile ball players, eventually won starting assignments at other posts.

After Dartmouth Rolfe had two full years in the minors before he was deemed ready to step into the Yankee infield. He was with Albany less than a month after leaving Hanover in mid-June of 1931, a sprained ankle causing him to be sent home near the end of the season. A year later found him playing short for Newark. In 1932, his last year with Al Mamaux' Bears, he batted for .325, was voted the most valuable player in the circuit. He had hit for .330 the previous year.

Then the final jump to Babe Ruth & Company in the spring of 1934. It was rocky going his first year up. Benched for a stretch in midseason, after starting as a regular shortstop, Rolfe wound up the 1934 campaign playing third base. The Yankees finished in second place, and some of the metropolitan scribes were skeptical of Red's chances of sticking.

Came the season of 1935 and Red was a fixture at third. He played in every one of the 152 games, finished with a season's batting average of .300, though Col. Jake Ruppert's ball team again had to be content with second money.

LED LEAGUE'S THIRD BASEMEN

Last year the Dartmouth boy was the class of the league's third sackers. First in fielding, he had also been hitting. On a dub notable for its heavy artillery, he douted the old apple for an average of .319. He had been a pleasant surprise, even to the astute Massa McCarthy, to the practical-minded Colonel, to his most ardent followers among Dartmouth alumni, and to his friends in the old home town. We had been led to believe that Red didn't have enough arm for the job at the far turn, but Rolfe's whip answered all questions. He had been making amazing plays, he had proved he could go to his left with anybody .... and he had been hitting.

He climaxed one of the most brilliant chapters in all of Dartmouth's post-graduate sports annals by playing an important role in the Yankees' World Series triumph over the New York Giants. His 1936 performance rated him a substantial boost in salary and he returns this spring to the big league wars with all the coolness, poise, and quiet self assurance that sets the veteran so distinctly apart from the rookie.

And realizing that I wondered just how he had achieved the great jump from college ball to the big time, how he felt "inSlde" at having attained such an exalted Position and, for that matter, how he happened to choose such a profession in the first place. I wondered how often now his thoughts turn back to Dartmouth days, just what reminiscences of baseball experience at Hanover had stuck with him, exactly the difference between pro and college baseball as he sees it. Just what does the college player have to go through before he feels confident of doing a good job in the major league?

These and many other questions Rolfe answered one afternoon not long ago. He was cornered in the locker rooms in the basement of the Concord Y. M. C. A. He had just finished taking a shower after a two-hour practice with the Concord Business College basketball squad. In a week he was leaving again for Huggins Field, St. Petersburg and the annual tune-up for another pennant race.

It was the day before his basketballers' objective game. He had coached them successfully through an arduous schedule. His team, which in the past three off-seasons between baseball campaigns he had established as one of New Hampshire's standouts, had won 11 games, lost but four. One of those defeats had come at the hands of the Dartmouth freshman quintet.

Unlike the average big leaguers who fritter away their off seasons, having one grand and glorious loaf, Rolfe wastes not a second after a pennant race closes in rushing back to his native Penacook, and remaining there, improving mind and body until he's called south for another diamond campaign.

Not that Bob doesn't have his fun. He does considerable hunting through the New Hampshire hills. He attends all Dartmouth football games. He toots a mean saxophone, harmonizing with his charming wife, who bats for 1.000 in the piano league. He has a flair for badminton and used to engage the writer in squash racquets until he decided the game was injurious to his throwing arm and shoulder muscles. But Rolfe's principal off season interest is his basketball team.

He leaned back on the bench and his keen, blue eyes twinkled under heavy, reddish lashes. He seemed to be looking at a distant day, long ago and far away. As always he was a bit diffident, somehow a little shy, a little averse to talking about himself.

"It's very peculiar," he said. "You see when I got through high school I went down to Exeter and from there on it seemed as though I just got the breaks. You can't deny it, luck plays a big part. I loved the game and everybody put themselves out to give me a boost.

"One of the first things a college ball player has to do to fit himself for the major leagues is to build himself up physically for the hard grind of playing every day. These minor league camps are no tea and cakes resorts, you know.

"When I first arrived at Albany the trainer gave me some exercises, just routine stuff, to strengthen my legs, arms, wrists. I needed 'em badly. At Hanover we thought we were in pretty good shape. We practiced every day from 2:30 to 4:30, sometimes till after dusk. But the season was short and though we did take spring trips to Princeton and, one year, to Virginia, it wasn't like travelling in the minor leagues.

"After ten days warming the bench witli the Yankees in mid-July, I arrived at Albany and life was just one bus ride after another. We played every day and often at night. It was nothing to hop a rickety bus at New Haven around 11:30 on Saturday night and then travel all night, arrive in Albany at 5 o'clock the next morning, sleep till 11, and then go out to the ball park and play a Sunday afternoon doubleheader. We used to lose those twin bills regularly every Sunday Did all right on the road, but at home we were awful.

HEAVY DUTY ON THROWING ARM

"A major leaguer has to go through that toughening process before he begins to think of 'going up.' Then, too, in major league ball you have to take more care of your throwing arm. You do a lot more of steady throwing than you ever get in college before your whip is ready. You build up your legs naturally by constant playing.

"The greatest difference between college and big league ball, as I've found it, lies in the pitching. Every big league twirler is slightly faster, not nearly as wild, has better control and works on a batter much more than do college hurlers. In college, you see, we played a team only twice in a season. 'Toss 'em up and try to get 'em out!' That was our motto.

col"But in professional ball we have to know all about every man on the other seven clubs. We study their weaknesses, their strong points. Rival pitchers learn our hitting weaknesses, rival fielders our batting peculiarities. There's much more 'inside baseball' to major league play than in the college brand. There wasn't, in lege, nearly as much hit-and-run strategy, but there was a lot more base stealing, the catching being as a general run much weaker.

"Breaking into a major league infield requires intensive study of opposing batters' habits, tendencies, idiosyncrasies, whatever you want to call 'em. Some batters, on the hit-and-run play, invariably hit through second base, others through short. We have to learn which.

"Acquiring confidence, too, is a big factor in the growth from bush league to major league status. It comes gradually. I became more sure of myself the longer I played. Association with and playing against the big-name stars effects a change in one's mental attitude .... and that's very important.

"I was actually scared by the reputation of men like "The Babe," Gehrig, Crosetti, Dickey, and Lazzeri. It seemed as though I'd been reading about them ever since I was a kid, and I'd idolized them, set them apart, then discovered on closer acquaint- ance that they were human after all.

"Enthusiasm means a lot, too. You've got to love the game and be willing to work at it as you would at any other business or profession.

"But the pressure is off now. I had to work hard, desperately, the first and second spring training seasons. I put everything I had into making good. Now I feel like one of the gang, I suppose you'd call it 'veteran's attitude.' Constantly meeting and playing 20 or 30 different situations makes for an almost automatic reaction, whereas in college ball you never get the variety that makes for that poise which is so essential in the crises.

"In the critical stages of a ball game the major leaguer must be able to react instantly. To make the right play at the right time when every second is precious eventually becomes second nature.

"The commercial aspect of big league ball makes it a far cry from the pleasant excitement of 'going out for the team' in college. You go through a lot of ball games to achieve that necessary coolness under fire.

"College men who excel at baseball are crazy not to play pro ball for two years or so at least after graduation."

(Only other Dartmouth athletes of recent vintage to go into baseball were Bill Breckinridge '30, who signed with the Athletics in 1929 and then left after one season to practice law; Foster Edwards '25, who was with the Yankees three or four seasons; Lauri Myllykangas '31, who is still with Montreal in the International; and Ted Olson '36, who is now getting a trial with the Boston Red Sox.

Before we let Red slip away to his wife and belated supper, we asked him if there was any one thrill that stood out above all others in his memories of college days.

"I shall never forget," he said, "one incident which taught me the value of preparing for any emergency. We were play, ing Cornell in the Commencement day game in Hanover in '31. It was the last game of the year. For three years I had never had a chance to use a particular play on which Jeff Tesreau had coached me from the beginning of my sophomore year.

"Memorial field is a wide open one, and if the batter hit a line drive into left field, the shortstop was supposed to go out and take the relay, prepared to throw through to the plate to get any base-runner coming home. I worked on that play, often until dusk, but never in a home game did I have occasion to take a relay on a hit of that kind.

"It was in the first of the ninth inning, the score was tied, o to o, when the Cornell captain laced one over my head into deep left. I went out to get the relay, the throw came in just as the Cornell man rounded third and started for the plate. We got him at the plate and it saved a ball game.

"There was one man out at the time, no one on, and we got the next batter on an infield fly. It was only a routine two-throw play but I had worked on it so much that when the chance finally came, and it saved the game, I got a big kick out of it."

Red didn't mention the time he banged out six hits in as many trips to the plate against Penn at Philadelphia, but that's the way he is, modest, warm-hearted—always a ball player's ball player. A perfect team man. Just ask those ex-collegians Bill Dickey or Earle Coombs, Gehrig, Murphy or Broaca. They will all give you the same answer.

And we're thinking it's not because they are his brothers under the sheepskin, either.

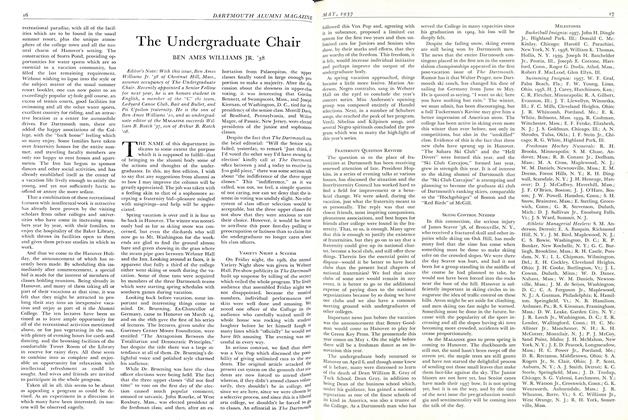

NAMES MAKING BASEBALL HISTORY—ROLFE, LAZZERI, CROSSETTI, GEHRIG

BIG LEAGUE DEBUT Rolfe as he appeared when he first joinedthe Yankees in 1933.

ROLFE HITS A HOMER IN THE DARTMOUTH-PENN GAME, 1930

Sports Editor, Concord (N. H.) Monitor

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1928

May 1937 By LeRoy C. Milliken -

Article

ArticleGradus Ad Parnassum

May 1937 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

May 1937 By BEN AMES WILLIAMS JR. '38 -

Article

ArticleDeath Ends Active Dartmouth Life

May 1937 By NATHANIEL G. BURLEIGH '11 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1914

May 1937 By Edward Leech -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1926

May 1937 By Charles S. Bishop

Article

-

Article

ArticleGraduate Fellowships

April 1931 -

Article

ArticleFund Holding Its Hot Pace

JUNE 1964 -

Article

ArticleThe Ledyard Bridge

February 1940 By AMOS N. BLANDIN JR. '18 -

Article

ArticleClass Notes

Jan/Feb 2001 By Brian Walsh '65 -

Article

ArticleGender and Power in Shakespeare

OCTOBER 1997 By Kathleen Burge '89 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

March 1944 By Robert B. Hodes '46, USNR