Edited with a history of the case by Sidney B. Whipple '10. New York, Doubleday, Doran & Cos., 1937. Pp. 565- $3.50.

This book is the second volume to be published in the Notable American Trial series, of which Edmund Pearson's "Trial of Lizzie Borden" was the first. Anyone who has read and enjoyed Pearson's excellent analysis of the famous Borden case of the early nineties will likewise be fascinated by Sidney B. Whipple's definitive and comprehensive book on the greatest "cause celebre" of the present century.

The actual trial testimony contained in the volume, as edited by the author, presents all the significant details which led to Hauptmann's conviction. The testimony itself offers the reader dramatic and exciting reading.

The 86 page essay by the author which prefaces the book is an excellent work of clarification of the whole complex matter of the crime itself and the ensuing trial. No one who has a genuine interest in really understanding the complicated aspects of the case can afford to miss reading every word of this essay.

For instance, the author makes clear and intelligible the curious aftermath of the case involving such matters as Governor Hoffman's espousal of Hauptmann's cause, the determination of Col. and Mrs. Lindbergh to leave with their son Jon for England amidst the rising tide of public clamor, and, finally, the Means and Wendel "confessions," the latter involving kidnapping and torture.

The author's factual analysis of the case shows that the crime was one of the most daring exhibitions of criminal conceit in American history. We can be sure now that it was undoubtedly conceived and executed by a lone amateur who was able to elude the police for 30 months after the commission of the crime. The theory often advanced that the kidnapping was an "inside job," conceived or abetted by servants in either the Lindbergh or Morrow household, proves to be an untenable one.

It is fascinating to follow the author's description of the brilliant scientific detective work of Arthur Koehler, wood technologist of the Forest Service of the Dept. of Agriculture, who, with no knowledge of where the trail would lead when he set forth on his scientific quest, traced with mathematical sureness the lumber of the kidnap ladder to a Bronx lumber yard. The ladder evidence of this dogged, thorough scientist, together with the spell- ing and hand writing in the ransom notes, sealed the doom of Hauptmann, the Bronx resident, once he was captured.

The author's tribute to Justice Trenchard is a refreshing aspect of this lurid case. The correctness of Justice Trenchard's position throughout the long trial cannot be successfully challenged, according to Mr. Whipple. He says that the defendant's right to a fair and impartial trial was safe-guarded under very difficult conditions largely because the attitude, manner and conduct of the Court itself was beyond reproach or criticism.

Since more than a million words of evidence were heard in the trial, it will be appreciated what a difficult task was undertaken by the author in presenting a review of all the salient testimony. Mr. Whipple is the opinion that a perusal of the testimony shows that the State had a well-knit and carefully conceived plan of attack whereas the defence relied in large part upon rumor, conjecture and innuendo to divert the jury's attention from the main issues. He claims that the defense, in fact, presented not one theory but a dozen, all conflicting.

Mr. Whipple also comes to the defense of the much-maligned "Jafsie." He and Arthur Koehler were the key figures in the case. Why, it is asked, did this 74-year-old man inject himself into the negotiations at such personal disregard for his own safety with the possibility of tragedy at the end? Was he eccentric and abnormal, as many claimed he was? The explanation, according to the author, lies psychologically in the personality and mentality of a man who was patriotic and sentimental to an unusual degree. The author casts aside all insinuations and maintains that his honesty of purpose has been clearly established.

One final consideration remains concerning the question, frequently asked by those who completely disregard the evidence and believe either that Hauptmann was innocent or that he had accomplices, namely,—"Why didn't Hauptmann 'crack' "? How was he able to withstand the terrific cross-examination by Prosecuting Attorney David Wilentz? Why did he profess his innocence to the end? Was this a superman? A megalomaniac? Dual personality? Mr. Whipple's analysis of this phase of the case is intensely interesting and thought-provoking.

In conclusion, one can only urge those interested in knowing exactly how Bruno Richard Hauptmann, author of the greatest crime of the century, was finally defeated by "little men, little pieces of wood, little scraps of paper," to read Sidney Whipple's superb essay and the important trial testimony contained in this volume.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

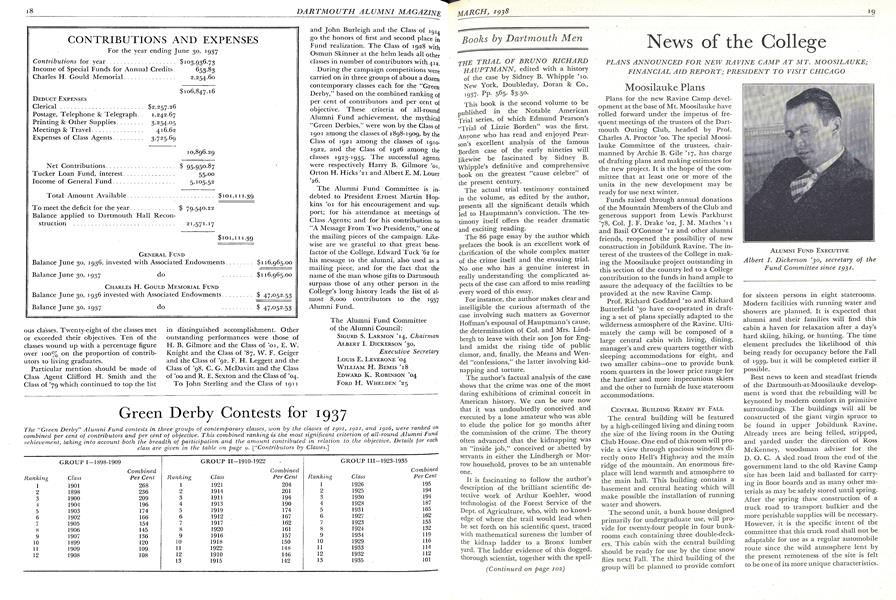

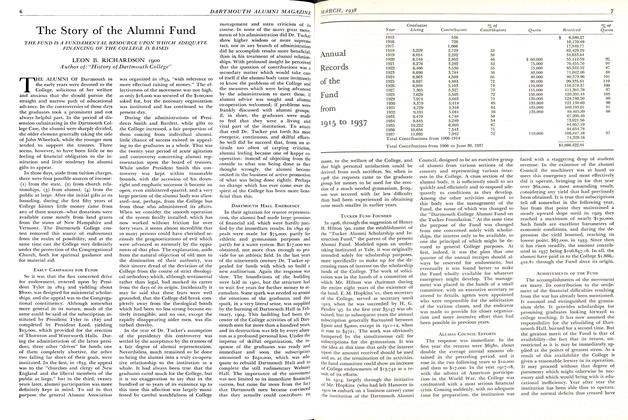

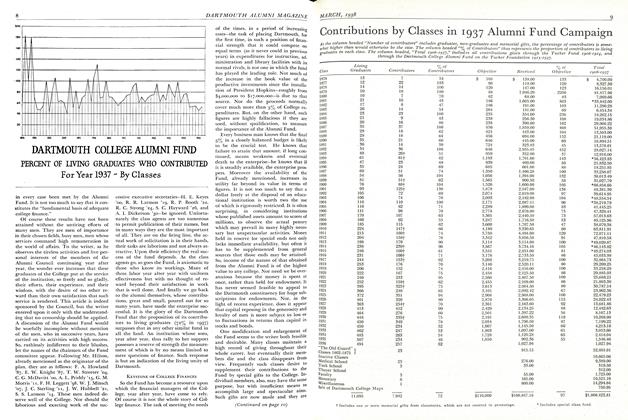

FeatureThe Story of the Alumni Fund

March 1938 By LEON B. RICHARDSON 1900 -

Feature

FeatureReport of 23rd Alumni Fund Campaign

March 1938 By SIGURD S. LARMON '14 -

Feature

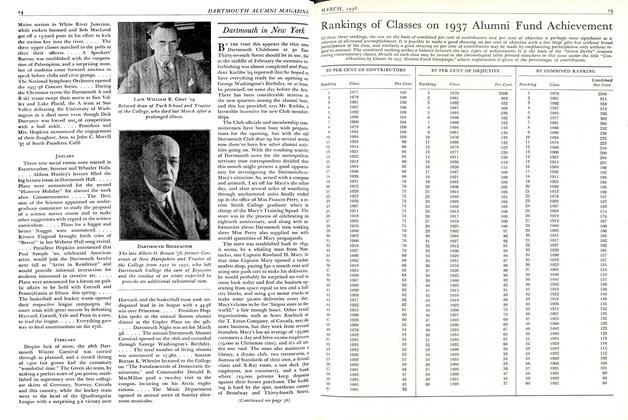

FeatureRankings of Classes on 1937 Alumni Fund Achievement

March 1938 -

Feature

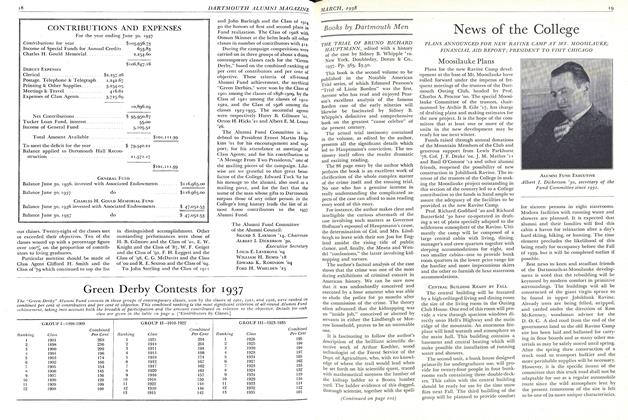

FeatureContributions by Classes in 1937 Alumni Fund Campaign

March 1938 -

Feature

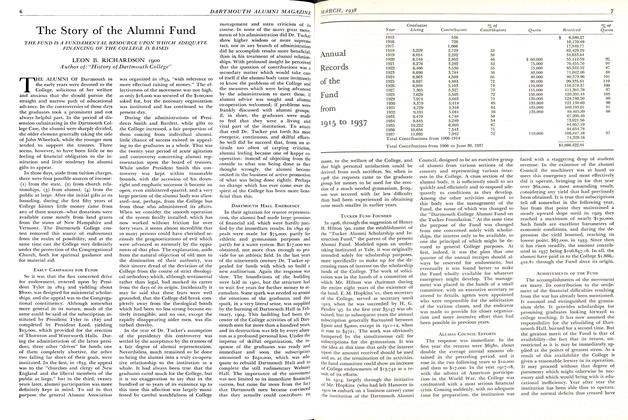

FeatureGreen Derby Contests for 1937

March 1938 -

Feature

FeatureAnnual Records of the Fund from 1916 to 1937

March 1938

Ralph P. Holben

-

Books

BooksSocial Problems and Education

March, 1926 By Ralph P. Holben -

Books

BooksOUTDOOR RECREATION LEGISLATION AND ITS EFFECTIVENESS

JUNE 1930 By Ralph P. Holben -

Books

BooksANTICIPATING YOUR MARRIAGE.

November 1955 By RALPH P. HOLBEN -

Books

BooksTHE STORY OF BLINDNESS.

July 1956 By RALPH P. HOLBEN -

Books

BooksSOCIETY AND CULTURE.

November 1957 By RALPH P. HOLBEN -

Books

BooksSOCIETY AND CULTURE.

February 1962 By RALPH P. HOLBEN

Books

-

Books

BooksPAUL KLEE AND CUBISM

OCTOBER 1984 -

Books

BooksTHE END IS NOT YET

March 1942 By David Lattimore. -

Books

BooksTHE ECONOMY AND ITS MONEY

November 1948 By G. W. Woodworth -

Books

BooksA NAVAL LOG,

October 1945 By Homer Howard, Lieut. Comdr., USNR. -

Books

BooksDetours (Passable but Unsafe)

May, 1926 By R. C. N. -

Books

BooksSCHOOL AND COMMONWEALTH

June 1938 By Ralph A. Burns.