AND MORE SPECIFICALLY A DEFENSE OF THE PLAN OFTHE COLLEGE IN AWARDING HONORARY DEGREES

Professor of Greek and Latin

TO BEGIN WITH, Commencement at Dartmouth is like Christmas in Dickens. There's the blessed peace of release from the educational policies and politics of the academic year; there's the visible joy of families reunited; there's the glorious pageantry, sometimes vociferous, of the Platonic many who throng in tribute to the tangible and intangible of Dartmouth; and—you remember him there's always Tiny Tim who marches bravely last of all in the procession of the Senior Class.

It is an expansive occasion; blush as they must for their own outraged sophistication, even our hard working professional sophisticates think again of that old alumnus who for many, many years now after every Dartmouth game, every Dartmouth concert, every Dartmouth play, every Dartmouth Commencement, in fact after every Dartmouth anything at all has remarked with tears in his eyes, "Didn't the boys do well." Naive? yes, but glowingly, lovably human.

Speaking of humanity, you should have seen old Professor Pompous's face when on Commencement day and in full, majestic, academic panoply of cap, gown, hood, and august consciousness of personal dignity he was confronted on his very way to the Bema by cherubic Danny Olsen aetat. S. 5 who would, of course, rather play in the Dartmouth band at Commencement than go to heaven and so inquired shrilly, "Do you play in the band?" Nothing sophisticated in this type of situation? Well, no, when you think of it, but we said to begin with that Commencement at Dartmouth was like Christmas in Dickens.

Among the many pleasures of Commencement for me has always been the opportunity to witness the ceremony of conferring the honorary degrees. I freely confess that I enjoy the sight of virtue rewarded and of honor paid where honor is due. For the College to acclaim her sons who have deserved well of the world is to my mind altogether fitting, and for her, in the same spirit, to adopt as members of her family those who are not her sons, but of whom she is as proud as if they were, is equally fitting. Even if upon such an occasion now and again some hardened man of the world becomes so softened for the moment as to lose control of his upper lip, I find that I can overlook it. Sentimentality? Of course, but again like Christmas and Dickens.

But it is ordained that among us there

shall be some in whose hearts the desire to be iconoclastic is stronger than the desire to be honest. Such men will deprecate the emotional connotations of Christmas and Commencement, Dickens and Dartmouth, and will thus come to be admired by adolescents and some others for the deftness with which they prick the bubble of our sentimentality. Here we do not choose to march in triumph widi them but rather to limp along with Tiny Tim.

And now, at last, to the specific purpose of all this. The use of the comparison between Christmas and Commencement, Dartmouth and Dickens, lies in the fact that there appears to be an increasing volume of criticism of the institutionalized Commencement in our colleges and, if we may select an item which we can attempt to treat within the present compass, a criticism of the system under which honorary degrees are awarded.

ALLEGATIONS OF CRITICS

Examples of these criticisms of the honorary degree will be familiar to the reader. Most such diatribes which I have encountered are characterized by the fanatical vituperation of established institutions over which our debunking era forever smacks its lips. The allegations of such critics include the charges that honorary degrees are given in return for or in hope of monetary return to the college, that candidates are selected not because they are worthy men, but because they are good press, and that financial acquisitiveness is a surer way to an honorary degree than intellectual achievement.

For the academic mind at least, when exposed to such attacks upon its fundamental decency, there is satisfaction in returning the fire with bullets of facts and figures. Such missiles are not, we admit, a suitable return for the decayed tomatoes hurled by our gleeful critics, for the display is less splashy, but, we fondly trust, the general effect of facts, like bullets, is surprisingly permanent. And another difference: we veteran academics never fire until we see the whites of their eyes. In some such spirit I have compiled the facts about honorary degrees awarded during the administration of President Hopkins. My purpose was entirely selfish, but such comfort as the results may have I here share with those interested.

In this period of 22 years (1916-1937) the College has conferred, according to my count, 258 honorary degrees; the largest

number at any Commencement was 19 (1923) and the smallest number was 9 (1926, 1931, 1932, 1934, 1935); the average is about 12. This average when compared with the usual number at other institutions seems large to a recent critic of the policy at Dartmouth. It is important to note, however, that Dartmouth practice here as in some other matters differs from the usual in an essential particular, viz. the honorary degree of Master of Arts is given to certain members of the official family. The honorary M.A. is awarded by the trustees, in privatim, to- members of the faculty who are elected to full professorships and who either do not hold any degree from Dartmouth, or do not hold a degree of that grade. So far as I am aware, this practice is not followed at other comparable institutions.

NUMBER OF DEGREES AWARDED

For a considerable number of the 22 years in the period under discussion, honorary degrees of Master of Arts in this special category were listed with other degrees in the General Catalogue, a natural source of information about honorary degrees for any interested person. The number of such degrees awarded to members of the faculty should, of course, be deducted from the total before any comparison with other institutions can be made or any average struck. If we do subtract this number, the average per annum is reduced to about 9.

Dartmouth has awarded in this period 10 types of honorary degrees. The honorary degree most frequently given has been Master of Arts (86); next come Doctor of Laws (61), Doctor of Letters (38), Doctor of Science (32), Doctor of Divinity (22), Doctor of Pedagogy (10), Doctor of Music (4), Doctor of Engineering (3), Doctor of Humane Letters (1), and Doctor of Commercial Science (1). Of this total (258), 85 have been awarded to Dartmouth men, 173 to others. All but 11 degrees have been given to Americans and all but one to men (Dorothy Canfield Fisher received the honorary degree of Doctor of Letters in 1922).

The refutation of the claims of those critics who accuse the colleges of sinister motives in their choice of recipients of honorary degrees is implicit, so far as Dartmouth is concerned, in the following tabulation. If the list of recipients is divided according to occupation, we see that by far the largest group is that of the educators (117). Next come in order the 38 professional men (20 clergymen, 10 lawyers, 8 physicians); statesmen, judges, diplomats (30); authors, editors, critics (28); scientists, engineers, inventors (18); business men (16); artists (6); musicians (3); actors (2).

Can any committee of any college faculty, even granted that it is eager to earn money and renown at any price for its

institution, be thought so stupid as to choose over the period of a generation almost 50% of its candidates for the honorary degrees at its disposal from the country's school and college teachers and 6% from the country's business men? It is equally hard to believe that one's colleagues have chosen more clergymen and more inventors than business men, if we assume that money was their object. Furthermore, very few of the business men selected were capitalists of impressive wealth, and in no case, it is amply clear to an impartial mind, was anyone selected for this reason.

A VANISHING RACE

Perhaps here is enough of specific fact, although more might be adduced, to permit a general conclusion. The critics of our system of bestowing honorary degrees have been clever but unwise, scintillating but misinformed, fashionably facile but fundamentally dumb. They have the light touch. Now there are many occasions when that attitude of mind popularly called the light touch is appropriate in thought and speech, but the misuse of this manner of expression, which seems to be perilously prevalent in our day, tempts one to point out that for some themes and in some moods the light touch is less to be desired than the unfashionable firm grasp of the subject, even less to be desired than a plain spoken wallop. In brief, our critics remind me (and not so oddly either) of the woodpecker that spent every morning all last spring from dawn to just before my eight o'clock class drilling at the copper ridgepole which caps the slate roof right over my bed. I gathered that he was probably hunting for larvae, as some critics hunt for scandal, and I felt confident that by trial and error he would discover that larvae are exceedingly uncommon in solid copper. For some days accordingly I regarded the woodpecker's resonant tapping as delightfully whimsical; the joke was on him and a joke on a woodpecker seemed a diverting novelty. Soon, however, I came to feel that the bird was definitely psychopathic, next that I was—or soon should be. From this I fell naturally into contemplation of the probable effect of a shot-gun shell upon the slate roof. At once the bird migrated; sic semper, with woodpeckers and, I hope, with critics of Commencement.

But it is difficult to leave the matter just here. I believe that alumni readers will feel, as the writer does, that a refutation of unfair criticisms of Dartmouth, if it is to have any significance at all for us, must not be concerned solely with facts and figures. Far more important to us are the persons against whom such unfair criticism is leveled, for they are in most cases our friends, or our colleagues, or our neighbors. Recipients of honorary degrees at Dartmouth are selected (from a list of

candidates nominated by the faculty, the trustees, and other groups or individuals) by a joint committee of the trustees and the faculty of the College. Now whatever the situation may be elsewhere, we who live or have lived in the village of Hanover know our friends and neighbors well and normally we feel that an attack upon the sincerity of a committee selected from ourselves to represent ourselves is an attack upon ourselves. If this be insularity, make the most of it.

At all events, such issues as the present matter are perhaps a simpler problem for us than they would be in a more urban environment for we have a rich and varied background of intimate human experience against which we view all such things. Quite naturally then for us the question of the spirit in which Dartmouth awards its honorary degrees, should such a question arise, is merely a matter of examining the reasons assigned in the formal citations when degrees are granted at Commencement in the light of our own knowledge of the characteristic motives of the individuals who grant them. It is certain that anyone of us who reads with this spirit the words in which degrees have been bestowed will be reassured in his belief that these words are worthy of the sincerity, sound judgment, and fine idealism of the men who grant and who receive our degrees and that these words and these men are alike worthy of the College.

The qualities sought may be illustrated by these: "zeal as a discriminating student," "solicitude for the cause of religion in its broader aspects," "sound scholarship and simple courtesy," "a sense of obligation

to society at large," "honesty, courage, and intelligence." The men selected for this honor are typified by these: "skilled practitioner and beloved minister of healing," "keen in understanding and friendly in counsel," "quick in understanding, lucid in explanation," "intelligent and uncompromising adherent to the highest ideals of your profession," "careful student of how best men may live and work together," "exemplar of a devoted spirit of service," "gentleman of culture." Thus is the general rightness of the honorary degree made clear to me.

OUTSTANDING CHARACTERIZATION

Among the many suitable awards which I recall with pleasure, one of the most fitting was the granting of the Doctorate of Letters to Mr. Timothy Cole in 1930. The pleasure of the recipient was so genuinely expressed in his quiet smile, the greatness of his spirit made so clear to us all in some way by his gentle demeanor, and the words of President Hopkins were such a remarkably accurate expression of what the audience clearly wanted to have said in its behalf, that I will quote these words here:

"Extraordinary in talent and preeminent among American wood engravers,recipient of the world's highest awards andprizes for supreme accomplishment withinyour sphere, author of standard monographs upon the lives and works of oldmasters, you have achieved the high position which is yours through indefatigableindustry, the overcoming of hardshipswhich would have daunted one withoutyour stoutness of heart, and the receptivity

of mind to improvize and utilize newmethods when these seemed good. Possessed of skill as is no living engraver, youinterpret onto wood the souls of greatpaintings. Discriminating in your choiceof subjects, and supreme in your technicalskill, you have rightly been characterized

as having the hospitality of mind to respond emotionally to great art and thegenius by your magic to evoke a like emotional response in others. In acclaimingyou the College honors itself as it confersupon you the honorary degree of the Doctorate of Letters."

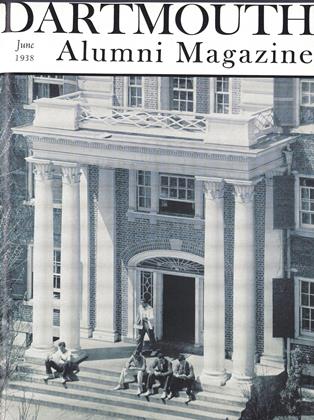

LOOKING TOWARD THE VILLAGE FROM THE FOURTH GREEN AT HILTON FIELD

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1918

June 1938 By Allan C. Gottschaldt -

Class Notes

Class NotesGlass of 1929

June 1938 By F. Williams Andres -

Article

Article"Grand Old Man" Passes On

June 1938 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1930

June 1938 By Albert I. Dickerson -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1937

June 1938 By Donald C. McKinlay -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1934

June 1938 By Martin J. Dwyer, Jr.

JOHN B. STEARNS '16

-

Article

ArticleGEORGE DANA LORD

August 1945 By JOHN B. STEARNS '16 -

Books

BooksALL THE BEST IN THE MEDITERRANEAN

March 1952 By John B. Stearns '16 -

Feature

FeatureA Teaching Boon

MAY 1957 By JOHN B. STEARNS '16 -

Books

BooksTHE POETRY OF GREEK TRAGEDY.

July 1958 By JOHN B. STEARNS '16 -

Books

BooksHESIOD: THE WORKS AND DAYS, THE-OGONY, THE SHIELD OF HERAKLES.

January 1960 By JOHN B. STEARNS '16 -

Books

BooksTHE THREAD OF ARIADNE: THE LABRYINTH OF THE CALENDAR OF MINOS.

DECEMBER 1972 By JOHN B. STEARNS '16