THE THREAD OF ARIADNE: THE LABRYINTH OF THE CALENDAR OF MINOS.

DECEMBER 1972 JOHN B. STEARNS '16By Charles F. Herberger '42.New York: Philosophical Library, Inc.,1972. 158 pp. $l2.

Professor Herberger, like Theseus, has followed the gossamery thread of Ariadne through the Labyrinth of Minoan civilization and, I am convinced, slain the Minotaur, this time for good. Ariadne, he believes, was a Cretan moon-goddess of life in death and death in life, the spouse of the sun-god, also his mother, his sister and his slayer. Their cult resembles that of Ishtar and Tammuz, Isis and Osiris, Venus and Adonis. Careful examination of sculptures, frescoes, inscriptions, gems, seals and the tablets in Linear B script at Herakleion, Knossos, Phaistos, Stonehenge, the Ashmolean Museum at Oxford and elsewhere indicates that the Minoan religion was based upon recurrent festivals symbolic of the mystic marriage of the sun and moon from which the Olympic games were derived.

The Labyrinth thus becomes a symbol of the underworld and the Pillars of Herakles are no longer Gibralter but the gate to the afterlife. The Minotaur with the head of a bull and the body of a man is a transitional stage from the theriomorphic symbolism of the Bronze Age to the anthropomorphism which has dominated Western thought ever since.

Professor Herberger believes that the Minoans emphasized synthetic rather than analytic methods and cautions us against assuming that they were trying their best to think like us but made a mess of it. Myth is one form of synthesis, and it is from this "swan's egg of Leda" that the creative energies of Western Civilization were born. Daidalos the creator of the Labyrinth was both scientist and poet, master of mathematics and music, religion and athletics, dancing and drama because he was at home in the realm of mythopoeic thought. Icarus the eager but naive son of Daidalos flew so near the sun that he melted the scientific wax from his wings and ended in the abyss of analytic logic. Professor Herberger poses a pungent question: "Is mythopoeic thought lost to man, superseded by the mechanistic logic of the computer?" His answer is optimistic: "I think not-or not for long. The substance of thought is forever in flux, but the forms remain the same." This seems to me both true and important.

The primary purpose of this book is closely reasoned scholarship, but it seems, to be written with the humble hope that the general reader will understand and enjoy it. The author is well aware that Crete in the Spring is beautiful with pink almond blossoms, red and white anemones, asphodel and golden oxalis and that in the autumn we can still watch, as Homer did, the setting of the Pleiades and the noisy flight of the migrating cranes. Come to think of it, Homer had a pretty fair grasp of synthetic thought. "Crete," he says, "is fair and fertile. Therein are many men and ninety cities. There too is Knossos, a great city, where Minos was king, a friend of almighty Zeus." Right on, Homer.

Mr. Stearns is Daniel Webster Professor andProfessor of the Latin Language and Literature, Emeritus, Dartmouth College...

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe U.S.-Canadian Relationship

December 1972 By JOHN SLOAN DICKEY '29 -

Feature

FeatureEgyptologist

December 1972 By MARY ROSS -

Feature

FeatureHall of Hallmark

December 1972 -

Feature

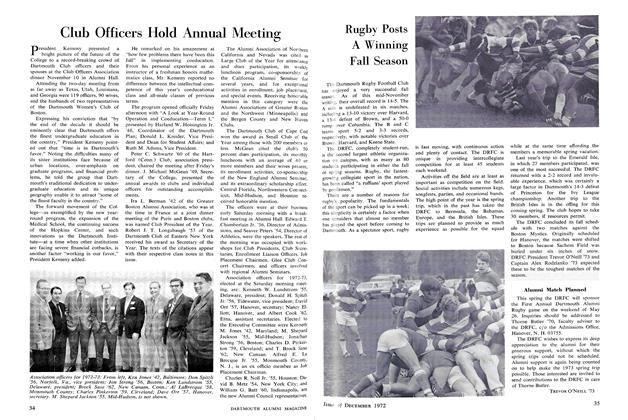

FeatureClub Officers Hold Annual Meeting

December 1972 -

Feature

FeatureRugby Posts A Winning Fall Season

December 1972 By TREVOR O'NEILL '73 -

Article

ArticleFaculty

December 1972 By ROBERT B. GRAHAM '40

JOHN B. STEARNS '16

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters to the Editor

DECEMBER 1971 -

Books

BooksEURIPIDES II.

July 1956 By JOHN B. STEARNS '16 -

Books

BooksOUR FLIGHT TO ADVENTURE.

January 1957 By JOHN B. STEARNS '16 -

Books

BooksTHE POETRY OF GREEK TRAGEDY.

July 1958 By JOHN B. STEARNS '16 -

Books

BooksHESIOD: THE WORKS AND DAYS, THE-OGONY, THE SHIELD OF HERAKLES.

January 1960 By JOHN B. STEARNS '16 -

Article

Article"In Classic Dartmouth's College Halls"

DECEMBER 1966 By John B. Stearns '16

Books

-

Books

BooksFACULTY PUBLICATIONS

March 1920 -

Books

BooksAT DADDY'S OFFICE

November 1946 By Alene P. Widmayer -

Books

BooksTHE BRITISH ATTACK ON UNEMPLOYMENT

March 1935 By H. F. R. Shaw -

Books

BooksSAMUEL BECKETT: POET AND CRITIC.

FEBRUARY 1971 By J. D. O'HARA '53 -

Books

BooksHEARING: A HANDBOOK FOR LAYMEN.

November 1959 By SAMUEL C. DOYLE '47, M.D. -

Books

BooksSeagoing Guerrillas

MAY 1978 By WILLIAM J. HURST