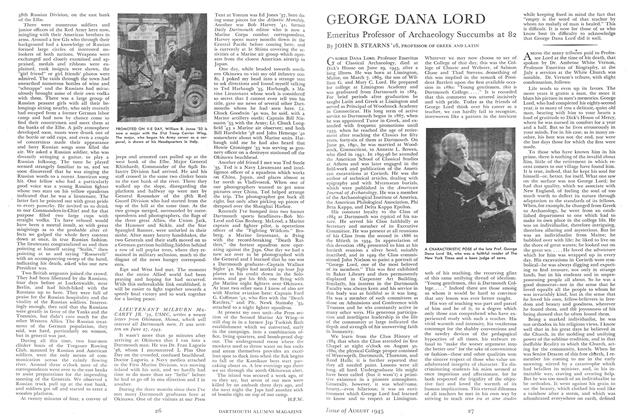

Emeritus Professor of Archaeology Succumbs at 82

GEORGE DANA LORD, Professor Emeritus of Classical Archaeology, died at Dick's House on June 29, 1945, after a long illness. He was born at Limington, Maine, on March 7, 1863, the son of William G. and Mary C. Lord. He prepared for college at Limington Academy and was graduated from Dartmouth in 1884. For brief periods after graduation he taught Latin and Greek at Limington and served as Principal of Woodstock Academy in Connecticut. His long term of active service to Dartmouth began in 1887, when he was appointed Tutor in Greek, and extended with frequent promotions until 1933, when he reached the age of retirement after teaching the Classics for fifty years, forty-six of them at Dartmouth. On June 30, 1891, he was married at Woodstock, Connecticut, to Annette L. Bowen, who died in 1941. In 1895-96 he attended the American School of Classical Studies at Athens and was later engaged in the field-work and publication of the American excavations at Corinth. He was the author of technical articles, dealing with epigraphy and with Mycenaean burials, which were published in the AmericanJournal of Archaeology. He was a member of the Archaeological Institute of America, the American Philological Association, Phi Beta Kappa, and Delta Kappa Epsilon.

His constant loyalty to the Class of 1884 at Dartmouth was typical of his nature. He served his Class faithfully as Secretary and member of its Executive Committee. He was present at all reunions of his Class from the second in 1886 to the fiftieth in 1934. In appreciation of this devotion 1884 presented to him at his fortieth reunion a silver bowl, suitably inscribed, and in 1929 the Class commissioned John Nielson to paint a portrait of "George Lord, one of the most beloved of its members." This was first exhibited in Baker Library and then permanently displayed in Carpenter Art Building. Similarly, his interest in the Dartmouth Faculty was always keen and his service in this body was as faithful as it was long. He was a member of such committees as those on Admissions and Conference with Trustees and he was constantly active in many other ways. His generous participation and intelligent leadership in the life of the community at large indicated the depth and strength of his unswerving faith in humanity.

We learn from the Class History of 1884 'hat when the Class attended its first Chapel at eight o'clock on August 30, 1880, the physical College proper consisted of Wentworth, Dartmouth, Thornton, and Reed Halls; it is further reported that they all needed paint. Lessons were all long, all hard. Undergraduate life might have been called (but it wasn't) a primitive existence in a pioneer atmosphere. Generally, however, it was wholesome, hearty,—even hilarious; it was an environment which George Lord had learned to know and to respect at Limington.

Whatever we may now choose to say of the College of that day, this was the College of Choate and Webster, of Salmon Chase and Thad Stevens. .Something of this was implied in the remark of President Bartlett upon the first available occasion in 1880: "Young gentlemen, this is Dartmouth College " It is recorded that this comment was uttered incisively and with pride. Today as the friends of George Lord think over his career as a teacher, we can hardly fail to recognize, interwoven like a pattern in the intricate web of his teaching, the recurring glint of this same unifying thread of idealism: "Young gentlemen, this is. Dartmouth College. .. . Indeed there are those among us whom it would be hard to convince that any lesson was ever better taught.

His way of teaching was part and parcel of him and he of it, to a degree which only those can comprehend who have experienced study with such a teacher. His vivid warmth and intensity, his vociferous contempt for the shabby conventions and the tawdry devices of the pedagogical hypocrites of all times, his stalwart refusal to "make the worser argument into the better one" for the sake of convenience or fashion—these and other qualities won the sincere respect of those who value unadulterated integrity of character. To discriminating students his mien seemed at once imperious and affectionate, for he both respected the frigidity of the objective fact and loved the warmth of its human implications. This eternal dilemma of all teachers he met in his own way by striving to teach sine ira at sine studio while keeping fixed in mind the fact that "empty is the word of that teacher by whom no malady of man is healed." This is difficult. It is now for those of us who know best its difficulty to acknowledge that George Dana Lord did it well.

AMONG the many tributes paid to Professor Lord at the time of his death, that spoken by Dr. Ambrose White Vernon, Professor Emeritus of Biography, at the July 2 services at the White Church was notable. Dr. Vernon's tribute, with slight condensation, follows:

Life tends to even up its favors. The more years it grants a man, the more it blurs his picture in men's memories. George Lord, who had completed his eighty-second year, is to many of you a delicate, quiet old man, bearing with him to your hearts a load of gratitude to Dick's House of Mercy, where he was nursed in comfort for a year and a half. But so he lives erroneously in your minds. For in his case, as in many another, his best was not the end, nor were the last days those for which the first were made.

To those who have known him in his prime, there is nothing of the invalid about Him, little of the retirement in which recent comers to our village have found him. It is true, indeed, that he kept his soul for himself—or, better, for itself. What one saw on the surface was not George Lord; he had that quality, which we associate with New England, of feeling the soul of too much worth to deflect its nature through adaptation to the standards of its fellows. When, for example, he changed from Greek to Archaeology, he went from an established department to one which had to make its own place in the college life. He was an individualist, therefore intriguing, therefore alluring and mysterious. But he was an individualist from Maine; he bubbled over with life; he liked to live on the shore of great waters; he looked out on the great sea He loved the adventure which for him was wrapped up in every day. His excavations in Corinth were symbolical—he was always digging and expect- ing to find treasure, not only in strange lands, but in his students and in unprepossessing people all about. So he was a good democrat—not in the sense that he loved equally all the people to whom he was invariably kind, but in the sense that he loved his own, fellow-believers in freedom and beauty and goodness, wherever he found them, and the joyousness of his being showed that he often found them.

Being a marked individualist, he was not orthodox in his religious views. I know well that in his great days he believed in the Church, in the molding and unifying power of the sublime tradition, and in that ineffable Reality to which the Church, acting for the community, kneels. When he was Senior Deacon of this free chtirch, I remember his coming to me in the early morning, stirred by a catastrophe which had befallen its minister, and, in his inimitable way, craving and creating help. But he was too much of an individualist to be orthodox. It went against his grain to see the beauty, which clothed his soul like a rainbow after a storm, and which was adumbrated everywhere on earth, defined and confined in authoritative creeds. Even the ritual, with whose splendor some lovely souls cover over the rough places of doctrine, was too orthodox for him; its implications were too definite for his sense of truth. For at the heart of this man's bubbling, overflowing soul was honesty.

To George Lord, honesty was not a personal idiosyncracy, but a demand of Reality, of Holy Reality, upon his soul. In it he found the anchor of life. So do many men like him, today; Albert Schweitzer, for example, is of his spiritual kin. For to be honest, to delight in the beauty and light of the Gospels, beating down upon the soul, and then to kneel, is to know God. To see in honesty the call of the universe to the individual, as did he, to be content in bearing one's witness to indescribable but not unreverenced or unworshipped truth, is to light many a candle, waiting with smouldering wick, in the dark; it is to find in one's conscience a bridge from this world to the higher world, beyond us, before us, and above us.

Now, honesty of this uncompromising sort does tend to isolate one's soul; sometimes it brings upon one periods of deep depression; but it would not be persisted in, did it not carry in its texture unforgettable moments of grandeur. So George Lord heard the Lord say: "Son of Man, stand firm upon thy feet; behold, I speak to thee." And as he listened, and as we saw his eyes shining, he blessed us. So, thank God. many of us will remember him—listening, shining, searching, chal- lenging. Across his later years of weakness, there shines from his soul to ours the light which lighteneth every man that cometh into the world, but which is reflected with peculiar lustre from men as honest and as affectionate and as reverent as George Lord.

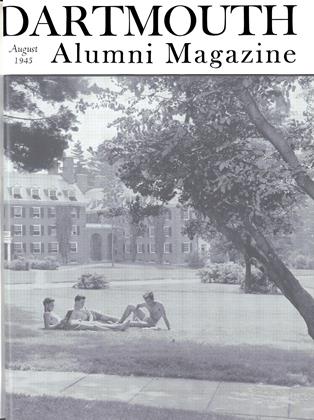

A CHARACTERISTIC POSE of the late Prof. George Dana Lord '84, who was a faithful reader of The New York Times and a keen judge of news.

PROFESSOR OF GREEK AND LATIN

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH MEDICAL SCHOOL

August 1945 By DR. JOHN F. GILE '16 -

Article

ArticleINFANTRYMAN'S BOS WELL

August 1945 By LYNN CALLAWAY '38 -

Article

ArticleLaureled Sons of Dartmouth

August 1945 -

Article

Article'Round the Girdled Earth

August 1945 By H.F.W. -

Article

ArticleMedical School

August 1945 By Rolf C. Syvertsen M'22 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1917

August 1945 By MOTT D. BROWN, DONALD BROOKS

JOHN B. STEARNS '16

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters to the Editor

DECEMBER 1971 -

Article

ArticleA Reply to Commencement Critics

June 1938 By JOHN B. STEARNS '16 -

Books

BooksALL THE BEST IN THE MEDITERRANEAN

March 1952 By John B. Stearns '16 -

Feature

FeatureA Teaching Boon

MAY 1957 By JOHN B. STEARNS '16 -

Books

BooksHESIOD: THE WORKS AND DAYS, THE-OGONY, THE SHIELD OF HERAKLES.

January 1960 By JOHN B. STEARNS '16 -

Books

BooksTHE THREAD OF ARIADNE: THE LABRYINTH OF THE CALENDAR OF MINOS.

DECEMBER 1972 By JOHN B. STEARNS '16