EXAMS IN Hanover: preoccupied student parades to the gym, a myriad of lined-up chairs with arm slabs and blue books, section proctors with fillers and anemic question sheets yellow and pink, a clock hurrying up front, a blue spring sky and a moving labyrinth of new leaves through the windows outside, the fire bell invariably testing at noon, the hard-headed astute and "dull cruds" leaving early. Exams, then Commencement.

It's the end of the year for the three lower classes and it's all over but the sheepskins for the Class of '3B, four years slapdashing by and plunging pell-mell toward Commencement. To look at a senior, with his green blazer and cane, slacks and sport shoes, and compare him with almost any other senior with a green blazer, cane, slacks, and sport shoes, you might be tempted to remark what we heard a man assert superficially the other day, "They all look alike. As a matter of fact they are alike, aren't they? They do the same things, talk the same way, seek the same entertainment I think your average student today is losing individuality and personality."

We thought over what we knew about the boys here at Dartmouth and their activity, and then almost laughed—what the man said was so incorrect. They may appear somewhat the same outwardly, but that's as far as it goes. From the minute of matriculation in freshman year, a Dartmouth man starts out on his own course and may have nothing in common with the next man from then until Commencement. For classification we can start with two broad divisions: Doers and Drones. The drone, for the purpose of description, is the male of the species at this particular Hanover hive, which has no sting and gathers no honey. Because drones at Dartmouth represent a minority we can dismiss them briefly as an unprosperous student-type whose idea of College is a place where you spend four years before getting to Business. If the four years between 18 and 22 are as important a habitforming cycle as people say they are, this group is off to a bad start. The drone attends classes—physically—doesn't know what a Hanover week-end is like, is a "nice guy" with no personality. He gets-2.0 or as much less as he can and still stay in college. If the requirement is 220 points, the drone will graduate with 221. He lights up his cigarette two minutes before the end of each class, punches a new hat until properly slouched, combs his hair carefully, wears his pants high, forms the mass of what are known as "steadies" at the Nugget, gets a beer or milkshake every night at 10, then goes back to the room to bull. The drone's career at Dartmouth, as a matter of fact, is one big milkshake. There are plenty of drones at Dartmouth,, yet they are a decisive minority. But the gentleman's criticism that the modern student has lost individuality and personality rightfully lands on this group.

The drones don't blackmark the doermajority. In a few days most of the 531 students constituting the Class of 1938 will get their diplomas. To state that even one-third of this number have fallen into the drone class would be, we think, an inaccuracy. For if the standards by which a student may lift himself into the worker class are taken into any account, two-thirds of the senior group have long since pushed themselves out of the zone of the drone and semi-drone. The standards of elevation are numerous. The first standard is academic. The senior class has its group of men who have revered high scholastic standing and the ultimate Phi Beta Kappa goal as the best element of their education. So they've plugged for four years and have made good academically. The fact that employers take high scholastic record as the soundest basis of estimation in giving a graduate a job, is in this group's favor. Though these men are often narrow in their perspective of extra-academic matters, they have absorbed the fundamentals of application, can tackle a piece of work, and know how to get things done. These are pretty good traits to have, and one way to get them is through intensive academic application. In the academic class also are the less-brilliant type who get lower grades, but work for what they do get, and are pretty apt to make a showing when they get out. That their record may show an only average standing, means nothing as far as what they have accomplished for themselves at Dartmouth is concerned. A glance at this group's scholastic schedule is often revealing, for these men may have tackled physics and chemistry majors, and have consequently spent almost every afternoon in the lab for the last two years.

The next anti-drone standard is in the extra-curricular activity sphere. This is a big division because you include in it all those men who in four years have vigorously emphasized sports, publications, dramatics, musical organizations—and kept their marks up at the same time. Highest promise goes to the men in this group who have managed to help their outside organization along and get high grades at the same time. They have the benefits of the broadening effect, practical experience, contacts, associations, and the various intangible benefits extra-curricular activities can offer, and at the same time reap the advantages of a high scholastic standing.

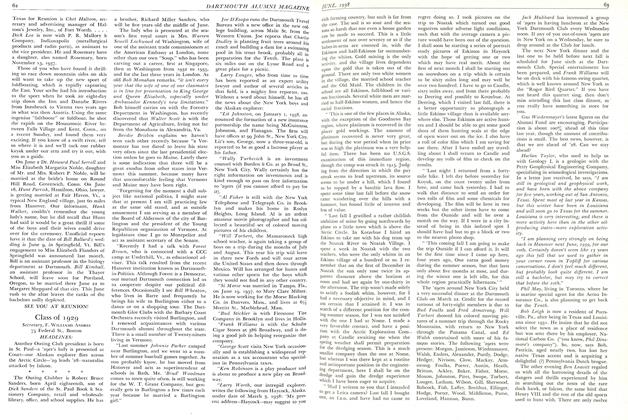

A CAMPUS SUPERSTITION With the exam season approaching, many a Dartmouth undergraduate will follow thissenior's example and rub Dean Laycock's nose for good luck.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1918

June 1938 By Allan C. Gottschaldt -

Class Notes

Class NotesGlass of 1929

June 1938 By F. Williams Andres -

Article

Article"Grand Old Man" Passes On

June 1938 -

Article

ArticleA Reply to Commencement Critics

June 1938 By JOHN B. STEARNS '16 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1930

June 1938 By Albert I. Dickerson -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1937

June 1938 By Donald C. McKinlay

Ralph N. Hill '39

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters

December 1940 -

Article

ArticleSTUDENTS AID HOSPITAL FAIR

May 1938 By Ralph N. Hill '39 -

Article

ArticleLARGE NUMBER WORKING WAY

June 1938 By Ralph N. Hill '39 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

November 1938 By Ralph N. Hill '39 -

Article

ArticleFACTS OUTLINED

November 1938 By Ralph N. Hill '39 -

Article

ArticleADVISORY GROUP SUGGESTED

November 1938 By Ralph N. Hill '39