President Hopkins Renews Faith in Enduring Qualities of Liberal College in Remarks at Opening Exercises

DARTMOUTH'S 171st academic year opened on Thursday morning, September 21, with the holding of the traditional convocation exercises in Webster Hall. President Hopkins presided over the exercises, which were allowed to lapse last year because of the hurricane, and followed his recent custom of speaking informally to the student body and faculty.

The student audience filling every inch of Webster Hall was one of the largest crowds ever to attend the opening exercises. Undergraduate registration on the first day of the new college year was somewhat less than the figure for last year, but late registration is expected to produce a comparable total. The 2,338 men registered on September 21 included 510 seniors, 561 juniors, 617 sophomores, and 650 freshmen.

President Hopkins prefaced his talk with the explanation that he was more inclined to make "remarks" than to make an "address." Following is a slightly condensed stenographic transcript of his talk:

THE AGE-LONG QUESTION which Pilate asked, "what is truth?", is a question which education constantly tries to answer, and the attempt is a variable approaching a limit because it never can be finally answered. The best that can be done is, as each generation comes along, to make the answer a little more definite, a little more assured, and the determination a little more strong that those things which have been proved to be true shall be adhered to. There is a loss of meaning in hackneyed words and phrases. Those things which we have heard most familiarly from earliest times tend frequently to have less meaning for us than those things upon which we have reflected in later life and to which we have come in a spirit of inquiry and from which we have emerged with something in the way of conclusion. And so it is of the word "liberal" which we apply to the college and . the word "truth" by which we define the objective of the liberal college.

Now as I greet the College at this opening I revert to words and phrases that probably have been used in regard to the College from the beginning of time. A few of us—undergraduates, officers of the College, alumni, and others—dwell constantly upon the implications of the College or inquire continuously of ourselves what freedom means, what liberalism means, what truth means. Now the very derivation of the word "liberal" which we use in the term "liberal college" means freedom. The liberal college is the free college. This I have said to the College many times; probably shall say many times more. We cannot too much dwell upon its significance. The liberal college is the free college. But free for what? Free for the search for truth. Well, someone may say, "Hasn't that been true for centuries in colleges?" Yes, some colleges somewhere, but in recent years a decreasing number until at the present time in this great country which we call our own and in those colleges among which Dartmouth is numbered is pretty nearly the last refuge and sanctuary of a spirit which allows untrammeled search for the truth. We are the beneficiaries of special privilege. Take the map of the world; check over the areas, check off the peoples, and see how frequently you will find a place or a people in which you could imagine a college in which there would be the freedom that you have here today conceded to you by membership in this college.

It is worthy of our attention at this time that we live in a country and under a government where this is possible and where this is permissible. It therefore becomes the responsibility of each and every one of us that this search for truth shall be undertaken honestly and with seriousness, that we shall not give snap judgments very much time, that we shall not claim for our unsubstantiated opinions virtues to which they are not entitled, and most of all that we shall not in the acquisition of a little knowledge believe that we have acquired all knowledge and claim special consideration for our opinions based upon half truths or even whole truths plus some margin of error.

ASPECTS OF PROPAGANDA

Admittedly it is a difficult thing to know what truth is at the present day. I was told a few weeks ago on what seemed to me reliable authority that we were to hear in our broadcasts frequent warnings against propaganda and that I might be interested in knowing that these broadcasts were heavily subsidized by agencies which felt that their purposes would be most quickly conserved if there became universal doubt in regard to all propaganda. Propaganda is not necessarily false. In the beginning, the use of the word propaganda, as a matter of fact, was not in regard to fallacies at all or in regard to lies. Therefore, we have to take all that we hear, all that we read, all that we learn in any way at the present time under consideration, and the one great purpose of the College is to inculcate into our minds both the desire to know the truth and some knowledge of how to judge what is truth

It isn't going to be any more easy for undergraduates than it is easy for the population of the country at large to decide what is truth and what is not truth. I think that some of us who had some intimacy of contact with the last war have shrunk a good deal during the past twenty years from interpretations which we have heard given in undergraduate bodies in regard to that war. Part truths, yes; sometimes whole truth supplemented by something which seemed to us very far from truth. But it is the disposition of undergraduates always—as indeed it is the disposition of their elders—to seek simple solutions. Now war springs from the spirit and hearts of men. I have heard made in this hall before the student body a plausible and a persuasive argument, which I think seemed convincing to most of the student body, that munitions makers always made war.

As a matter of fact, within a fortnight after that argument was made here I was having dinner in New York with Charles M. Schwab during which I referred to the talk. He said, "It is a peculiar thing, but I suppose we will never be able to persuade the public that even the munitions makers prefer the steadiness and the stability of peace to the temporary inflation of war." At any rate, whether that be so or not, munitions makers have had very little to do with making this last war; they had very little to do with making the World War; and they had very little to do with making the Civil War. Wars spring from the acquisitiveness for power of certain groups and the resistance to this acquisitiveness by other groups, sometimes largely influenced by self-interest and sometimes more largely influenced by idealism than we are willing to concede at times.

Those of us who were connected with Dartmouth College at the opening of the last war, at least after the American entrance into it, I think have felt at times that we ought to arise in defense of the spirit of the men who went to that war. As a matter of fact, the conditions were very similar to the present. A Prussian oligarchy had got to the point where it desired to dominate the world, and it was felt on the part of many that such domination would be destructive of all for which they and men of their race had worked and lived. Some self-interest entered in undoubtedly, but that was not the dominating motive, that was not the determining factor. I have heard explanations by the Dartmouth undergraduate body of why undergraduates went to war. I have heard about bands playing and banners flying and all that sort of thing, and then I have thought of the days when we of the college staff would come into the offices in the morning and would find the slips that men had left the night before as they had taken the midnight train with the statement that they felt that the time had come when they must go. I am not arguing whether they analyzed the situation rightly; I am not arguing whether or not there was a responsibility upon them to go. I am simply saying that the rationalization done by the undergraduate body in regard to the last war had little semblance of truth, and am thinking that probably there will be little semblance of truth in the analysis of the present day by undergraduate bodies twenty-five years from now. Such are the difficulties of knowing what truth is.

I have heard a great deal about the iniquities of the Treaty of Versailles, with most of which I agree, but in order to understand the Treaty of Versailles, one needs to know the terms of the treaty which would have been imposed upon the Allies if they had lost the war. I have heard no discussion of that, but in order to know truth, it is necessary to know why things have happened; the undergraduate body needs to go beneath the surface of things, needs to understand more clearly than they have understood in the past, and needs to arrive at its convictions on the basis of fuller data. And the only reason for referring to those things at the present time is that we are living in one of the most interesting even if one of the most tragic times in the world's history. Along with all the regret and with all the sense of frustration which comes at the time we nevertheless have ring-side seats at one of the greatest phenomena the world has ever seen, and we would lose the benefit of our education as we would lose great values that attach to the privilege of living in a time like this if we gave ourselves over wholly to despondency and over wholly to pessimism and cynicism, making no attempt to realize wherein lie the origins of things which are happening now, wherein lies the solution—if it may be found—of things that are happening at the present time, and most of all what desirable part we can play in it

The time has come for us to recognize the fact that for seven hundred years the Anglo-Saxon race—l use that blanket term —has been striving to achieve a form of government, an organization of society, and a manner of living which on the one hand should give order to life and on the other hand should give freedom and liberty in the maximum degree to the individual. And the time has come for us to recognize that in our country and among the people whom we know those ideals have been more fully achieved than they have been anywhere else in the world. It has been the vogue for the past two or three decades to emphasize the weaknesses of mankind. If there were any idols among mankind, we have looked for the clay at their feet rather than for the gold above; if we have discussed public men, we have discussed their weaknesses rather than their strength; if among peoples there have been mixed motives of idealism and materialism, we have dwelt wholly on the materialism. For some obscure reason, in our collegiate bodies and among our intellectuals it has become presumably a sign of intelligence to be pessimistic and to be cynical all of which seems to me to be contrary to the spirit of which the college should be representative and contrary to the spirit that will make this eventually a better and a sweeter world. We have talked about realism, but our interpretation of realism has been all in regard to the things that have been unpleasant. There are beautiful things in the world that are very real: a fall day like this in Hanover; great paintings; great music; the fruits of beautiful thinking as exemplified in philosophy. Those things are just as real as the unpleasant things upon which we have been dwelling. They are more real than the basis of any cynicism which we have allowed ourselves to cultivate.

Somebody has said that the youth of the world have become subjective rather than objective. Well, that is not true of all the youth in the world. Unfortunately this matter of subjectivity and objectivity is not very evenly divided. The youth of Germany and the youth of Italy and the youth of Russia are not very subjective, and if we are to hold our own in this world and if we are to make the principles for which America stands representative of the principles which will lead to a better world, we must make ourselves more objective than we have in the past, retaining sufficient subjectivity to make our analysis and our criticism valid but not assuming that criticism is a virtue excepting as it is founded on fact. We have heard a good deal in regard to the folly of some of our Anglo-Saxon ideals. I referred two or three years ago to standing with a friend of mine at New College and his deriding of the motto "Manners Maketh Man." Well, perhaps as a principle of education that ought to be incidental to other things, but nevertheless it has its merit, and if various peoples of the earth had been educated in a system in which it had been emphasized that manners maketh man, fewer nations on the earth would be governed by gangsters and liars and murderers. We have heard and probably most of us have shared sometimes in the derision placed upon the remark of Wellington that Waterloo was won on the playing fields of Eton, but there are manners of sportsmanship which, if inculcated into the minds of men in general, would make impossible not only many of the actions but many of the utterances of the present time

The freedom to think presupposes the disposition to think and the disposition to think presupposes the willingness to think things through. The necessity is upon us as never before for deep and responsible thought, and the student body of Dartmouth College cannot afford at this particular time to indulge itself simply in the pyrotechnics of clever thought. Thought needs to be honest and it needs to be based upon the willingness to think hard and to learn gradually. But in spite of the interest which attaches to contemporary events, I would in the large urge that the student body insist upon not living wholly in the present. An Oriental ruler, according to legend, sent for the wisest men in his realm and he said that he wanted a philosophical aphorism upon the truth of which he could lean, whether in times of exaltation of the spirit or in times of great depression, and the wise men retired and eventually returned with the phrase, "This too will pass."

There is general agreement in the world that the nature of life is pretty largely determined within the years represented by you men who are undergraduates of the College, by the mental pictures which you form of life. In the all-absorbing interest of present-day times let us not forget that even the time from the beginning of the World War until the present is very short. A few years ago in Egypt, our dragoman showed us temple after temple despoiled and wrecked, and in response to my inquiry each time he would say that it was done by the Persians. By and by I said "The Persians must have been here a very long time to do so much destruction as they have done." He said, "Oh no, the Persians were here only three or four hundred years." I began to think of that in terms of the life of the United States.

"This too will pass." How rapidly it will pass or what will be the results of its passing will depend very largely upon the thinking and the consequent action of men such as you are. Therefore I say, live not wholly in the present, because the world has attractiveness, it has values, it has beauties which even if largely hid at the present time, yet are actually existent. It would be a pity for a generation wholly to lose the knowledge of those values or appreciation of them. Looking back over the last quarter century, I think as a matter of fact we too largely have ignored those values in the lives which we have lived since 1914. I would that we might avoid that mistake in our own lives and in the lives of men who come immediately after us

I revert to the aphorism of the advisers of the Oriental ruler, "This too will pass." The world will go on, the world will in the course of time realize again some of the sweetness and light of which it is deprived at the present time. Let us not forget those things.

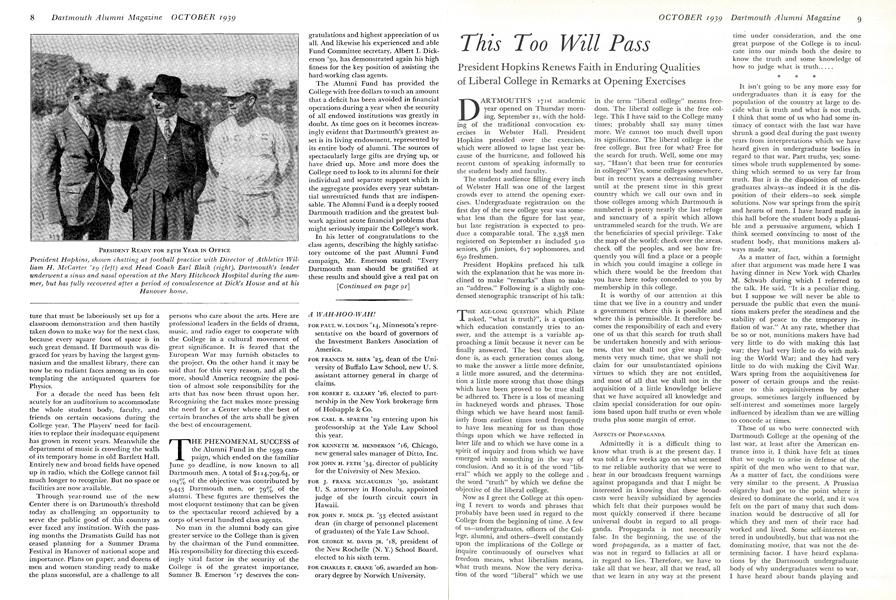

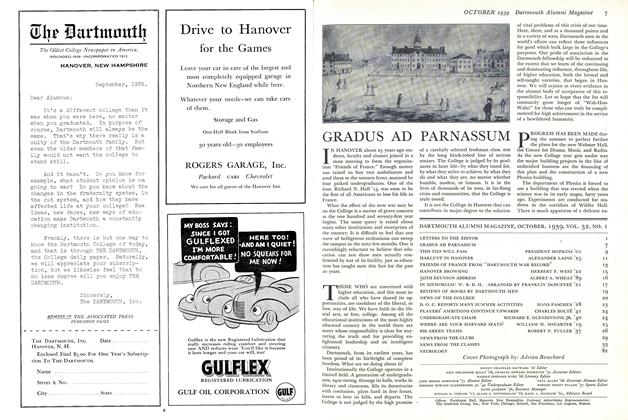

PART OF THE FACULTY (LEFT) ON THE PLATFORM OF WEBSTER HALL SEPTEMBER 21 WHEN PRESIDENT HOPKINS' ADDRESS OPENED THEYEAR; AND (RIGHT) DEAN ROBERT C. STRONG '24 ANSWERS FRESHMAN QUESTIONS AFTER THE OPENING EXERCISES.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleGRADUS AD PARNASSUM

October 1939 By The Editor -

Article

ArticleFriends of France

October 1939 -

Article

ArticleHakluyt in Hanover

October 1939 By ALEXANDER LAING '25 -

Article

ArticleIn Memoriam: W. B. D. H.

October 1939 By FRANKLIN McDUFFEE '21, Anton A. Raven -

Class Notes

Class Notes1912*

October 1939 By CONRAD E. SNOW -

Class Notes

Class Notes1929*

October 1939 By F. WILLIAM ANDRES