WALTER BROOKS DRAYTON HENDERSON, Professor of English, died suddenly at the home of his brother in Montreal on July 10, 1939.

Professor Henderson was born in Brown's Town, Jamaica, in 1887. His grandparents had come there from England as missionaries, and his father had devoted his entire life to this work, so Brooks came naturally by the devotion to teaching and the service of others which distinguished his life.

When he was fourteen he came to the United States and entered Kimball Union Academy; in due course he matriculated at Brown University, taking his Ph.B. degree in 1910. He received his doctor's degree at Princeton five years later.

After serving for a time as an editor for the Macmillan Company of New York, he enlisted as a private in the British Army in 1917, and was gazetted second lieutenant in the Royal Artillery just before the Armistice. During the succeeding years he served as secretary and literary assistant to Winston Churchill of Cornish, N. H., and briefly as secretary to Rabindranath Tagore, during Tagore's American visit. He also served for several years as instructor in English at Yale. He came to Dartmouth as an assistant professor in 1925, and was made a full professor three years later.

His chief works are Swinburne andLandor, 1918—an outgrowth of his graduate work at Princeton—and an epic poem, The New Argonautica, published in 1938. He was also the author of several essays on Shakespeare and on Renaissance patterns of English thought in Shakespeare's works.

So much for the bare facts of his life, which suggest little about one of the most striking and baffling personalities I have ever known. For Brooks Henderson was a creator, the architect and dictator of a world and cosmology of his own. It was difficult for me, at least, to understand or to believe in all the details of its geography, which were as strange as any in Dante or in Milton. The shifting lights and shadows of its countryside never became comfortably familiar to me. From that world all the easy vulgarities which help most of us in ordinary living were excluded: it was the world of a great and imperious idealist, its senate peopled by those images of Shakespeare, Homer, Virgil, Dante, and Milton which Brooks had made in his own image, though surely he had endowed them with nobility, beauty, and light.

Familiar Scenes as ijist Tear Opened

It is hard to write about one at once so gentle, so inflexible!, and so inevitably and tragically aloof, because few of us can know him well, and almost none of us can understand him. I do not think Brooks had any really intimate friends except Shakespeare and the epic poets, to whom he gave his mature life. From them he certainly drew something of his power and his idealism: to them I think he attributed some qualities which were his, not theirs. Certain it is that his life was controlled by one central purpose: to understand and interpret Shakespeare in terms which would make Shakespeare live for youths of today. To this task he brought not only ascetic devotion, but the gifts of imagination and eloquence—an eloquence unrivalled in my experience. Those who have heard him lecture are not likely to forget the intensity, the enthusiasm, the effortless beauty of his speech.

I admired Brooks Henderson for his many gifts, but I also loved him for the underlying sweetness of his nature. It is true that his temper was quick and that he was at times intellectually intolerant, but he was essentially a man thoughtful of others, gentle, generous, exquisitely courteous—not unlike that "perfect Prince of the North" of whom he spoke so often and so well.

TRIBUTES FROM FORMER STUDENTS

It seems to me that the best way of suggesting the impact of Brooks' personality and his power as a teacher will be to print a series of brief tributes from a few of his former students, and from faculty friends. The first of these is from FRANCIS HORN '30.

"It is with deep regret and a genuine sense of personal loss that I have learned of the tragic death of Professor Brooks Henderson. Mine was the rare privilege of having him as tutor the first year the tutorial system was adopted at the College, and it was largely due to his inspiration and his example that I have become a teacher of English. Since graduation I have always kept in touch with him and when I saw him last, a little over a year ago, it was a pleasure to find that he had lost none of the youthful enthusiasm and great personal charm which had endeared him to all who knew him.

"As a teacher he had that all too rare ability of communicating to his students some of his own enthusiasm for and love of literature. If his enthusiasm sometimes got the better of his scholarship, it is easily forgivable in an academic world that has perhaps too little scholarship that is both inspired and inspiring.

"Professor Henderson was a great teacher and a true gentleman. His death is a great loss to Dartmouth, but by many of her sons, I am sure that he will always be remembered with gratitude and affection."

Here are a few further tributes from former students.

"Professor Henderson possessed that rarequality of seeming to discover Shakespearewith his class rather than teaching Shakespeare to the class. As a man, his unwavering belief in truth and beauty was a courageous challenge to the cynicism of theage and a refreshing stimulant to thedoubting student."

RICHARD BABCOCK '40.

"I can honestly say that Brooks Henderson was one of the most inspiring influences of my life.

"I had the good fortune of studying Shakespeare, Milton, Dante, Virgil and Homer with Professor Henderson and he kept me so interested in these men that I put more work into his courses than any others I studied at Dartmouth. I often, playfully, thought of Professor Henderson as a medieval prince himself when he strutted around the campus with his large brimmed hat and cane; yet he stimulated me into a new type of thinking and imbued me with a new esthetic type of beauty. Not always did I agree with his interpretation, but I began thinking in terms of his sensitivity, feeling with him the beauty and violence in the world of yesterday and today.

"Often he would return my essays with B's or C's on them with a little note on the front page saying that I could rewrite the essay as many times as I wished until I finally received an A. In other words, he was more interested in seeing that I learned than merely grading me academically. Many times when I visited his office he gave freely of his time, trying to help me master a subject or discussing with me a current happening, showing how it would have fitted into Shakespeare's or Virgil's scheme of things.

"I believe that Professor Henderson was as great a poet as the poets he taught; not because of the poetry he wrote, but because of his poetic thought. Thus today at work, with my own stodgy problems confronting me, I know I will be more sensitive to my environment and fellow men because of Professor Henderson."

MORTON D. MAY '37.

"My acquaintance with Professor Hen-derson was limited to one semester as oneof his students, but I have always remem-bered him for two striking qualities. Thefirst was his patient ability to show us thecolor and beauty in the literature and peo-ple we studied. He put his soul into mak-ing live the beauties of the past.

"Secondly, I shall always rememberBrooks Henderson for his courage. He wasfrail physically, yet he never hesitated tooppose a stupid act or soundly criticize athoughtless judgment. Dartmouth Collegewill find it impossible to replace him."

WAYNE K. BALLANTYNE '37.

"It is with sadness and great sense of loss that I write on the occasion of the death of Brooks Henderson, my teacher and friend. And somehow the sense of loss is not only personal. One regrets not only the passing of the man, but the obliteration of the drive and sense of direction which was the focus of his spirit. Some personalities are amorphous and leave recollections which are vague and dim. But one remembers Brooks Henderson with crystal clarity not only for what he was, but for what he stood for.

LOVED BEAUTY AND HUMANITY

"He stood for poetry and the love of beauty in a world with precious little regard for either. This, I think, is why he was essentially a lonely man. His world was not the world of commerce or affairs. It was an inner world where poetry was all-important, and where the quest for beauty and the communication of this quest was the final imperative. His response to this imperative was unfailing. Skiing with him upon a moonlight night or listening to him talk of Dante or Milton in the classroom, one was aware of the quality of his understanding, and something of his own high seriousness was communicated to us who listened.

"The world which he inhabited possessed a certain timelessness. For poetry is concerned not only with the things which uniquely occur, but the things in human life which recur. This is the secret of his companionship with Homer and Milton, with Virgil and with Shakespeare. These were for him the real men—the living men. And yet this judgment did not represent a mere aestheticism. His love of poetry was tempered by a philosophic spirit. There was something basically ethical at the root of his unworldliness and in his search for values. He hated brutality and disloyalty so much so that he felt almost as a personal sorrow the horror of the World War and America's betrayal of the League of Nations. His turning to the great poets of the past was in the nature of a flight from chaos.

In his New Argonautica he wrote: Tell me your stars. They make no vainreportHowever in strange tongues their speechis heard.If you have followed them, you have noterred.'

His stars were beauty and humanity. He followed them. He has not erred.

ALBERT WILLIAM LEVI '32.

Department of Philosophy.

The final tribute is from Professor Raven of the department of English, who has been a colleague and friends of Brooks, for many years.

"Brooks Henderson had a fine enthusiasm for literature. It meant to him something more than pastime or delight; it wasthe source and the expression of spirituallife. He devoted himself to it wholeheartedly. More than once he said to methat he was not naturally studious or scholarly, that he had to drive himself to work;but I always doubted this, for he was aneager worker. The meanings in great literature were for him apparently inexhaustible; he conceived of his major prophets,Homer, Dante, Shakespeare, and Milton,as men like himself, men 'voyagingthrough strange seas of Thought, alone'—and Brooks, an intellectual aristocrat, voyaged with them.

"There can be no hesitation in praisingBrooks' enthusiasm in the classroom. Hegave lavishly of his conception of Shakespeare and the others. He acquainted hisstudents, by example, with a new view oflife, with a new world, carrying them withhim and into himself toward a vision. Bymeans of his eloquence—and he couldspeak more beautifully than anyone Iknow—he not only presented, he transmitted to his hearers the enthusiasm thatpossessed him. He was and is unforgettable."

WE'RE OFF TO SEE THE MOUNTAINSNearly 70 years ago C. P. Chase '69 (long-time treasurer of the College) and Nathan W.Littlefield '69 set out from Hanover with the above team to tour the White Mountainsand Northern New Hampshire. They spent the summer of 1870 pioneering in the touristbusiness and visited Connecticut Lakes and the Diamond Lakes in Coos County. Photograph is furnished through the kindness of Mr. Littlefield's son, Alden L. Littlefield '14,and the treasurer of the College, Halsey C. Edgerton '06.

BROOKS HENDERSON His sudden death July 10 was a severe lossto the Humanities of the College, whoseinterests he had championed throughouthis teaching career.

JOINING THE OUTING CLUB (TOP) CARRIES PRIVILEGES THROUGHOUT THE YEAR. (MIDDLE) SOMETHING OLD AND SOMETHING NEW IN PILLOWS. BUSINESS (ABOVE) FOR THE OLDEST COLLEGE DAILY IS GOOD.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

FRANKLIN McDUFFEE '21

Article

-

Article

ArticleAN OPPORTUNITY FOR SERVICE

June 1921 -

Article

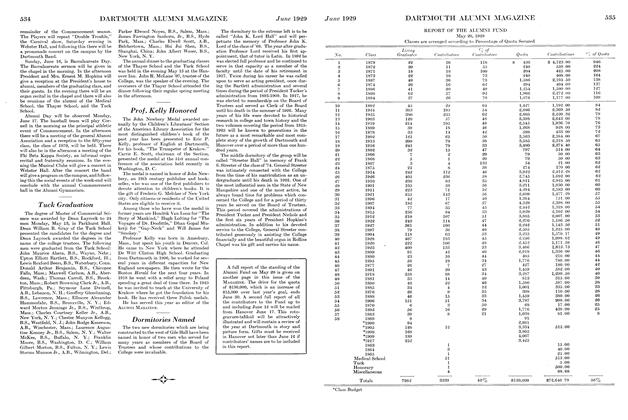

ArticleREPORT OF THE ALUMNI FUND

June 1929 -

Article

ArticleTHE COLLEGE

February 1961 -

Article

ArticleThinking About 9/11

Jan/Feb 2002 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleHonor by Degrees

MAY 1997 By Noel Perrin -

Article

ArticleA New and Effective Religious Organization

April 1934 By Seymour B. Dunn '34