Poll of Students and Faculty Discloses Campus Sentiment on European War

EXACTLY 1500 Dartmouth undergraduates and 100 faculty members went to the polls on October 3d and 4th to express their opinions on aspects of the European war and America's stand on neutrality. This 63% of the student body and 36% of the teaching staff endorsed by an overwhelming vote the Administration's cash and carry program; they favored standing by and studying the European war with an eye toward gaining an intelligent and objectiye viewpoint; but most encouraging of all, Dartmouth students and Dartmouth instructors stood side by side in agreeing that America's entrance into the conflict was far from inevitable.

Actually, it was the faculty who were more convinced that the United States would not be dragged into the war, for their vote registered was 81% against ultimate participation, whereas the undergraduates were only 74% sure that America would remain neutral.

It was this same question which brought a dark cloud over the campus. The question, as phrased in the poll conducted jointly by the Pictorial and The Dartmouth, was: "What course of action for the United States do you favor? (a) permanent neutrality, (b) immediate entrance into the war, (c) shaping our policy in accordance with future events." Undergraduates favored permanent neutrality by a ratio of more than 92 to 1. Only nine students of the 1500 thought the United States should jump head over heels into war immediately. But on the other hand, there were four faculty members of the 100 who favored immediate participation.

In one class, a professor told his students that he was for immediate participation and inferred that every other redblooded American should also be willing to engage in immediate participation. To the class his statement seemed incongruous. He was in his 6o's; they were young with a lifetime ahead of them. They did not feel prepared to go to training camps where they would learn the art of bayonet warfare, where they would twist knife blades into sawdust dummies, smiling while they did it, where they would be preparing themselves for the groundwork of a war in which they felt no share.

Aware of the danger of over-stressing the point, we feel much would remain unsaid if the editorial in The Dartmouth of October 3d, entitled "Selfishness: Not an Admission, but a Faith," were not reprinted verbatim here, partially because it reflects the honest attitude of Dartmouth undergraduates, but primarily because it reflects the feeling of most of American youth. We quote:

"A professor of Dartmouth College stood up on the platform yesterday and told the men in front of him that they should be in the front trenches, killing Germans, that they were selfish to put their own lives first, that there were more important things than living.

"The professor won't ever have to go out to kill, or be killed, and we are deeply sorry that he felt it his responsibility to tell the young men in front of him that they should do so. We think he, and others who may think as he does, should try to understand just what the younger men mean by the attitude which he calls 'selfishness.'

"We are young, our lives are still ahead of us. The time we've spent so far, we've spent getting ready. We have things we want to do. We've not prepared for killing other people as a business and our futures we've always held as too important to cancel in bleeding over a barbed wire fence in Europe. 'Selfish,' perhaps. Call it that if you want to. We're proud of it, and glad that we live in a country where we can grow up that way. But there's more to our 'selfishness' than just that.

"We like America. We like the Democracy we have, and we've always held the ideal that we're going to college so that our democracy will be a better one. One thing we learned at college, that democracy doesn't last very long during a war, that it ends the moment war begins, but that, more often than not, it doesn't return when war ends. 'Selfish,' maybe, but we've been brought up in a tradition which held that our democracy was worth being selfish about.

"We're 'selfish' too, if living can be called selfishness, of our freedom, of our right to say what we believe, we're 'selfish' of our opportunities, of our institutions, of Dartmouth College, where all that is in the realm of knowledge and thought is ours for the work of taking. And history proves we're not wrong in believing that little or none of this can survive a war.

"And finally, we're selfish of life itself, not as a single thing, measured by the span of one man's existence, but of life as an entity, with its work, and fun, and hope, and promise, and improvement. And we do not believe that kind of life can be in a nation given over to the task of manufacturing death.

"If all this, in truth, is 'selfishness,' then it's the kind of selfishness which is not an admission, but a faith."

Just as surely as the youth of America was given a faith or an ideal to fight for in the last war, "Make the World Safe for Democracy," so should it give itself one when it is at the brink of what may become another universal catastrophe. We owe it to ourselves to make a faith and an ideal, an avowance to defend neutrality. It is an ideal to live for; there is no ideal worth dying for.

FRATERNITY RUSHING

Fraternities held a seven day period of party manners during the latter part of September and completed the week of rushing on a Wednesday. There was feeling of something counterfeit about the new system of rushing, and the induction ceremonies which most houses held on Saturday, following the last day of rushing, came as an anti-climax. There used to be a feeling of suppressed excitement and suspense in sitting in a dormitory room waiting for a cannon to be fired in the middle of campus—a signal of midnight, a signal to run to your new brothers, a signal that there was to be an important event which would take place in your college life.

The week of rushing began quietly and ended as quietly. Pledges were signed up quietly and inductions were quiet. Even the Saturday night parties were less noisy than they have been in a long time. Except for stray groups of rambling sophomores who toured the campus singing the songs of their patron fraternities, there was little external manifestation of pledge night that used to be. Internally, there was probably little difference: fraternities will always point with pride toward the brothers who are "doing things" on the campus; they will always list the advantages to be found in joining their houses—good-looking exterior, comfortable furniture, "largest bar and game room in town"; they will always put their best feet forward, listen attentively to potential pledges, smile at second-rate jokes, encourage pledgees to talk about themselves.

That is all part of fraternity life; it is an internal quirk and one that could not be changed without doing away with the fraternity system altogether. As long as one house is competing against its next-door neighbor for members, rather than having the administration pull names from a barrel like an army draft, there will always be the apparition of sham flying around in black shrouds overhead. But it would be inconceivable to throw out fraternities and the chaff must be expected in with the wheat.

This fallacy in the fraternity system appears inconsequential when placed alongside the changes which have been made in fraternity rushing from a mechanical end. Since Davis Jackson '36 stepped into the post of College Adviser to Fraternities, Dartmouth has seen an era of reformation in its Greek letter societies, partially through the work of Jackson and partially because of the efficient Interfraternity Councils he has had to work with.

Pledge delegations have been limited to 21 members and by 1940 there will be a maximum of 55 brothers in each house. This fall, for the first time, a limitation was placed on all fraternities as to the amount they would be permitted to spend on rushing. Under the present plan, no fraternity will be allowed to self-indulge beyond a $lOO budget. Still another change in the mechanics of fraternity rushing is that which compels all houses to treat potential pledges as freshmen if their scholastic standing for the preceding semester is less than 2.0.

These are but a few of the changes which are to bring Dartmouth's fraternities out of the Dark Ages, reformations which are aimed at reducing the societies to a more workable norm. Whether this objective can be accomplished, whether the large houses will no longer get fat on the cream, leaving the smaller houses nothing but the skimmed milk, is not yet clear.

By 1941, the value of fraternity restrictions should become apparent. If they do no good, Dartmouth fraternities may be in need of a greater and more rigid reformation.

PALAEOPITUS ASSUMES CONTROL OF STUDENT DRIVINGMembers of the senior governing body shown registering student cars and distributingdriving permits in an office in the College-owned Lang Building.

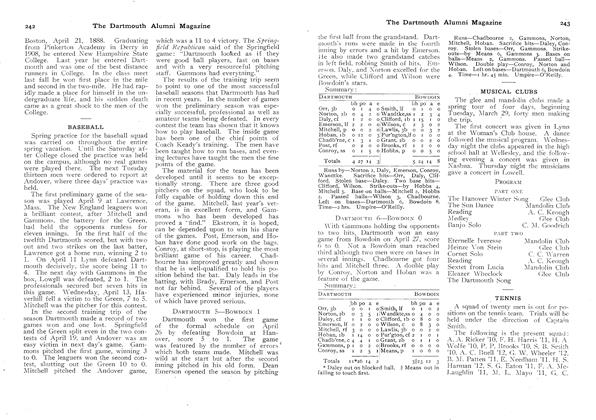

As THE HIKER SEES THE WORLD FROM MOOSILAUKEAn infra-red film view of the mountains to the northeast of the summit. In the foregroundis the winter cabin, never locked, a shelter in bad weather.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleA Humane Historian

November 1939 By FRANCIS BROWN '25 -

Sports

SportsBig Green Teams

November 1939 By Whitey Fuller '37. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1930*

November 1939 By ALBERT I. DICKERSON, CARL W. HAFFENREFFER -

Article

ArticleGRADUS AD PARNASSUM

November 1939 By The Editor. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1915*

November 1939 By CHARLES R. TAPLIN, NORVILLE MILMORE, Charlif1 more ... -

Article

ArticleThis Unwanted War

November 1939 By ALBION ROSS '29