March in Hanover, That Trying Transition from Winter To Spring, Conceded to Have a Few Compensations

THE IDES OF March have been with us and have gone in the way that the ides of March have been going ever since someone thought of the quote which covers the situation. The mane of the lion has been twisted and snarled by a lashing wind, cold weather, rain, sleet, and snow. But the lamb has been soft and fleecy; it would have been fleecy even had the lion been standing threateningly by, for Dartmouth has packed up its suitcases and has vacated Hanover. A vacation is every bit as good a pacifier to men who are finishing up the most dreary time of the year as all the balmy weather in the history of time.

(The only regret that the author of this column has is that a deadline compels him to write as if all this vacation were taking place as he writes; but it won't occur until you read. Meanwhile it is wishful thinking to write of a holiday in April as the March winds blow outside the window.)

March, in many respects, has its compensations. It is the month when everyone steps up a notch or is suddenly made »aware of the fact that he is about to move up. Juniors have gone through a period of fittings, and the chalk marks on the sleeves and backs of the junior blazers have been erased. The first sign of Spring in Hanover is not the robin but the first appearance of the new class jackets on the streets—that sign of Spring has already appeared, but it has also been the swan song of the seniors whose coats are no longer junior blazers but have become senior jackets. They are reminded that next year the coats will be neither, but will be referred to in the tone with which one speaks of the "old school ties."

But to many there are more important symbols of moving up.

Juniors sat in their rooms one night last week and waited for a knock on the door. It was the night of tapping for the Senior Societies and, to all those who felt that there was a good reason to prefer the quiet of their rooms to the second show at the Nugget, it was a period of anxious waiting. A step in the hallway brought a forced concentration on anything which might lead a society visitor into believing that the occupant of the room was not expecting company. There were many who didn't expect company that did come, and their names are now listed in one of the three societies; but there were others who did expect a tap on the shoulder whose names are not among those present.

Senior Societies offer a peculiar problem. There are very few men who do not entertain the idea of joining a fraternity when they enter as freshmen; but there are very few of them who feel that they will someday be taken into one of the groups, whether it be the Dragon, or Casque and Gauntlet, or Sphinx. As the years at Dartmouth move, the societies seem to increase in significance in the eyes of the undergraduates, until to some they become a symbol of all that is Dartmouth, which is an unfortunate conclusion since they represent only a little wedge Of college life.

But there was an election to prominent society recently which a large majority of each freshman class would like to make because every man knows that belonging to Phi Beta Kappa symbolizes a peak in his college life. The scholastic honorary society is more than a gold key swinging at the middle of a heavy watch chain somewhere below the third button of a vest. It is the fraternity you first heard about when you were called into the principal's office in high school to be reprimanded in what may have been a pedagogical voice—and probably was. He was the person who gave you the idea that Phi Beta Kappa was only a gold key on a corpulent stomach, because, as he spoke you couldn't take your eyes from the key which bobbed as he breathed; it had the hypnotizing force of Rasputin's twisting watch. But later you met another Phi Bete—he may have been your Uncle John or an old friend of the family. He was friendly with his intelligence; he thought, but it was not always book learning; he tried to go beyond the end of the books he read and would settle back and close his eyes while he tried to see what the next two hundred pages might have been.

And the same is true whenever an election is held to Phi Beta Kappa at Dartmouth. The aim of a liberal college is to educate the whole man, not to cook him thoroughly on one side, represented by book learning, and leave him raw on the other, made up of applying his learning to life and of living with his learning. It would be almost impossible to revise the requirements for the scholastic society in order to make them conform to the man who has been educated from all sides. But something ought to be done, if only to insure that there are more men on Phi Beta Kappa like our Uncle John whom we like a lot more than the gold key swinging on a pedagogical stomach.

Plans are afoot to revive the College Chest which Dartmouth has not seen since the early days of the depression, way back when prosperity was just around the cornel In 1924 the Community Chest drive netted almost $4,000 which was distributed among local agencies, although some of it went as far as Belgium to aid in the reconstruction of the Louvain University Museum which had been destroyed in the war. The chest continued on without falling below the 1924 level and, in a few of the years prior to the crash, shot over the $5,000 mark. Then, just as Hanover needed aid more than ever, the drive fell flat on its face, to lie there unattended until Palaeopitus recently proposed revival.

Acclaim for the plan has been cordial among townspeople and faculty members who were queried as to their reactions. Though the student body has had no opportunity in the form of petition or questionnaire to speak for or against the chest, there is little doubt that undergraduate reaction is favorable. The outstanding reason for Dartmouth's favoring the Community Chest is that it will concentrate all appeals into one period and eliminate scattering them throughout the college year, which serves to dissipate student resources.

In answer to what it believes may be the reply of a handful of students, who may object to a drive for funds in a town in which they feel no interest, The Dartmouth stated:

"The resources of the Dartmouth student body are virtually untapped for charity. That is bad for the students who get in the habit of confining their humanitarianism to boos and noble sentiments and not kicking dogs, and bad for the society in which they live without helping the needy A well-conducted community chest drive would increase the amount available for charity work and provide a framework to systematize and coordinate the Hanover charities. It would bring the students into the Hanover charities picture. It should go far toward relieving the three shortcomings of Hanover charitylack of funds, lack of organization, and lack of student interest."

There's a warning in The Dartmouth's editorial. It was a lack of efficient organization, coupled with the depression, which defeated the chest in 1931. We are beginning to worm our way out of the depression today but the danger of poor administration is a threat in good times as well as bad, although it may not be quite so obvious.

Before the Community Chest can become a real and helpful force in Hanover life, its stability and efficiency must be insured. Dartmouth undergraduates ask only one thing of Palaeopitus before the proposed drive is put into effect. It asks that the investigation not stop with the recognition of the fact that the Hanover community charities are in need of money, but that it go further and determine the best way to organize a working method which will continue to do what it sets out to do.

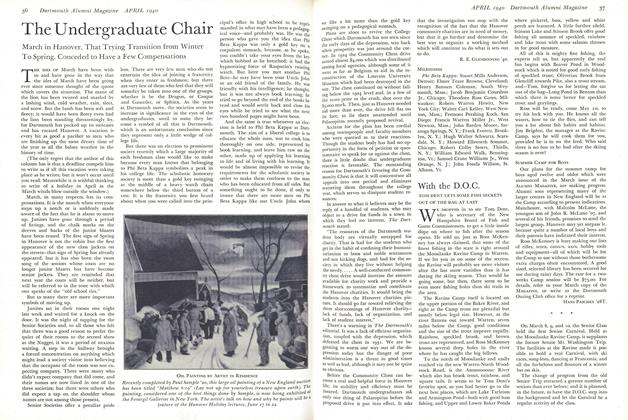

OIL PAINTING BY ARTIST IN RESIDENCE Recently completed by Paul Sample '20, this large oil painting of a New England auctionhas been titled "Matthew 6:19" (Lay not up for yourselves treasure upon earth). Thepainting, considered one of the best things done by Sample, is now being exhibited oXthe Ferargil Galleries in New York. The artist's talk on how and why he paints will be"feature of the Hanover Holiday lectures, June IJ to 22.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleRich Man's College?

April 1940 By JOHN HURD JR '21 -

Article

ArticleMeet Bill Daniels—

April 1940 By CHARLES E. WIDMAYER '30 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1930*

April 1940 By Chairman, ALBERT I. DICKERSON -

Sports

SportsBig Green Teams

April 1940 By Whitey Fuller '37 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1925*

April 1940 By Chairman, FORD H. WHELDEN -

Class Notes

Class Notes1938*

April 1940 By Chairman, CARL F. VON PECHMANN

R. E. Glendinning '40.

Article

-

Article

ArticleA Wah Hoo Wah for –

January 1960 -

Article

ArticleA Dartmouth Family Portrait

MARCH 1989 -

Article

ArticleCrossing the River

MARCH 1994 -

Article

ArticleGive a Rouse

May/June 2010 -

Article

ArticleThayer School

December 1951 By Davis, Fred R. '95 -

Article

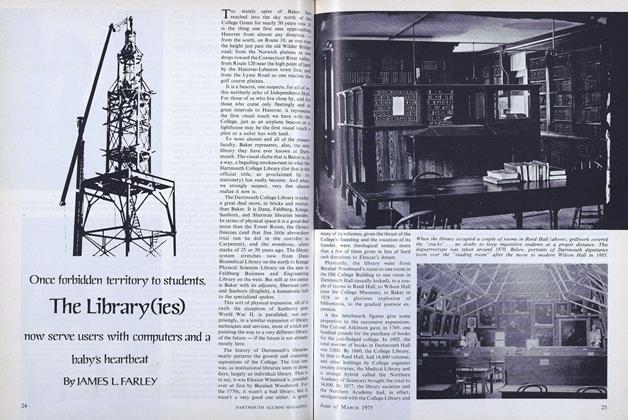

ArticleOnce forbidden territory to students, The Library(ies)

March 1975 By JAMES L. FARLEY