The Versatile Career and Interests of Frank Maloy Anderson Scholar in International Affairs and Noted Teacher

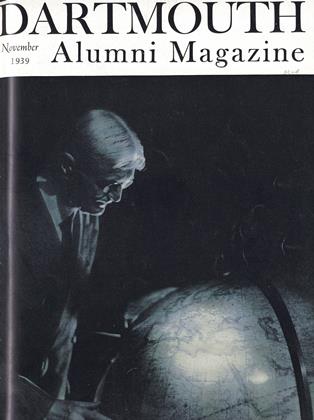

ON the Dartmouth campus, in the classroom and on the playingfield the tall, spare figure of Frank Maloy Anderson has been familiar for a quarter century. Over the years his hair has whitened and the lines have deepened in his face. No longer does he stand quite so erect. Yet at 68 the eyes behind the pince-nez have not lost their brightness. Frank Anderson remains, as when he first addressed a group of Dartmouth undergraduates, the scholar and the teacher vigorous, able to inspire the serious and to pound into unwilling heads the rudiments of history.

It was in September, 1914, after many years at the University of Minnesota, that he took up his teaching on Hanover Plain. The World War had just begun, and though the Germans had been turned back at the Marne and the Russians overwhelmed at Tannenberg, the lines were not yet fixed nor the course the war would follow yet apparent. European history had suddenly taken on new meaning, a significance that for most Americans it had never held, and it was European history that Professor Anderson was to teach at Dartmouth.

That first winter, while Russian and Austrian were battling on the Carpathians' snowy slopes and German faced Frenchman and Briton along the dreary miles of trenches in the West, a group of students asked him to organize a course in World War history. Of necessity it could be hardly more than current events, but it drew fifty-two men for what may have been the first World War course in any American college. A long road had opened down which Professor Anderson was to travel, for he was to be at the Paris Peace Conference and was to be teaching World War history for a quarter century, enlarging, revising, reshaping his lectures as year after year documents and interpretations have come from public archives and scholars' typewriters.

In the Nineteen Twenties, when historians focused much of their attention on the World War, and particularly on its causes, Professor Anderson was among those who had small sympathy for contentions that French or British or Russian responsibility for the war's coming was as great, perhaps greater, than that of Germany. His defense of France, for instance, led him into scholarly controversy, but he stood his ground, even when most of his Dartmouth colleagues, openly or secretly considered his views, if not wrong, at least extreme.

The war-guilt question receded, and by the time Adolph Hitler came to power in 1933 had been almost forgotten. Now there was a new controversy—the Treaty of Versailles, the "dictate" to whose harshness many who could not be called apologists for Germany attributed much that had happened. Professor Anderson has never been among them. He recognized, of course, that the treaty was not easy or its burden light, but he went somewhat deeper in explaining Nazi Germany, finding its roots in the November, 1918, military defeat that brought down in ruins German hopes and all the proud accomplishment of the decades after William I was proclaimed Emperor in the Hall of Mirrors at Versailles.

That blow to national pride, Frank Anderson maintains, engendered what might, for lack of better term, be called a national tional inferiority complex that the tragic post-war years made only worse. In such an atmosphere the teachings of Adolf Hitler flourished until on the night of Jan. 30, 1933, the Nazis marched through Berlin in a torchlit procession of triumph. Adolph Hitler was Chancellor of the Reich, and post-war Europe had entered upon a new phase.

As Professor Anderson looks back on all this today, he feels and believes, as do many with him, that the rise of Hitler and his Nazis need not have meant war had not the European statesmen who confronted the Third Reich been afflicted with an astigmatism that marred their vision. Almost blind—some would use the word stupid—these statesmen compounded each mistake. Blunder followed blunder from the time Britain's Foreign Secretary, Sir John Simon, by refusing to cooperate with Henry L. Stimson, the American Secretary of State, permitted the Japanese in 1931 to win their Manchurian adventure, thus setting a precedent for aggression in disregard of treaties and international understandings.

The fiasco of sanctions in the Ethiopian war, Hitler's rearming of the Germans and the remilitarization of the Rhineland, British naval concessions to Germany, the Spanish civil war, Austro-German Anchluss, Munich—these were headlined blunders. All contributed to the making of a more powerful, more arrogant Reich, and aided simultaneously in lowering the prestige of Britain and her French friends across the Channel. When at last the French and British Governments were ready to make their stand, it was, at least in Professor Anderson's mind, almost too late.

He talked about the European war a few weeks ago, on a September Sunday when the Hanover air tingled with Autumn crispness and Balch Hill was freshly crimson and gold. The war was still young, but Poland had already been crushed and the Russian enigma remained unsolved. He was depressed by the outlook, he said, for so far as he could tell the Germans had a fifty-fifty chance of victory, and victory could mean only one thing—a Hitler-dictated peace. To him such a peace would carry, not only German domination of Europe, but, inevitably, German control of the seas, with all such control would signify for world trade and, above all, for a United States long accustomed to working and living with the "Pax Britannica."

The possibility of German victory so alarmed Professor Anderson that he had small patience for the prevailing American desire to keep out of Europe's war. He felt, and said, that the United States, every man, horse and gun, should be in the conflict on the Allied side, ready to make certain that the Swastika would not wave over Buckingham Palace or the Elysee.

MINNESOTA BOYHOOD

His alarm, moreover, was mingled with a sense of hoplessness for what might lie ahead in Europe. This question was put to him: What chances are there, once the war is over, for the European stability needed to rebuild civilization along the lines the Western nations accept as fundamental to their way of life? He saw none. The exigencies of the situation would dictate, probably, a repetition of past mistakes. Only in a Hitler-dominated Continent would there be much likelihood of stability, and that brand would not bring a renaissance of Western civilization. Rather would it bring a new order whose outlines six years and a half of Nazi Germany have perhaps only dimly suggested.

It was not a pretty picture, nor one that all would accept, but it was what Professor Anderson foresaw. It reproduced the impressions and conclusions born of long study, observation and experience that are worth recalling.

Frank Anderson was a Minnesota boy, and one whose boyhood and youth were none too easy. Fatherless at 10, he knew early what it was to peddle newspapers, deliver telegrams, or work as an office boy. His schooling was interrupted. Never had he the opportunity to read as widely as he would have liked or as much as do most boys. Yet eventually he entered the University of Minnesota and in 1894 received the bachelor's degree. Except for intervals of study elsewhere, he remained at Minnesota until called to Dartmouth.

That is the story in brief, but it is not the whole story. As a boy he had the same zest for living and learning, the same keenness of observation, that he has today. Most of what he saw and learned as a youth he has not forgotten. It all counted toward an understanding of life and of human behavior.

Early Frank Anderson was caught by history's fascination. He likes to believe now that the fire was set in the Minneapolis Athenaeum when, still very young, he turned the pages of the Civil War volumes of Harper's Weekly. However that may be, the fire was set, never to die down.

Over the years he has spent many hours in personal examination of yellowing documents, of dusty newspaper files in libraries far removed from Hanover. It has meant close association with the stuff of which the historian builds his lectures and solid monographs, and it has provided the knowledge that gives both lecture and classroom discussion weight, conviction.

Herein lies some of the Anderson philosophy of teaching, though he would be the last to dignify his methods by the term philosophy. He has always believed that a teacher should saturate himself in his subject, know its many twists and turnings, its lights and shadows. Filled with the what and the why, he should then be able to stand before a student group and present the product of his efforts. There are no set rules, no fixed formulae, for teaching is a subtle thing that defies regimentation. A chance phrase thrown out almost unconsciously may illuminate a problem that has eluded student solution. What inspires some, bores others. What leaves one man unmoved, excites his fellow to labors far beyond the course routine.

IMPORTANCE OF RESEARCH

Such teaching, Professor Anderson believes, is unlikely with the man whose knowledge of his field is at best only superficial. It comes ordinarily from one who has not been content merely to keep abreast of the stream of his subject's literature, but who has gone to the very foundations through research. To Frank Anderson research must be the handmaiden of teaching. And what is research? He offers this definition: Continued study, long after the formal studies for graduate degrees have ended, the study that keeps a scholar alive, alert, aware constantly of how historical events occur, how they are shaped, how they influence each other, how they fix the careers, even the personalities, of the men and women whose lives loom large on history's pages.

There is a school of thought, and it has been present at Dartmouth as well as other colleges, that contends research and teach.ing are incompatible, that argues the tedium of research dulls the keenness of the teaching mind. Professor Anderson gives that argument short shrift. Good researchers, he admits, may sometimes be bad teachers. Good teachers may sometimes be bad researchers. But these are exceptions, perhaps the exceptions that prove the rule. On that he stakes his reputation, and so he insists: "Put me down as one who believes in research as a prerequisite for the best sort of teaching."

Not all knowledge, of course, is to be gathered from books or archives. Some comes from association with other scholars. For more than forty years Professor Anderson has been active in the American Historical Association, attending its annual meetings, talking and swapping experience with members young and old. To him the meetings—and at them have appeared leaders in American historiography like Turner and Hart, Oberholtzer, Beard, Robinson and many others—have been an inspiration that has sent him back to Hanover filled with renewed zeal for the work before him.

Knowledge comes also from observation. It may be the observation of a party convention or a political campaign. It may be observation born of participation in some great event. Professor Anderson's part in the making of the Versailles treaty illustrates the point.

His was only a small part, he quickly cautions, adding that he, like most of the experts who gathered in Paris in the postArmistice months, knew actually little of what went on. "We had a sense," he recalls, "of being close to the making of history and yet never actually seeing history made." Perhaps the nature of his work at Paris is better told in another's words. James T. Shotwell of Columbia, organizer of a staff of experts to aid the American Peace Commission, tells some of the story in his diary, "At the Paris Peace Conference."

The first entry that mentions Professor Anderson is a sort of footnote to the diary's record of Jan. 19, 1919: I had been short handed in diplomatic history after all, and had succeeded in having Professor Frank Anderson, of Dartmouth College, cabled to join me and take over that part of the Division of History. I had a personal satisfaction in this, as Anderson worked with me in the summer * * *. Other entries, typical, follow: Jan. 23, 1919: Professors Anderson and Notestein arrived with messages from New York. Anderson * * * and I spent the morning * * * planning work. Jan. 24, 1919: Work with Anderson in the morning; the Division of Diplomatic History gets under way. Jan. 28, 1919: Anderson and I at diplomatic history and some dictation. derson for reports for one of the Commissioners.

There were interludes in the work, with trips to the battlefields, long walks about Paris, where war's shadow had not been wholly dispelled, and then, ultimately, the real work of framing the statute for the International Labor Organization. It was the chief task on which Professor An- derson was employed.

None could then foresee that the statute, twenty years later, would promise to be the most permanent accomplishment of the peace-makers, and as Professor Shotwell, Professor Anderson and others went about their work at the Ministry of Labor, meeting in a magnificent room that once had been the chapel of the Archbishop of Paris and that rumor erroneously said had been still earlier the banqueting hall of Madame de Pompadour, there were times when it seemed the statute could never be drafted. Drafted it was at last, to become Article 405 of the Treaty of Versailles.

Professor Anderson, as winter merged into spring, left Paris to teach at the Army University in Beaune, a somewhat grandiose project for keeping the American soldier occupied pending his return home. It amounted to little, and by June Professor Anderson, "looking like a bronzed veteran," Shotwell reported, was back in Paris. That fall he took up teaching again at Dartmouth.

Such experience helped to make of history a living thing. Never again for any who worked at Paris would the teaching of diplomatic plot and counterplot be merely a matter of books and papers. All was close, personal. To a degree, at least, there was something of the Virgilian: "Allof which * * * I saw, and much of whichI was." Here indeed had been an exercise in source material for the courses in diplomatic and World War history that Professor Anderson was to make so popular with Dartmouth men in the years after Versailles.

Not all the Anderson classroom discussions and formal lectures that have kept the college generations trooping into Wentworth or Reed, that in a quarter century have drawn more than 3,000 students, have dealt with the war or its diplomatic background. Some have looked at Europe's troubled post-war years. Others have turned back to the French Revolution and the century in France that followed Waterloo. All have been characteristically Anderson, delivered informally enough for student questioning, delivered slowly with that definition-defying mannerism that is neither drawl nor stammer nor yet wholly deliberation. All are presented in the orderly fashion that delights the student notetaker. All have the ring of authority.

The contemporary tendency among historians is specialization. A man becomes an authority on the Middle Ages, diplomacy, American politics or social trends. But Frank Anderson has been inclined to make all fields his own, and if he has specialized, it has been in regard to his political approach at a time when new viewpoints have emphasized the social or economic. Despite this checkrein, he has ranged widely, and here may lie partial explanation of his failure to contribute more to historical literature or to capitalize to the full his abilities and knowledge.

At Dartmouth his formal courses have been in the European field, but long ago, at Minnesota, the constitutional history of mediaeval England seemed important enough for a volume of relevant documents to be edited at the Anderson desk. Catholicity is reflected in much that Professor Anderson has written for the American Historical Review and in the papers he has read before the Historical Association's meetings. Some have been concerned with French history, some with European diplomacy of the pre-World War era. Many have dealt with American history, and often its somewhat obscure chapters. As he looks forward to retirement, he hopes there will be time for the writing of a major work on the outbreak of the American Civil War.

INCREASED LIBRARY COLLECTIONS

Another aspect of this breadth of interest was demonstrated during Professor Anderson's five-year term as chairman of the faculty library committee. The post called for considerable routine work, but the routine was overshadowed by his efforts in building up the library's collections in history. Always attracted by the problems of bibliography, he now spent hours each day carefully checking the library's catalogue against items in secondhand book catalogues from all over the world. Recommendations for purchase resulted, and over the Anderson term volumes of documents and memoirs, of ancient treatises and modern studies increased steadily on the Baker Library shelves. In the end, although no such work could ever be complete, the collection had become notable among American college libraries. It was a contribution in which Professor Anderson takes a good deal of pride.

The college generations that have known Frank Anderson and his work, or have known him only as a figure beneath Hanover's elms, have thought of him first and last as a scholar and teacher. Few have heard of his generosity or have realized the independence of spirit that has kept him a Democrat in a Republican community. Fewer still have known his lighter side that finds pleasure in such frivolities as the lyrics and melodies of Gilbert and Sullivan, for he is, after all, a bit of the ascetic, neither smoking nor drinking, his chief vice a passion for coffee, consumed in quantity according to his own rule that two cups may keep one awake nights but three never will. But no student who ever watched Dartmouth baseball, basketball or football has failed to appreciate that in Frank Anderson, scholar though he might be, the Dartmouth teams had one of their most loyal rooters.

THE PERENNIAL WEEKENDER

Among his colleagues in the history department there is a long-time joke that, when the Dartmouth eleven is about to play Harvard or Yale, he suddenly recalls a document in the Widener Library at Cambridge, or the Sterling Library in New Haven, that needs attention. Thereupon off he goes for his research, completing it in time to appear in the stands before the starting-whistle blows, remaining until the end, regardless of rain or snow or November wind.

He laughingly admits this liking for sports. Baseball has been a game for him ever since, as a boy, he sold score cards and rented cushions in a Minnesota ball park. As for football, that too has been an enthusiasm since youth. He enjoys telling about his first game. He had never seen football when he was persuaded to join a scrub team. The rules were explained. The teams lined up and play was called. Frank Anderson never knew quite what happened then, and with good reason. Opposite him had been "Pudge" Heffelfinger, later the famous Yale guard and rated by some, the greatest player in football history.

Professor Anderson's loyalty to Dartmouth teams is paralleled by loyalty to Dartmouth as a college. When he came to Hanover in 1914, he was drawn in part by belief that he would find an institution that combined the qualities of a college and a university. He has not been disappointed—he gave two sons to Dartmouth —although he has sometimes wondered if the college has made the most of the opportunities within its grasp.

What he feels about the College is illustrated by his remarks on Orozco's controversial murals, remarks that also illustrate his strong opinions and tempering tolerance. He does not like the murals, for to him they present a wholly unjustified indictment of American education and American civilization. He does not regard them as great art, and was once reported to have said: "The American Baedeker for the year 2000 will triple star the Orozco murals as an example of the degradation of American art in the early twentieth century." "In this controversy," he insists, "there are no neutrals." Then he adds, almost as a tribute to the College and its philosophy: "Those frescoes prove at least one thing. At Dartmouth thought is free."

TWENTY-FIVE YEARS OF TEACHING Frank Maloy Anderson has been the leading authority of the department of Historyon Central European affairs for a quarterof a century.

The Europe of 1914 was divided mostly among the great powers with strong rivalries andembittered relations finally forcing the catastrophe of the World War. Radical changesresulted in the map of Europe.

After the War new states were created in Central Europe, Germany lost territory andpopulations, Russia was pushed back into the east. The map of Europe today is changing rapidly, with new frontiers drawn by Hitler and Stalin.

NEW YORK TIMES

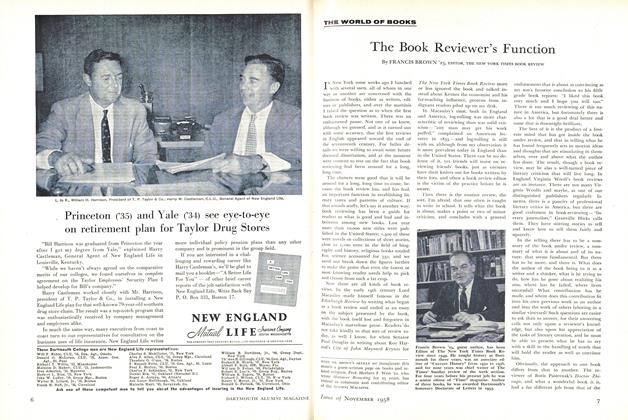

THIS IS THE SECOND of a series ofbiographical sketches to be published monthly during the year, describing the lives of members of thefaculty now at the height of theircareers and influence in the College. Francis Brown '25 (Columbia M.A. '27, Ph.D. '3l), author of the biographical sketch of Professor Anderson, was a member of the faculty in the department of History of the College 1926-39. He was subsequently associate editor of the magazine Current History and has since been a staff writer for the New YorkTimes. Mr. Brown edits and largely writes the "News of the Week in Review" pages in the Sunday Times. His roommate in New York is Ralph Thompson '25 whose literary comments appear daily in the Times' column: "Books of the Times." Shepard Stone '29 is also a staff writer and is editor of feature articles in the Sunday New YorkTimes.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Sports

SportsBig Green Teams

November 1939 By Whitey Fuller '37. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1930*

November 1939 By ALBERT I. DICKERSON, CARL W. HAFFENREFFER -

Article

ArticleGRADUS AD PARNASSUM

November 1939 By The Editor. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1915*

November 1939 By CHARLES R. TAPLIN, NORVILLE MILMORE, Charlif1 more ... -

Article

ArticleThis Unwanted War

November 1939 By ALBION ROSS '29 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1928*

November 1939 By OSMUN SKINNER, BRUCE M. LEWIS

FRANCIS BROWN '25

Article

-

Article

ArticleDEBATING LEAGUE MEETING

November, 1908 -

Article

ArticleDINNER TO "D" MEN

-

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH ALUMNI ATTEND HARVARD BUSINESS SCHOOL

FEBRUARY, 1927 -

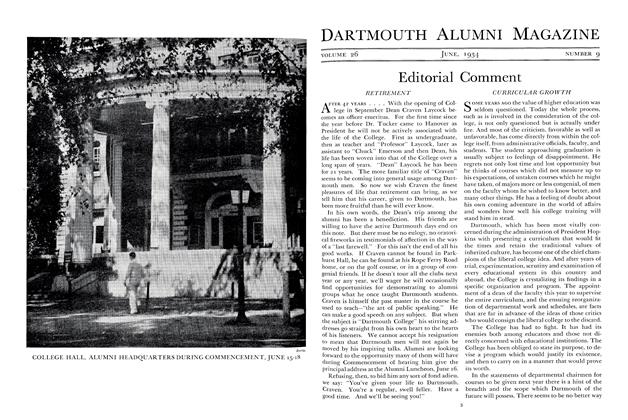

Article

ArticleCOLLEGE HALL, ALUMNI HEADQUARTERS DURING COMMENCEMENT, JUNE 15-18

June 1934 -

Article

ArticleAlumni Fund Cups

May 1942 -

Article

ArticleThayer School

April 1950 By William P. Kimball '29