Dartmouth Night Makes Student Body a Unified Whole; German Student Brings Contrasting View of Education

DON FOX, speaking for Palaeopitus at the 1939 version of Dartmouth Night, predicted that at some point during the program every man in the audience would get a tingle up and down his spine, a thump in the chest, or a quiver on his lips. Perhaps it was stubbornness on our part which made us determined not to have our reactions to speeches, perhaps filled with abstract words, predicted before hand.

We attributed the chill in our spines to a draft that was coming under a crack in the door at the back of Webster Hall when President Hopkins spoke; our gooseflesh, which came co-incidentally with the reading of the alumni telegrams by Dean Laycock, couldn't have been anything else but that same draft—so we thought. But it was sheer rationalization. We knew that even before the band started to play. We were convinced when Dean Laycock told of the last message sent by Bob Chase '3B, from aboard the ill-fated Chinese junk, "The Dragon."

But it wasn't a positive fact and a mental conclusion until we looked around crowded Webster Hall; looked up into the balcony and along the rows, down the aisles, and up on to the speakers' platform; saw every man singing the songs or, if he wasn't sure of the words, humming them or whistling them. Sitting alongside of us was a man from Massachusetts; he sang with a broad "A"; across the aisle was a soft Southern accent and a harsh one from the mid-West; two Japanese students, both freshmen, knew the words to the songs, were singing, while someplace in the hall was a Chinese student who knew the same words and was singing in harmony.

There was a league of nations in Webster Hall but, unlike its big brother, it really worked; everyone got together.

From Munich to Dartmouth comes Hans Froelich who entered College in the class of 1941. He's a tall dark-haired boy who speaks faultless English, as yet undiluted by campus cliches, American slang, and dormitory jargon. His background, though different from that of the average undergraduate, is exactly what makes him as valuable a part of Dartmouth as the boy from Kansas City who rooms with us, or the man from Baltimore who sits next to us in a Sociology class.

Hans' father is dead; his mother, part Jewish, lives in Germany. Last summer he worked in the Hanover Inn painting on the walls, but he wasn't doing murals. He just slapped three coats of white paint on a cellar wall with a four-inch brush. But he has some definite ideas on Dartmouth and its curriculum.

To understand his viewpoint it's necessary to understand some of his own educational background. German schooling entails four years of grammar school and eight in high school, as opposed to the American system of eight in grammar grades and only four in the other department. Through the eight of high school, through eight years of Latin and five of Greek, through rigid examinations in which all students sit spaced equal distances apart and each man wears a black suit-that is a rough idea of his formal education. His informal education began the day that he could understand his first German word and his parents began a home tutelage program, a tutelage which continued through the years of his formal education and won't stop until he becomes a parent and passes his informal education along to his children.

The chief difference that Hans, whose name, translated into English, means "Happy," finds between the American and German systems of education is that German universities and the preparation for them are more highly specialized, with each man knowing exactly what he wants out of college before he enters. In America, Hans estimates, 70% of the student body goes to college for the sake of going to college, perhaps because their parents want them to go or because it seems like a nice way to "meet the right people." "Because the American student doesn't know what he wants out of his schooling, he spends a lot of his time fooling around until he makes up his mind," he says.

GOES TO COLLEGE TO BE EDUCATED

The German youth feels much more educated than the American primarily because he goes to college to be educated. He does not feel that the day he enters college is the day that his education begins, nor does he believe, as many Americans do, that when he is handed his sheepskin after four years of schooling in a college, that his education is now completed, and that he is indeed a well-rounded young man. But the German youth's education goes even deeper than that; he does not go to college to learn how to behave and how to live with others. This is an attitude which the young German finds it hard to understand. "Learning how to act and how to adjust one's self to society is strange to the average German. Both are things one learns at home; neither can be taught in a series of lectures," he says.

Probably of greatest interest to an American is the play of present day Germany on that nation's educational system. Surprisingly enough, Froelich does not believe that it has had any effect at all as yet. "Education and culture are hard to affect by political boundaries. Though Catholicism may not be approved of in some quarters, families will continue to pass it on to their children. At one time, Art was affected by the Nazis and writing which seemed antagonistic to Germany, was done away with but even that to some extent has changed. Goethe in some of his works was not altogether nice to Germany and his writings were banned. But the Government has taken an objective viewpoint." He explained the present attitude is to allow Goethe to be read, on the grounds that he was a German and, regardless of his views, wrote some of the world's best literature which the German people should read. The Nazi government is anxious that its people should know the works of their best authors.

Nazi objectivity has gone even further than that however. Despite the war in which it is now engaged with England, Shakespeare's plays were on the boards of Berlin theatres at the time of the outbreak, which offers an instance in which national borders present no barriers to great literature. Naturally, that barrier is still there for any art forms which smack of Jewish influence.

FRATERNITIES SURPRISE HIM

The Dartmouth fraternity system was another surprise to Hans Froelich, with the greatest surprise centered on an egg-throwing battle on Main Street which one house had their pledges stage. The German universities have their fraternities but, for the large part, none of them are Greek letter societies such as the ones to which Dartmouth is accustomed. Their names are taken from German history and mythology and go under the names of co-operations. Each fraternity has its own colors, its own uniforms, its own songs and its own small cliques.

That was five years ago. Today, Germany still has its fraternities in the universities. They go under the name of the N.S. Studenten-Bund, with the Bunds divided into fellowships, a fellowship to a university; modern German fraternities have their own uniforms and colors too they wear brown shirts. Whereas the former German societies had a great liberality of thought whose objective was merely "liberality of thought," the modern society has equally as much liberality; their members are still permitted to think as they wish. But there is a difference—present day fraternities must use their thoughts for the good of Nazi Germany.

Though Hans has not been a Dartmouth undergraduate long enough to be imbued with the Dartmouth spirit in the sense that most of the College's sons know it, he has gone through emotions which he doesn't quite understand but which most Dartmouth men could explain to him. When the score of the Harvard-Dartmouth game was announced on the radio, he was in Concord. The announcer blared a Dartmouth victory. Hans said he felt all tingling inside and his stomach had a warmth. He was sure of one thing—he was proud to be a member of Dartmouth College.

Hans doesn't know yet that the Dartmouth spirit, which is mentioned often in print but is never defined, has something to do with warmth in the stomach, a tingle, and a feeling of being proud. He'll find that out in time. He'll find out when he sits in on another Dartmouth Night, looks around the room and sees students from all over the globe singing, humming, or whistling, the same songs, a few of them off key but all shooting at the same tune.

MILESTONES:

1940 Phi Beta Kappa: Richard Felt Babcock; Keith Stone Benson; Chester Ridlon Berry; William Dewey Blake; James Gray Buck; James Dana Darnley; Walter George Diehl; Lawrence Rogers Gordon; Jack Waldmar Hannestad; Daniel Lester Harris III; Robert Starr Kinsman; Judson Stanley Lyon; John Harold McMahon; John Thompson Moffett; George Thompson Mills; Jack Joseph Preiss; Owen Arthur Root; James Lewis Schaye; Kenneth Clark Steele; Joseph Samuel Sudarsky; Seymour Edwin Wheelock.

SPHINX: Thomas Arthur Ballantyne Jr.; William Lyman Huffman; James Herbert Young.

CASQUE AND GAUNTLET: Eldon Eugene Fox; Scott Arthur Rogers Jr.

DRAGON: Robert Ellis Dibble; Robert Hamilton Dingwall; Richard Ferebee Kenney; John Edward Dean Peacock; Arthur Means Pollan.

TOUCH FOOTBALL FINAL ON THE CAMPUS The Class of 1940 team, winner of class competition, shown defeating Kappa KappaKappa, interfraternity champions, for the intramural football crown of the College.

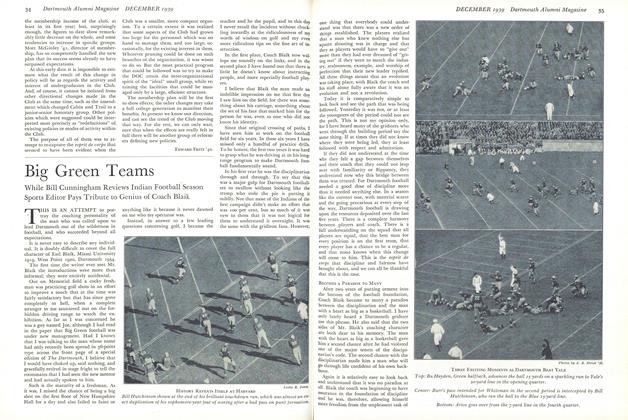

THE BAND GOES COED John G. Moody '40, in back taffeta, andWilliam B. Hammond '41, in tails, haveprovided terpsichorean antics between thehalves of the Dartmouth football gamesthis fall. Moody, manager of the Band, isthe son of the late Howard G. Moody '09;and Hammond, assistant manager, is theson of Karl R. Hammond '09.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Sports

SportsBig Little Green Team

December 1939 By BILL CUNNINGHAM '19 -

Article

ArticleHe Makes Students Think

December 1939 By HERBERT F. WEST '22, ERIC P. KELLY '06 -

Article

ArticleA Landmark Is Gone

December 1939 By WILLIAM A. ROBINSON, Robert Lincoln O'brien '91 -

Article

ArticleGRADUS AD PARNASSUM

December 1939 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1931*

December 1939 By CHARLES S. MCALLISTER, CRAIG THORNE JR. -

Sports

SportsBig Green Teams

December 1939 By Whitey Fuller '37

Richard E. Glendinning Jr. '40

Article

-

Article

ArticleTHE TOPLIFF BEQUEST

January, 1912 -

Article

ArticleTHE FIRST TWO DARTMOUTH COLLEGE TRAINING DETACHMENTS

November 1918 -

Article

Article1951 Is Living Up to Expectations

March 1948 -

Article

ArticleDartmouth at the 14th Snoopy Tournament

OCTOBER 1988 -

Article

ArticleSelective Admissions

APRIL 1994 -

Article

ArticleMedical School

MAY 1973 By BLISS KIRBY THORNE D'38