The "Fighting, Crying Eleven" of 1939 Makes History Despite Lack of Reserves, Material, and Experience

WHAT'S that line in Shakespeare about how it's not so deep as a well, nor so wide as a church door, but it's enough and 'twill do?

That would take care of the 1939 Dartmouth football team even if it had lost every joust on its program, but what are you going to do about a team that looks like practically nothing on paper and still takes such an active interest in its own assassination that it not only sends the enemy flying in almost every contention but all the experts with them?

You gentlemen at a distance may not realize that Dartmouth lost to Princeton, and then by two mere points in a free wheeling tussle that could just as easily have been a 7-3 Dartmouth victory, just in time to keep the New England football experts from having to decamp en masse for points plenty far and on a one-way arrangement.

The strangest part of it was that the critics really were right when they said this Dartmouth team was little and lacked talent and was far too shy on man power. Graduation, removing such stalwarts as Bob MacLeod and Bob Gibson, had whittled it down to the nub. Two lean freshman teams, more truly representative of the Aristocracy of Brains than the Democracy of Brawn, hadn't delivered the requisite replacements. And the luck of the draw had ironically arranged it so that this diluted unit faced the. formidable task of struggling through a schedule that would have taxed the powers of one of those man-killing teams.... say the one of 1936.

Their assignment started with a couple of soft touches, as the boys say, the names of same being St. Lawrence and Hampden-Sydney. Don't ask me where they get 'em. It's the good old Army way. But from there, the list ran: Navy, Lafayette, Harvard, Yale, Princeton, Cornell and Stanford, with every game, but Lafayette and Cornell, on an alien field, meaning travel.

For this Dartmouth had three seniors, or more properly two and a half, for Captain Whit Miller, the end, a whizz his sophomore year, but a little slower if smarter last season, was possessed of a treacherous knee, hurt not in football but in skiing, which figured to sideline himand which promptly did. These are what the coaches had—these and a lot of little guys named Joe.

The eastern scribes like the current Dartmouth coaches and they started weeping for the Green in print as far back as the middle of the summer. By the time the season began, everybody had the handkerchief out and practically the greatest flood since Noah's was all over every sports page. And I still insist, it was Christian, charitable and sincere literature.

Starting with Navy, Dartmouth figured to become murdered every Saturday. Lafayette is no cream puff in this day and age in case you haven't been listening. The rest you're probably familiar with.

Dartmouth had one back of any known ability. That was Bombshell Bill Hutchinson, but Bill is a bombshell; he's no tracer bullet. His forte is carrying the football, and kicking the football, and, as it has since developed, passing the football. But he didn't figure to go anywhere without somebody to block for him, and there were no blockers to be had. Furthermore the New York speedster wasn't much at throwing blocks for somebody else. That didn't make sense, anyhow, for if he blocked, he couldn't carry, and if he didn't carry, who could?

The coaches had been hoping for two years that a fellow named Bob (Blitz) Krieger could. He came on from Minneapolis with a terrific reputation as a halfback, and last year the coaches had him subbing for MacLeod. They insisted when asked that he really wasn't a good halfback. They said he didn't have the knack of "running the routes." (It's considerably different from what it was when you and I were young, Maggie. On those deep reverses and such, it's the matter of running a curved line on split-second timing, of cutting just so and "exploding" at just the proper place.)

We thought they were fooling about Krieger, that they were keeping him under cover, and that when time came to rip the wraps off him, he might even out-MacLeod MacLeod.

But after him, there was practically nobody. Courter and Norton, the two blocking backs, officially listed as quarterbacks, were there last year. Neither, with all due respect to them, had been Grade A performers. Sandy Courter looked great as a freshman, but he hurt his knee badly in spring practice his freshman year, and it slowed him up just enough to make what seemed a sadly permanent difference between good and fair.

There was a fullback, a 175 pounder, named Jim Hall. There was a substitute halfback named Hayden, wearing the nickname of Cowboy, who'd been around but who simply didn't seem to have what it took! Each year he'd have one great day, usually against someone of those little first or second gamers. After that, he had the fatal habit of losing ground on end runs. He'd take the ball and run back and forth for five minutes. The play would be terrific as he dodged, writhed and side stepped, the stands would be wild, the students throwing their hats. Finally, he'd be dropped—and it would develop that his net gain had been a loss of 17 yards!

Up forward, Lou Young, a dependable guard of last year was back. George Sommers, a substitute; tackle who came strongly at the end of the season was available. Spring practice had turned up one of those fiery midgets who come along occasionally—one of the Albie Booth, Warren King, Davie O'Brien type—whose name was Arico. Built like a rubber ball, he could bounce as hard and fast and was anything else but frail, but the sum total of his altitude was five feet five inches, and his gross poundage was a light 142. Such a young man is at a bad disadvantage on pass defense and you can figure what sort of blocks he can throw at a 200 pound six foot three incher comprising part of an enemy's secondary.

This was about all except some of the scrub material left around from last season, a back named Jack Orr, perhaps taking first rank amongst these.

There was enough to form one fair looking line and another to spell it, but the backfield figured to be the weakest and most impossible to mesh that has worn the Green for—well, my memory goes back now as far as 1915. I can't recall anything exactly like it. Maybe some of

you older gents can oblige. I visited for a spell with Coach Blaik last summer, and remember sitting out on flag stone terrace behind his pretty manse one starlit evening as he explained how he was even then revamping his system to try to find some way a back could run without a blocker to help him. He was still studying movies, changing this play and that, recasting assignments and wondering if this or that would help a little, if only a little.

But, to get on to what happened, apparently most of what happened was that those Dartmouth football players either didn't read the advance obituaries being so freely published, or if they did read them, they figured it slightly premature for the buzzards to start rattling their wattles while the corpse was still walking. It might be mentioned in passing that they likewise were catching plenty of coaching.

Especially was that true up front in that line. The battle is still won and lost in great measure up forward. We might have backs or we might not have backs, but a fighting strip of wildcats tearing at the other fellow's backs never exactly helped lose a decision. Dartmouth's Harry Ellinger is a great line coach. If that hadn't already been proved before, this season's team would have provided the clincher. The Messrs. Blaik and Gustafson kept experimenting with those backs. They must have changed them a grand total of 10,000 times. Hutchinson and Krieger, Orr, Hayden and Hall. Hutch and Krieger were the problem. Whether to play them at full back, halfback, have them spell each other

The first two games, the soft ones, went off all right, although the Green actually had trouble with Hampden-Sydney, aproud little place from Virginia with less than 400 students, Dartmouth had them only 7-6 at the half and might have had a tough time beating them if they hadn't worn them down with subs.

But the Navy game at Baltimore was the first real test, and a quick look at what happened made the Green look pretty lucky. The score was 0-0, Which means, of course, that Dartmouth wasn't able to generate anything approximating a scoring punch. They reached Navy's 13-yard line one time and the 19 yard stripe another, but there they broke apart. Most of the gaining was with passes anyhow. The Green lacked the power to grind it out the hard way.

But another sort of examination revealed a positive factor of no mean proportions, and that was a fighting Dartmouth defense that literally tore the bigger and more powerful Navy to pieces. This, as the season has proved, is a bad Navy team, "bad" meaning unsuccessful in the matters of wins and losses. But it wasn't proved bad at that time. It had formidable man-power and characteristic spirit. Too, it had its entire student body in the stands rooting for it. Dartmouth used 21 players, which was about all she had. Dartmouth couldn't score, but Navy couldn't get closer to the Dartmouth goal than Dartmouth's 33-yard line!

The old Ellinger poison was working up front. Maybe this Dartmouth team wasn't pretty but it proved it could and would fight!

Hutchinson played a great game, his kicking being especially beautiful and especially valuable. Capt. Miller played a magnificent defensive game at end. Little Sir Arico, the nickname being practically inevitable, likewise performed spectacularly. He darted through, past and around those hulking Future Admirals like a waltzing mouse.

Privately, the coaches were relieved to settle for a tie. They agreed as much walking from the stadium after exchanging the customary amenities with the Navy officials. When they reached the locker room, however, they found Dartmouth players crying.

"We should have won it for you, Mr. Blaik," one of the big linemen said, the mark of tears plainly on his dirt smeared face.

"That's right, sir," came from several others, in a sort of solemn Amen.

The coaches looked around. In the clatter and the bang and the general confusion of getting bathed, dressed and packed, they saw tears on more than one face.

The four coaches exchanged quick, significant glances.

They'd just learned something.

Whatever else they had, they had a fighting football team. Maybe it wouldn't be the greatest that ever wore the Green, but it would give all it had, and that's the full Dartmouth contract. No Dartmouth man the world over ever asks any more and outsiders haven't the right to expect more.

But they still hadn't a backfield.

Krieger had been the principal disappointment. He played a hard game and seemed to try with everything he possessed, but time and again when it seemed the stage was set for him to shake loose, he failed to gain a yard. Plain lack of backfielding savvy seemed to be his difficulty. On sweeps when he carried, for instance, the Navy end would drift with the play, fighting interferers outside with his hands.

When this happens, a smart ball lugger will cut swiftly inside, where he's almost always good for a gain and may go the whole way, but Krieger kept swinging deeper to the flank and trying to pass the drifting clot on the outside. Invariably he was run over the sideline.

The coaches, sure he was a good football player, and belonged in the team picture somewhere, decided to make what amounted to a revolutionary experiment. They decided to try him at end. Whether they knew it all along or just found it out in some fashion, Krieger was a star end in high school for two seasons before they switched him to half back.

The change was a positive inspiration! Playing one of the greatest flank games ever seen on Hanover Plain, the converted halfback tossed Lafayette backs all over the sod the next Saturday, was down the field like a greyhound under Bill Hutchinson's booming punts, and wound up in a fiery blaze by scoring Dartmouth's second and final touchdown on an end-around play stemming from a fake reverse that had not only Lafayette but the entire student audience completely bamboozled!

And young Mr. Krieger went right on from there in All America tempo, but I don't want to get ahead of my story.

The Harvard game rolled up apace and Dartmouth still didn't have a backfield. In fact, with Krieger at end, they had less backfield than before. It's no exaggeration to say that Dartmouth, going into the Harvard game, had the most pitiful looking ball moving squad, at least of modern times. There'd been various switchings and changings, but it was finally decided to play Hutchinson at one halfback, Hayden at the other, young Hall at fullback, with Norton and Courter relieving each other in the blocking job.

Jack Orr, the other "regular," was out with a bad shoulder hurt in the Lafayette game. There were only two substitutes. Subbing for both halfbacks was the 142 pound Little Sir Arico, who hails from

Belmont, Mass., and the substitute at fullback was a lad named Jim Bauman, who hurt his leg so seriously his freshman year that the muscles started to atrophy, and although Rollie Bevan, the trainer, took up with him where the doctors gave up,

and reported some progress through a year's constant massaging, part of which

was done at Bevan's home in the summer, he was generally considered unfit for heavy duty, although he might step in and flip a forward pass.

PATHETIC" BACKFIELD

That was the picture, four backs, two subs—one practically a midget, the other practically a cripple. None of the number was six feet tall. The heaviest of the lot weighed 175 pounds.

Harvard had a burly young team composed principally of sophomores, but good sophomores, big, rugged, fast and plenty of 'em. Harvard, incidentally, very well may dominate the Ivy League for the next two years. These youngsters may give the Crimson her best team since Haughton's hey-dey (before they are graduated). They should be hot as a firecracker in 1941. They were two years away from 1941 this semester, but still something of an unawakened giant.

This undermanned Dartmouth team gave them the most complete licking they'll probably ever receive, and the one they'll remember with the most chagrin for the rest of their lives. Lack of space forbids going into detail about it here. Briefly, however, part of the reason can be sketched. Mostly it was a triumph of shrewd defensive Dartmouth coaching. The rest belongs to the undownable competitive spirit of the Dartmouth players, principally, as individuals.

The Dartmouth coaches, keenly analyzing the Harvard offense, decided to gamble on Harvard passes and concentrate everything upon stopping Harvard running plays. To this end, they taught the Green forwards to use a seven man line with the tackle and end playing outside the Harvard wingbacks. This completely discombobolated the Crimson operatives, who couldn't find Green defenders where Coach Harlow had said Green defenders would be. This threw their carefully rehearsed assignments out of kilter and braked them down to a complete stop.

And one means complete stop. In 60 minutes of playing time, Harvard made exactly no first downs, gained a net total of thirty-two (32) yards rushing the football, and completed one forward pass for a total of five (5) yards.

No Harvard team within memory was ever stopped so cold, nor so completely bottled up. Picture a major team making no first downs and a grand total of thirty-seven yards with both rushes and passes in a mid-season engagement!

Only one word describes the Dartmouth defense and that's "terrific." Seldom has harder tackling, harder charging and fightinger football ever been played on any field than the Dartmouth's exploded into the face of the astounded and unprepared Cantabridgians.

For a half, the Dartmouth offense, as offense, didn't look much better. The Green got a touchdown on what was really a fluke although there was nothing flukey about Bill Hutchinson's weaving 37 yard sprint that wrote it into the records. But the play was strictly an accident starting out. Hutch was back to punt, and there was no mistake about it. The count was fourth down—nine on Harvard's 37 yard line, and the Dartmouth star was about to try for coffin corner. The center's pass was bad, however, and Hutch had to pick the ball off the ground, too far to his left to straighten up and give it any sort of a kick. So he desperately decided to run with it as far as he could.

He ran all the way to a standup touchdown. It was a great piece of extemporaneous broken field work.

And Sandy Courter, a spanking breeze behind him, split the bars with a 26 yard placekick further along, Dartmouth having been presented with a scoring chance but lacking power to proceed.

But the significant thing came along a little later. In an effort to give Hall some rest, the coaches decided to take a chance on Bauman, the young fellow whose leg injury had presumably ended his real football career. Bauman promptly began to roar through that Harvard line like Green fullbacks of yore. With this, he faded back occasionally, and with all the poise of any battle hardened veteran of the past, he tossed forward passes swiftly, sweetly and unerringly.

Suddenly the Green was marching, Bauman and Hutch smashing that heavy Harvard line or turning its flanks in steady advance and into this those sharp Bauman forwards kept moving the Green goalward. One of these expeditions drove steadily on for 40 yards and with the ball in pay dirt, Bauman faked a swing to his right, stopped, turned slightly toward his left and lofted a softly settling touchdown forward to Bob Krieger in the Harvard end zone. It settled into the tall new end's arms as gently and as securely as if somebody'd handed him a baby to hold. There wasn't a Harvard player within 15 yards of Krieger. It was a complete piece of fooling and a really perfect play. The score was 16-0.

The Dartmouth line played magnificently. Hutch had been wonderful, Krieger outstanding, and a new end, Jack Kelley, in for the injured Capt. Miller (that leg) also played great ball. Dr. Eddie O'Brien's son Bob, who didn't even go out for football last year, played a fine game at left tackle. The veteran Lou Young was a power. Sommers was a standout at tackle. Guenther and Dacey, sharing the job at right guard, played fine headsup ball. Stub Pearson, the sophomore centre, played plenty of pivot despite that one bad pass. Who'd dare call it bad, anyhow? It gave Hutch a chance to run for a touchdown, didn't it?

But the big news was in that backfield. The game had uncovered a new dependable, just maybe a new star. It was Bauman, the kid with the bad leg, which wasn't so bad anymore, thanks to the untiring efforts of the football team's trainer. But for Bevan, he might have limped to the end of his days. Now he was back starring at football.

And there was a new sort of respect around for that Mr. Cowboy Hayden, the unpredictable JayVee, who used to run mostly to the rear. It was suddenly recalled that he'd played 60 minute ball. He hadn't been nailed for any losses. He was out there on forward passes. He had tackled like 40 tons of dynamite. Mr. Hayden had also just come to the party.

I'm not going to linger over the Yale game that followed. It's too beautiful a story to be treated of briefly, and if I get to describing it in detail, I'll run the rest of the book. There's no point in going all the way overboard. Yale was just a week away from a trip to Michigan and a rolling in the dirt by what was at that time considered the crack team of the nation. Yale had a couple of key men hurt and this is generally considered something of a down Yale year any how.

THE SPECTACLE OF YALE

Still Yale is Yale, with plenty of football players and plenty of fight, down, or not, only Pennsylvania had beaten them in the east and by only six points. They'd whipped Columbia and Army. They had failed at Michigan, but, at least, they'd scored at Michigan, and that particular Michigan was called by every critic one with Yosts immortal point-a-minute nonpareils.

And this Dartmouth crowd obliterated Yale 33-0, which is the most complete thrashing Dartmouth ever handed Yale, and which comes within three thin points of being the worst beating Yale ever took in the Bowl from anybody—tops being the 36-0 walloping doled out by Percy Haughton's greatest Harvard unit away back there before the other war.

Mauman hammered the Yale line all over the lot, climaxing his assault with a touchdown. Krieger scored twice on smartly flung forward passes. Hutch hung up another with a 67 yard runback. Little Sir Arico skittered across for the other one. The Dartmouth line murdered Yale's running plays. They gained but 70 yards. Yale flung 34 passes, Dartmouth intercepting nine of them.

If there'd been any doubts about Mr. Cowboy Hayden after Harvard, there were none at all now. The young man was a really fine football player on that field.

An interesting thing about the Yale game was that the Dartmouth coaches fearing a close game and still worried about their offense, had worked out an entirely new type of formation. It was a pretty desperate looking arrangement, consisting of placing two backs side by side a yard behind the scrimmage line and well outside the end and pitching forward passes at 'em at every opportunity.

As Coach Blaik said, quoting some wag of the past, "It's a certain touchdown every time we try it—for one team or the other."

But Dartmouth never used it. They never had to. The orthodox maneuvres were bringing home touchdowns.

It was after that Yale game that the critics almost had to drown themselves in a body, and with simple honors, very simple indeed.

At rock bottom, however, they'd been correct.

Dartmouth had gone further than could be reasonably expected with nothing but nerve and courage and super-fine coaching. In sport, you can't continually make a liar of the form chart. There's just one thing stronger than a tough little fighter. That's a tough big fighter.

And yet such was the fight, the determination and the refusal to accept defeat that Dartmouth almost reversed the dope against a much more powerful Princeton Tiger. And Princeton was powerful. Although veteran and super horse-powered Cornell skinned the Bengal three touchdowns to one in the second game of the season, nobody else succeeded in doing the trick. Princeton had a veteran backfield featuring Dick Wells, whose father captained a Dartmouth hockey team just before the war, the famed Sheep Jackson, a great forward passer in Dave Allerdice and a new sophomore whizz named Peters, a more or less unexplained refugee from Tennessee.

They likewise had a big and powerful line that outweighed the Dartmouth forwards 10 pounds to the man, with a great tackle named Tierney and a squad of ends all well over six feet tall, especially trained to catch high, looping passes.

DAVID vs. GOLIATH

Dartmouth was outsized, outmanned, outweighed and out heigh ted. Yet so fierce was the battle and so spirited the Dartmouth play that the Green lost only 7-9 and might almost as easily have won 7-3.

Princeton got its touchdown by blocking a Dartmouth punt and recovering the ball on Dartmouth's nine-yard line. Dartmouth held the Tiger for downs on the one yard line, stopping Peters cold on the last play and under ordinary conditions would have been awarded the football and presumably would have kicked it out of danger. But an off side penalty against the Green was called on the play. Princeton was given another chance and Wells smacked it over.

The Dartmouth touchdown came in the fourth period when Bauman fired a gigantic forward pass to Hutchinson and then drove the ball over from the five yard line with a terrific smash inside Princeton's left tackle.

The score still would have been 7-6 in favor of the Green, but Princeton had a field goal punched out in the third period.

The Tigers deserved the ball game but it was a striking exemplification of how sheer fight can sometimes reduce the statistics to nothing. The Dartmouth fight took the form of over-eagerness too often, an over-eagerness that was translated into penalties and fumbles, but nobody can say the young men weren't trying. If anything they were trying too hard.

But to those who know the story, their whipping Harvard and Yale and coming this close to downing Princeton really rate them a great Dartmouth team, great in heart, in spirit, in loyalty and even great in execution, all things considered. And great, unusually so, in the coaching they received.

This is written ahead of the last two games of their schedule. These two are Cornell and Stanford. Undefeated Cornell is the most powerful team in the East, and holding a beautifully won 23-14 decision over Ohio State, it figures likewise to be one of the real powers of the nation. Comparative scores are notorious liars, but Ohio State has defeated this Missouri they're talking so much about, Northwestern, mighty Minnesota, Indiana and shhh! Chicago. Comparative scores, therefore, say Cornell is anywhere from two to 10 touchdowns better than all those.

On paper she figures to tear this little Dartmouth team to thin strips. You'll be reading this after whatever happens, but what do you want to bet this Dartmouth doesn't give them plenty of argument?

Those of us who saw Stanford on the Coast last year can't understand her season at all. That was a powerful Stanford team by the time it played Dartmouth. It had been injured all year but it was all right by the time we got there. Practically all of it was back for this season plus the first undefeated freshman team Stanford had had since 1921. Yet Stanford has lost every game except one, two touchdown tie with U.C.L.A. Even Santa Clara battered them 27-7, and while Santa Clara is no setup, especially this season, she's scarcely a Stanford in size or material.

So there's no guessing what that final game in New York will be, except, perhaps, that it will be played in comparative secrecy, two beaten teams having to buck the Fordham-N.Y.U. game for business but just wait until Boston gets her new municipal stadium!

Financially, Dartmouth drew well this year. Although it was announced, for some reason that the Navy Game crowd was 30,000, the actual pay-off was upon 49,000 bought tickets. The Harvard crowd was a disappointment, being around 30,000, but there were 58,000 at Yale and around 40,000 at Princeton. The Cornell game is a sell out on the small Hanover field. The Stanford game is a financial question mark.

My current job is officially finished in paying full tribute to a fine Dartmouth eleven who made up in heart what they lacked in numbers and size, and to a great job of coaching that has practically stopped every offense met to date by shrewdly changing the spacing of linemen so as to tangle the opposition's best Sunday plays.

Too BIG A JOB

If allowed the floor further, I'd say it's humanly impossible for teams as weakly manned as this one, especially in the matter of back field reserves, to play schedules of the type of this one—not only physically impossible, but criminally dangerous. Sixty minute ball on straight Saturdays against major opposition is no trick for 165 and 170 pound kids. Football is too fast these days; it hits too hard. We don't want any ex-Dartmouth halfbacks walking on their heels.

In discussing whether this is to be a permanent condition, we may be stepping pretty close to mined ground. Two woefully weak freshman teams dovetailed with mass graduation brought up the present situation. As to why the freshman teams were weak is where we veer close to the argument.

The theory commonly advanced around metropolitan sports writing circles is that Dartmouth has been determinedly turning away athletes, even legitimate and worthy ones, lest she be accused in some circles of "going out and getting 'em," and that the present situation is more or less the result. I can name at least a dozen strapping young men now making name and fame on other gridirons who "wanted to go to Dartmouth" and most of whom applied.

They were told either that they weren't wanted, or that they didn't have what it takes, but at least they seem to have what it takes to get along where they are. For whatever my vote is worth, I'm against hiring athletes, against lowering the entrance requirements or the eligibility standards, but I'm even more against being scared out of sensible policies by what anybody "thinks."

PLAYERS' PUNISHMENT

I'm against seeing a kid like Bill Hutchinson reeling around the middle of a ball field practically punch drunk from the punishment that's being poured into him because he's the star of the ball club and there's nobody to relieve him.

Speaking as one alumnus, maybe vox clamantis in deserto, I hope our athletic and administrative authorities will formulate a program covering the general subject of the admission of athletes—rather the admission of the worthy poor, who chance to be athletes, and somehow the conditions are almost invariably synonymous—will enunciate it openly and pay no attention to the hyprocritical quacking that may come out of some of the synthetic ivory towers overlooking the yard.

No public spirited institution in this America has the right to refuse the poor boy a chance to earn with his sweat what the rich kid can buy with his daddy's dollars, and if the poor kid chances to be a potential All America halfback, it shouldn't be held against him.

Happily, the 1939 freshmen have made an impressive record, although what will be left of them when the professors get through, remains to be seen. The academic executioners performed a rather amazing job last June when they flunked the best player on last year's freshman team out by some such margin as a tenth of a point in some such vital subject as classical French poetry.

But here's to the big little unit of 1939. Figuring where they came from, what they had, and what they did with it, just maybe they're as great a team as Dartmouth ever had. Just maybe there isn't a bigger word than courage unless it's loyalty, and when you get both, you may have the superlative.

That was Capt. Whit Miller's fighting, crying eleven.

They belong in the records. Wah-Hoo-Wah!

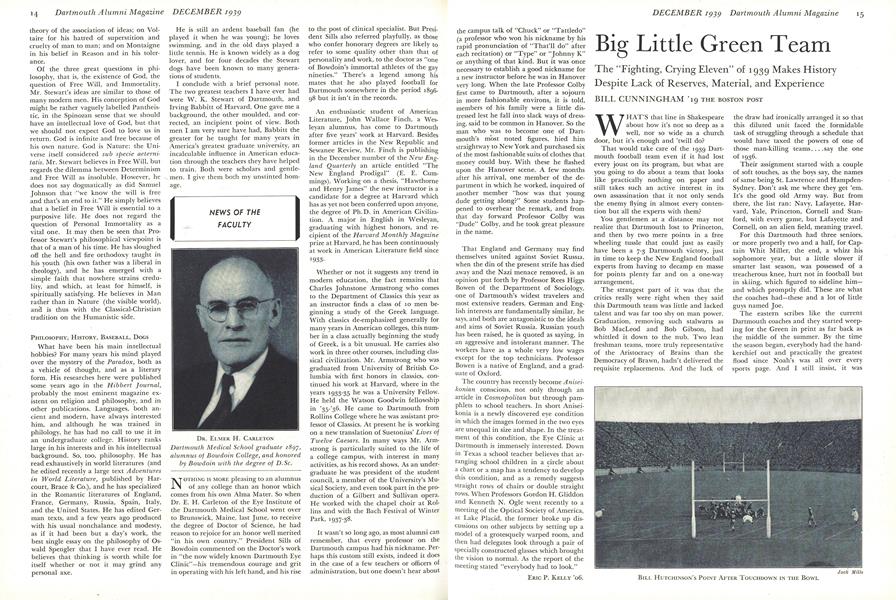

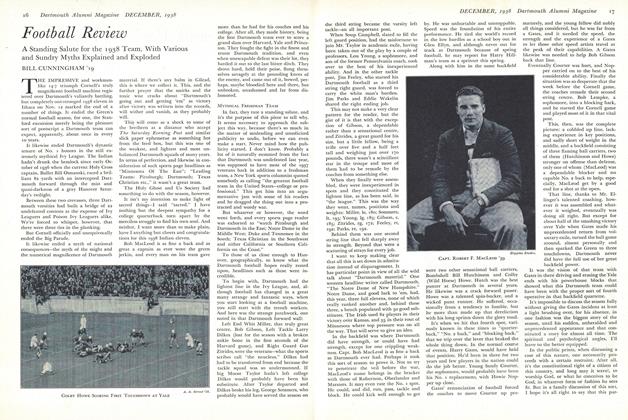

BILL HUTCHINSON'S POINT AFTER TOUCHDOWN IN THE BOWL

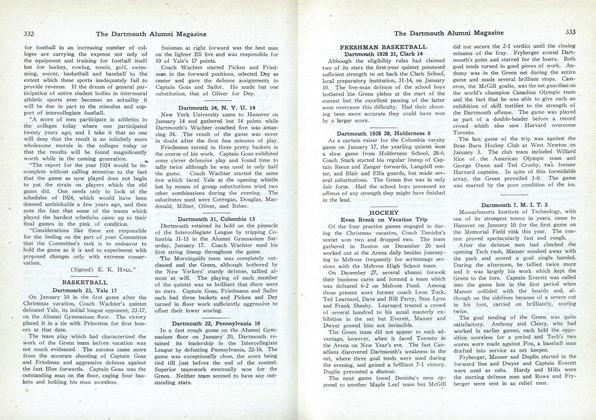

COACH BLAIK IN A THOUGHTFUL MOOD AND HIS SQUAD EQUALLY INTERESTED AT THE YALE GAME.

THE BOSTON POST

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleHe Makes Students Think

December 1939 By HERBERT F. WEST '22, ERIC P. KELLY '06 -

Article

ArticleA Landmark Is Gone

December 1939 By WILLIAM A. ROBINSON, Robert Lincoln O'brien '91 -

Article

ArticleGRADUS AD PARNASSUM

December 1939 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1931*

December 1939 By CHARLES S. MCALLISTER, CRAIG THORNE JR. -

Sports

SportsBig Green Teams

December 1939 By Whitey Fuller '37 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1929*

December 1939 By F. WILLIAM ANDRES, WILLIAM O. KEYES

BILL CUNNINGHAM '19

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLETTERS TO THE EDITOR

June 1935 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters

January 1941 -

Sports

SportsREBIRTH OF SPIRIT

December 1937 By Bill Cunningham '19 -

Sports

SportsFootball Review

December 1938 By BILL CUNNINGHAM '19 -

Article

ArticleDistinctive Student Achievement

November 1941 By BILL CUNNINGHAM '19 -

Article

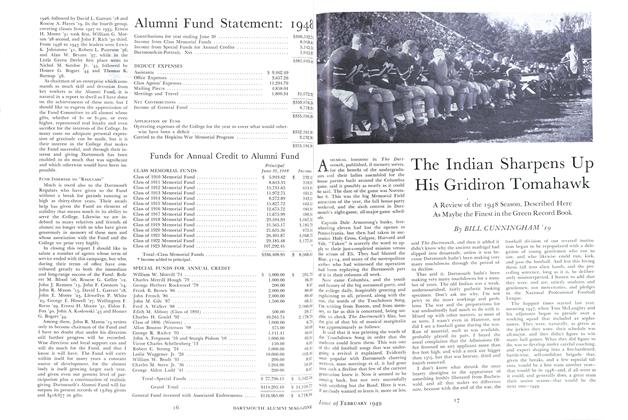

ArticleThe Indian Sharpens Up His Gridiron Tomahawk

February 1949 By BILL CUNNINGHAM '19