In the Days When General Sherman Said "War Is Hell But Dartmouth Commencements Are Worse"

IF THERE IS ever a proper time for man to sigh for the good old days it is at the thought of the old fashioned Commencement. The abbreviated form now celebrated is but a faint reminder of the grand histrionic display and boisterous carnival which grandpa knew.

Take the first Commencement for example. It had to be held under the wide and open sky, for want of a suitable building, but it was enlivened by the presence of the Governor, an imposing retinue, and his gift of a barrel of rum and an ox to be roasted on the campus. The Commencement of 1774 was a bedevilled celebration if there ever was one. Madam Wheelock was sick. The cooks got drunk. The harrassed Wheelock family overlooked a few dignitaries in the crush and they, offended, went home to make fun of the oratoryand the table linen. Yet the exercises occupied both morning and afternoon and Mr. Jeremy Belknap, the New Hampshire historian, has left an account of the dignity and punctilio with which the degrees were conferred. "Admitto vos," said the President to the candidates, "ad primum gradum in artibus pro more Academiarum in Anglia, vobisque tradeo hunc librum, una cum potestate publice prelegendi übicunque ad hoc munus avocati fueritis cujus rei haec diploma membrana scripta est testimonium." "Mr. Woodward stood by the President, and held the book and parchments, delivering and exchanging them as need required."

The nineteenth century was the golden age of Commencement. Whole chapters have been written on that of 1801 because Webster sulked and would not speak, since he had not been offered the Valedictory. Rufus Choate's biographer has lavished much space upon the Commencement of 1819 when Choate, haggard and dis- hevelled, staggered to the stage to deliver the valedictory, commending his classmates to the world, so generously, and describing his approaching death, so beautifully, (and some forty years early), that a local miss is supposed to have wept inconsolably into her washtub, the next day, at the mere recollection.

A typical Commencement began with the Baccalaureate sermon; or, as the Dartmouth Phoenix put it: "Early in the week before the 26th, divers evolutions of the knights of the scythe, pitchfork and paint brush, were omens, not to be misinterpreted, of some great events near by. These were ushered in in due time by the Baccalaureate on Sabbath afternoon

Monday's sun rose in thick clouds which soon relieved themselves of their burden of rain. But, notwithstanding Jupiter's position, the delegates of the two Literary Societies were seen, before daylight, en route for the woods in search of flowers and oak leaves to decorate the Libraries

On Tuesday .... the church was filled at an early hour in the evening to listen to an address before the Theological Society."

Wednesday was devoted to addresses by distinguished visitors before the Literary Societies and the Phi Beta Kappa Society, which had, also, an original poem written for the occasion and delivered by the poet. In the evening, there was usually a concert by a well-known brass band; but sometimes, another oration, or an oratorio by the Handel Society, and a display of fireworks. One impressionable youth remembered, long afterward, a serenade under the great elms of Hanover and Wendell Phillips responding: "Young gentlemen, this scene, this moonlight, this music, these students recall to me Germany and its student life, and as I think of Germany, I recall the words of that German poet, John Paul Frederick Richter, who said 'Very beautiful is the eagle as upon tireless wing he cleaves the upper Empyrean, and gazes with undimmed eye upon the noonday sun. But still more beautiful is the same eagle as in his might he swoops down upon his quarry that he may feed his young.' So, young gentlemen, it is well for you to soar in the realm of speculation and fix your eyes upon pure truth: but it is nobler that you bring your scholarship down to life and with it aid the needy."

The graduation exercises began on Thursday morning, at times as early as eight o'clock, with the procession, from the old chapel in Dartmouth Hall to the College Church, led by the band and the marshal, usually an officer in the bloodless militia, noted for his pontifical appearance. At least, that was the plan but one newspaper reported: "At the appointed hour there was a great rush to the chapel which was guarded by two men with rusty swords." In President Lord's administration, there were from twenty to thirty speakers, selected by what Ralph Waldo Emerson called "the old granny system." Dr. Lord did not believe in competition or rewards for distinction, and to avoid either, the speakers were chosen by lot. Even after his resignation in 1863 and the return of the merit system, the number did not decline greatly. A salutatorian of the eighties remembers that he was able to slip out the back door of the church, go down to Girl Brook and make a tour of inspection of the new cooperative creamery and yet be back in time to receive his degree from the President. There were Latin orations and a Greek oration but most of the graduates restricted themselves to the English language, on such resounding subjects as: "The relations of the Ideal and Actual"; "The extravagances of the present age on moral subjects no certain indication of deterioration of principle"; "The comparative success of Ancient and Modern deliberative eloquence"; "The Egyptian Obelisk in the Court of St. Peter's." They furnished a kind of "continuous performance" occupying most of the morning and afternoon. Members of the audience dropped out for lunch or came in for certain speeches with no formality whatever.

When the last flood of oratory was over, the officers, graduates and guests attended a dinner given by the College at the Dartmouth Hotel. One visitor, in 1853, complained that he was served only food.

"The dinner came off as only a Commencement Dinner comes off at Dartmouth. The mere animal was well enough cared for, but the intellectual lacked for food. We protest against such dinners,on such occasions. We can get a good dinner every day; but a Commencement dinner comes only once a year; and then we ould see the extra 'fixins'; and intellectual repast. 'A feast of reason and a flow of soul.' And this repast can be furnished without trouble. Only a slight alteration in the 'bill of fare,' and the thing is done. Instead of singing 'Old Hundred,' or 'St. Martyn's,' let the President but call out some of the numerous guests ever present upon such an occasion, and there would be no lack of intellectual entertainment." It is well to remember that that was the year when, beside the usual orations before the societies and the twenty-three student speeches, Rufus Choate gave a three-hour eulogy on Daniel Webster.

The final event of the year was a senior ball or the President's levee; sometimes both, one for the sacred and the other for the profane.

These were all the items on the program but they represented only half of Commencement. The nineteenth century version was like an Elizabethan play. If it furnished subtle delights for the learned, it also took good care of the groundlings. By Tuesday night, the College Green was lined with the booths and tents of peddlers, showmen, auctioneers and swindlers. By Wednesday noon, the whole countryside was there to enjoy them. The campus had more the appearance of a county fair than an academic institution. William Dewey, the Hanover antiquarian whose rigid conscience won him the students' title of "Corset Bill," noted in his diary: "July 31st, 1845. The annual Commencement this day & a very fine fair day too—The smallest literary procession that I have noticed for several years—but an unusual rush of all kinds of people from the circumstance that there was uncommon attractions for them. A somewhat extensive Menagiere of wild animals (in the most miserable plight however)— The Boston Brass band of Musicians—& the famous foriegn Violin player named Ole Bull—& 4 Albinos or white negros—Everything to pick away money & lead the minds of people from the great concerns of eternity & their duties of charity to their needy fellow citizens & the perishing heathen—Even clergymen were so enraptured with the mere report of the fame of Ole Bull that they could not resist the inclination to hand out their half dollar to hear him scrape his catgut—Bc another qarter to hear the brass band perform—Perhaps if they had been with our foreign Missionaries on perishing heathen ground all this music might not have [made] so lovely sounds in their ears as to induce them to bestow their money in just such a way as they have now done—Possibly they might have seen that it was more needed elsewhere."

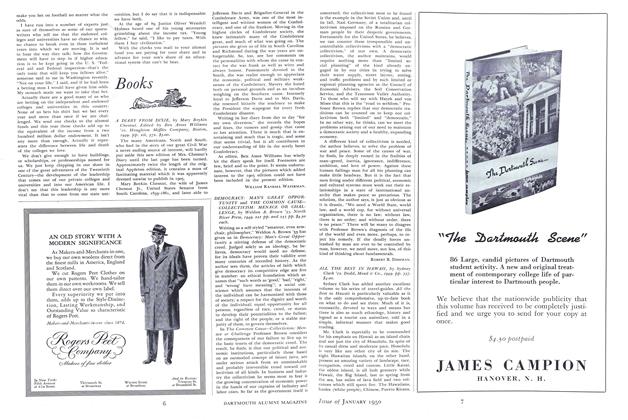

The Commencement of 1869, the centennial year, was a Commencement to end Commencements; and did, indeed, mark a peak never surpassed. It boasted twelve speeches and a poem by officers of the College and visitors; twenty-one orations by students, exclusive of the prize-speaking programs and class day exercises; two concerts; a gymnastic exhibition; an alumni meeting; the alumni dinner; and the president's levee. Francis E. Clark '73, has described one distinctive feature of it. .

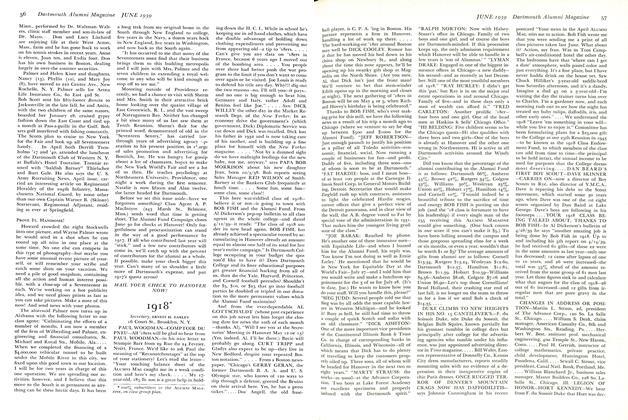

the Chief Justice of the United States, Salmon P. Chase, presided at the Alumni Dinner in a great tent pitched on the campus, which was also graced by the presence of General William Tecumseh Sherman, then comparatively fresh from the glories of the battle field, and acclaimed as the second greatest general of the Union Army. Of course Daniel Webster and Rufus Choate were eulogized, as they have been at scores of Commencements since their graduation. But on this occasion the glorious things which were spoken of Dartmouth and her distinguished graduates were cut short by a tremendous shower of rain, which caused the Chief Justice of the United States, the Lieutenant-general of her army, and as many others as could possibly do so, to take refuge under the speakers' platform from the deluge that poured through the dry canvas. Alas, their last estate was worse than the first, for there were wide cracks in the platform, through which the rain poured down upon their devoted heads, not in drops but in rivulets. If I remember rightly the shower soon abated and the exercises proceeded to the end without curtailment, in spite of the damp and dripping condition of some of the principal speakers. Owing to the somewhat meagre preparations for a crowd, which was much larger than had been expected, and with reference to the principal articles on the menu of the alumni dinner, the punster declared that it was 'merely a salmon, pea chase.' "

Perhaps this explains the persistent rumor, never proved, that General Sherman said: "War is hell but Dartmouth Commencements are worse."

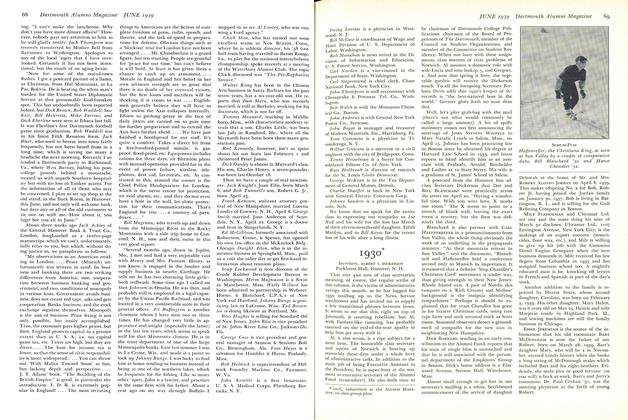

DARTMOUTH'S COMMENCEMENT DAY ON JULY 22, 1869 As drawn by an artist of Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper, and published in his issueof August 14,1869, the sketch shows the interior of the great tent with General Shermandelivering an address during the Centennial Celebration of that year.

ARCHIVES DEPARTMENT, BAKER LIBRARY

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Sports

SportsBig Green Teams

June 1939 By Whitey Fuller '37 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918*

June 1939 By ERNEST H. EARLEY -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

June 1939 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1929*

June 1939 By F. WILLIAM ANDRES -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

June 1939 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1930*

June 1939 By ALBERT I. DICKERSON

MILDRED L. SAUNDERS

Article

-

Article

ArticleNEW CATALOGUE PUBLISHED AND NEW COURSES ANNOUNCED

February 1921 -

Article

ArticleNamed Headmaster

June 1934 -

Article

ArticleMasthead

DECEMBER 1966 -

Article

ArticleKeeping Busy and Keeping Up

September 1978 -

Article

ArticleNovels that Came in from the Cold

APRIL 1998 By Kathleen Burge '89 -

Article

ArticleTRAINING FOR AMERICAN CITIZENSHIP BY THE PUBLIC SCHOOLS OF PORTO RICO

JUNE 1906 By L. R. Sawyer '00