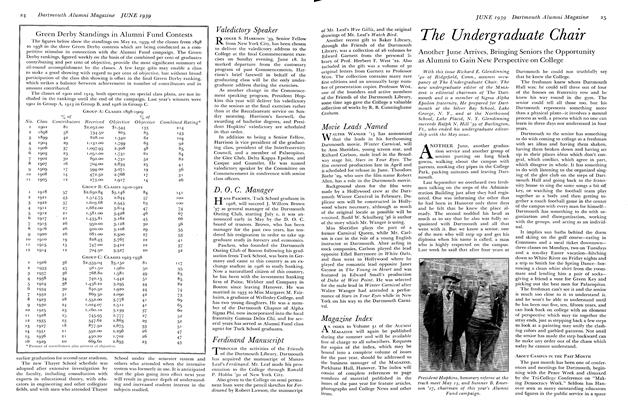

AS a Youth, Before Entering Dartmouth with the Class of '85, His "Poems" Was Privately Printed

THAT RICHARD HOVEY, toward the end of his sixteenth or the beginning o f his seventeenth year, printed a volume of poems has been known to biographers, critics, and bibliographers,1 but the work has apparently never been described for the very probable reason that no one has ever been able to examine it. The Stanford University Library has, however, recently acquired a copy of this rare little book, accompanied by the following letter,2 which will explain something of its origin:

Dear Percival:For your love of Hovey I have beggedthis copy of his mother. The poems werewritten by Richard between the ages ofii & 14—they were set in type, printed,and bound by himself and his boy friendN. B. Smith who had a small printingpress in Smith's fathers law office. To-gether they set the type, read the proof,cut the paper and bound the books—andthe family knew nothing of it until thebooks were completed. Not over 100copies were printed and Gen. Hovey tookRichards copies telling him he would besorry for the juvenile indiscretion. Nonehave ever been sold. In my copy, whichwas given me by Gen. Hovey in 1895,Richard wrote, in 1898 "Who can beashamed of having been a boy."

Laurens K. Maynard

September 1902To G. P. Wiksell

Whether the zeal of General Hovey in guarding the future literary reputation of his son resulted in the destruction of the whole impression (except for two or three copies preserved by the fondness of Richard's mother or presented by him to some of his intimates) is unknown. If Maynard is right in saying that Hovey wrote the poems between his eleventh and fourteenth years, there was then an interval of two years during which he composed nothing, or at least nothing which he cared to include in the volume. It seems more likely that some of the pieces were of later date than Maynard thought. The book is a thin pamphlet of fifty-nine pages, bound in blue-gray paper covers4 and with the following title and imprint: POEMS/ BY/ RICHARD HOVEY/ WASHINGTON/ N. B. SMITH, Printer, 615 7th Street, N.W./ 1880. The contents are divided into two parts, the first of fourteen, the second of three, pieces.

To my perceptions, at least, these first efforts offer no clue whatever to the later Hovey. The Arthurian legend, which was to engage him so closely in the Launcelot and Guenevere cycle of poetic dramas, had apparently not yet caught his fancy. Nor had he yet been touched by the gypsy mood of the Vagabondia songs. One instance of the word "valkyr" hardly proves that he already had the knowledge of Northern mythology which he was to make use of in The Quest of Merlin, where the old magician consults the inscrutable Norns. He was still to set up the opposition, false but perennially attractive to poets, between something called "life" on the one hand and thought on the other, as when (in The Quest of Merlin) he makes the Maenads sing,

Thought is gray and life is greenThese are what men choose between.5

He was still too young to take any interest in his contemporaries or in current questions, as he subsequently did in such pieces as "Verlaine,"8 "Henry George,'" and "Peace,"3 and in the strident, breastthumping, Anglo-Saxon righteousness of "The Battle of Manila," "The Word of the Lord from Havana," and the other Spanish-American war songs.9 There is not much to suggest that he had learned to observe, to think, or to feel for himself. Though he uses several verse patternsrhymed octosyllabic couplets, some unrhymed stanzas, six-, seven-, and eightline stanzas variously rhymed, spenserians, some lines in the manner of Evangeline, one piece in anapaests—there is little to forecast that metrical facility and ingenuity which distinguished his later work.

Poems are the exercises of an alert schoolboy who has been attentive to his books and who shows a certain readiness in picking up the more well-worn conventions of the poet's craft. Young Richard may well have thought to himself: "When a gentleman turns out a volume of verse, he should include in it some praise of love, some praise of nature, some praise of former poets, a bit of humor, and, finally, some evidence of his acquaintance with the Latin classics." Accordingly we find pieces titled "Lilian," "Love," "To Juliet," and "To Edna." The perfections of these ladies are described in terms of dimpled cheeks, sylph-like motions, skin as white as snow, eyes glancing like sunbeams, pearly teeth, coral lips, and dulcet voices. In the presence of Lilian, in the appropriate setting of a dewy dell, the young poet feels an unaccountable, but sweet, sadness steal over him. Edna, a sterner creature, whose "brow is as dark as a thundercloud," and "eye bright as the lightning,"

... is a soul that dwells apart, A wild, poetic spirit,

who glories in the tempest.

In "Song of the Wind," "The Hermit Thrush,"10 the three Odes ("To Laughter," "To Melancholy," "On Memory"), and in the pieces mentioned above are descriptions of woods and fields, skies and waters, in the diction made familiar by long use—babbling brooks, crystal streams, limpid springs, ambrosial waves, pallid moonbeams, rosy tints of morn, zephyrs, and the rest. He sees no incongruity in an American's using terms like "moor" and "peasant's cot," and he is sometimes insensitive to the connotations of words, as when he speaks of the thrush returning to its "morass," and of the tempest "tearing" by.

The boy poet makes his bow to the classics in two renderings from Horace, one of which he calls a translation, the other a paraphrase. The two selected are the ninth and twenty-second of Book I of the Odes. Hovey's versions are creditable, even when compared with those of more mature translators.

In paying his respects to the poetic great of former times, he chooses Shakespeare and Shelley for his subjects. It is the transcendental yearnings of the latter that stir him to admiration: sweet bard! who Dids't seek to know the why— In thee the love Of nature and her loveliness was mixed With the desire to know the things above Our comprehension fixed.

"Skakspere" is as well conceived as any piece in the collection and may be given in full without, it is hoped, doing injury to the fame of Hovey or giving too great offense to the watchful spirit of his father, the General.

Bright are the stars of the night; Fair is each twinkling ray; But at the earliest light Of morning they vanish away But with the son's dawning beam Like ghosts they vanish away.

Sweet-voiced are the bards of our tongue, And melody floats in each lay; But, gazing on poetry's sun, Their memory fadeth away-Their fame and their memory fadeth As the stars at the dawning of day."

The second part of the volume is reserved for the three humorous pieces; two are narratives, and the third is quaintly titled "To a Fragment of Rock, formerly the highest point on Mt. Washington, now a paper-weight in the author's possession."

"A Horrible Tale" is in the mock-heroic style, with its apostrophe to the heavenly muse, reference to Parnassus, Pegasus, etc. Amusing enough and handled not without skill, it has the look of being founded on an actual incident and of referring to an actual theatrical performance in Washington. The "herohypocrite" beguiles a party of ladies into accompanying him to witness a play disarmingly called "Babes in the Wood."

But the babies, acting in this play,—alas!—Were not as innocent as babes should be; Their drapery, too, was scanty for a lass, Disclosing rather higher than the knee.

The ladies, shocked, though they cannot forbear to look "'twixt their fingers," ostracize the unabashed jokester, but at length relent. It is apparent that the juvenile author has a boy's relish for toying with what he conceives to be slightly indelicate. The last poem of the volume, "Reflection," which uses comic rhymes, is more labored. Suggested by his classroom study of natural science, it relates the betrayal of a pair of kissing lovers by their reflection in a glass, and concludes with the caution to

. . . . remember, e'en though tasting love's confectionery, That the angle incidental equals that reflectionary.

Without insisting too much on the correctness of my impressions, I seem to hear in these juvenilia echoes of various poets, of Milton in the opening poems of the book, "Ode to Laughter" and its companion piece "Ode to Melancholy"; of Poe12 in the modified repetition at the end of a stanza, as in "Shakspere," quoted above. But certain features—the conventions of the diction, the apostrophizing, the personifications of melancholy and memory so dear to the hearts of the Augustans, the scraps of classical learning, the mold of the thought, the tone of the voice—all suggest inescapably the minor versifying of the 18th century. It is a curious testimony to the strength and persistence of literary tradition in the classroom that an American schoolboy of 1880 should have passed back over the two or three romantic generations preceding him to find his models in the pseudo-classic age.

Though Poems, the unacknowledged child of Hovey's youth, can hardly be the object of serious criticism, the interest of readers and students in the first flights of poets, however faltering, will not be suppressed. Hence no apologies are, perhaps, necessary for bringing this little book thus partially to light after the lapse of more than half a century. And, in the poet's own words, "Who can be ashamed of having been a boy?"

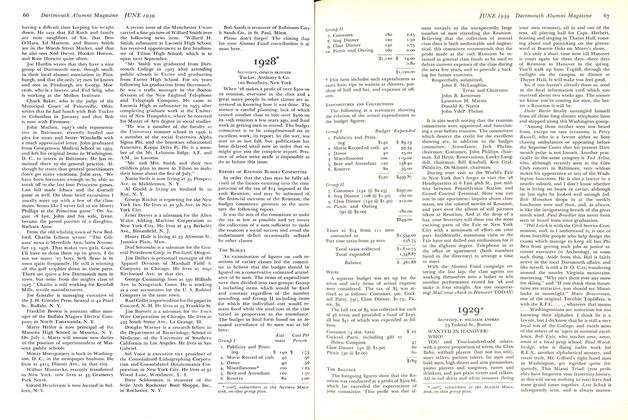

A STUDENT ROOM IN THE NINETIES The quarters of William F. Whitcomb '96 in No. 10, Thornton Hall.

DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH, STANFORD UNIVERSITY

11 find it mentioned in the following places: Jessie B. Rittenhouse, The Younger American Poets, Boston, Little, Brown, and Company, 1904, p. 349; Percy H. Boynton, American Poetry, New York, Charles Scribner's Sons, 1921 [l9lB], p. 688; TheCambridge History of American Literature, New York, G. P. Putnam's Sons, 1921, IV, 648; TheDictionary of American Biography, Vol. IX, New York, Charles Scribner's Sons, 1932 ; Merle Johnson, American First Editions, revised and enlarged ed., New York, R. R. Bowker Cos., 1932, p. 185. 2lt is through the kindness of Mr. Nathan van Patten, Director of Stanford University Libraries, that I have been able to examine these items. 3 Laurens Maynard was a member of the firm of Small, Maynard & Company, Hovey's principal publishers. 4 Merle Johnson, op. cit., describes the work as in "cloth or wrappers," whether on the authority of a copy which he had himself seen or merely by report cannot be ascertained. It is, however, very unlikely that the two boys bound any copies in cloth. 6 P. 29. 6 In More Songs from Vagabondia. 7 In Along the Trail.8 In Last Songs from Vagabondia. 9 In Along the Trail. Others of the same order are "Delsarte" (in Along the Trail), "New York," "To James Whitcomb Riley," and "To Rudyard Kipling" (in Last Songs from Vagabondia). 10 The hermit thrush served him later as a poetic symbol in his elegy, Seaward, on the death of the poet Thomas William Parsons, published in 1893. 11 Hovey returned to the theme of Shakespeare with the fine tribute "Shakespeare Himself: for the Unveiling of Mr. Partridge's Statue of the Poet" (More Songs from Vagabondia, 1896). 12 Helena Knorr says (Poet-Lore, XII, 437, JulySept., 1900), indeed, that Poe and Lanier "were his acknowledged masters." But whatever he may have acknowledged, Jessie B. Rittenhouse (TheYounger American Poets, pp. 1-3) finds him to be a poetic descendant of Whitman.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Sports

SportsBig Green Teams

June 1939 By Whitey Fuller '37 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918*

June 1939 By ERNEST H. EARLEY -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

June 1939 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1929*

June 1939 By F. WILLIAM ANDRES -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

June 1939 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1930*

June 1939 By ALBERT I. DICKERSON

Article

-

Article

ArticleSeniors Elect Officers

April, 1911 -

Article

ArticleProgram of the 28th Annual Winter Carnival

February 1938 -

Article

ArticleThayer Elects Overseer

June 1943 -

Article

ArticleSearch Is Under Way

July/August 2012 -

Article

ArticleTuck School

MAY 1972 By 808 KIMBALL T'48 -

Article

ArticleRECOLLECTIONS OF RUFUS CHOATE

April, 1922 By Miss M. A. CRUIKSHANK