A Dissertation on Leaves, Fences, Dartmouth Dualism and Many Other Things Making Up an Unusual Year

THE BRIGHTEST LEAVES fell first in midOctober, and suddenly the autumn became almost the winter. Things happen fast this year. It seemed that the yellows, reds, purples and many greens up the hill-slopes were more alive and brilliant than ever; and their quick decline into brown and into the ground seemed to take only overnight. With that the grey clouds of winter came, and the suns went down in narrow bands of red across the west, or in a sky so dark there was no sunset for us, only more darkness; or (on the clear days) in a sudden way that sent long shadows across the campus and laid a bronze cover on the leaf-covered grass in front of Dartmouth Hall.

Not for long, though. The busy men of the Department of Buildings and Grounds attack all fallen leaves with long-handled rakes and damned machines. That Department is anti-poetic, and I saw the editor out there one afternoon begging the foreman to call off his rakers until Bouchard could get a photograph. It's probably on the cover by now, but don't you believe it. Ten minutes after the picture was taken there wasn't a leaf on that lawn, and the wire fence was still around it to keep the boys from moving in the easy, natural lines of movement: which, for boys, are always across lawns, with fallen leaves to scuff through and the late-afternoon smoke of burning autumn to smell.

The above observation, couched in the mellow terms of a man with slippered feet resting on the hearth, is essentially serious. Take it as a figure for the conflict between freedom and authority; take it also as an example of how Dartmouth alumni like to think of Dartmouth versus Dartmouth as it is.

There stands the College of your dreams, gentlemen, with shadows from the empty elms stretching across the leaf-strewn lawn of Dartmouth Hall.

There stands the College, gentlemen, with four men picking up the leaves in a machine from a lawn which is fenced about with wire.

The two pictures represent the trouble with Corey Ford's imaginative, comical and charming "Can I Get In?" in the last issue of this MAGAZINE. He wrote that his only qualifications for being accepted as an alumnus of the College were his "genuine feeling for Dartmouth, a regard for what it stands for, a sincere desire to serve it in any way I can." The feeling, the regard, the desire to serve are based on "the most inspiring location of any college in the country .... the greatest college songs the outstanding college president of our generation .... its graduates "

Most alumni probably agreed with that It corresponds with the first picture per. fectly. But where does the second picture come in?

It's no good to laugh off the clean-up machine and the wire fence, because in a very real sense they represent the part of the College which is most often with us who are in the middle of it. When we leave to sit before the fire and dream, or when we know the College through "reunions .... in the fall .... in the winter Carnival .... in the spring, when the bare elms are first sifted with green," or even through browsing "in that magnificent library," or especially through the circus snap-the- whip of Commencement, we may overlook the second picture too. It will be too bad if we do.

Really, too bad. Because any picture that's only half a picture isn't much of a picture. And as regards this Dartmouth: we make a Hollywood picture of it, a picture out of Life, or a story from the SaturdayEvening Post. The Post's slogan, "America Between Two Covers," is not less true to life than a Dartmouth voice singing "the drifting, dreaming walls" and letting it go at that.

The walls of Dartmouth are hard red brick, and don't you forget it. There's nothing drifting or dreaming about Mass Row and the south end of McNutt and the corner of Parkhurst. I can see them from where I sit, and behind them are a lot of people very busy with recitations, listening to lectures, working over filing systems, writing a letter to the girl, worrying concretely and immediately about an hour exam, the present standing of Naval Reserve men, and the chances of the football team.

In the offices of the Personnel Bureau on the second floor of McNutt a boy is being told that he can't have any more financial assistance because the College has no more money. He is growing small inside himself with fear of having to leave, and the man across the desk wishes he ha a million dollars to give out in scholar ships. Upstairs they are correcting a Psj chology quiz: the students studied or didn't study, wrote well or poorly, and the in structors are bored, disgusted, occasionally pleased.

Beyond in the Administration Building one Dean is reproaching a freshman who is behind in his social science, and another Dean is bawling out a student who " seen drinking downtown Saturday night. And maybe both Deans would like to step around the desk and put an arm over the boy's shoulder and talk to him as a friend; but they can't do it any easier than either boy can explain why he didn't study or why he got drunk.

In another office an order is being given to rebuild a fence that was ripped up from in front of Robinson Hall. In another office are people adding and subtracting columns of figures, and one of them is thinking that if all these figures were laid end to end it still wouldn't make much difference. Down the hall they are rejoicing that at last a student has registered from Nevada; but a couple of them must think that it's not of titanic importance, it certainly doesn't make the walls drift or dream for them.

The President looks out his office-window from time to time and feels the deep satisfaction of the campus and the whitewashed brick buildings beyond the trees. But it would be very hard on the whitewash for next year if he overlooked the mass of administrative detail on his desk, or the difficult job of preparing speeches for the alumni banquets; hard on the College if he forgot the intense public and personal problems entangling the lives of all those boys behind him in Mass Row and the Gold Coast.

From one year to the next we remember the happy times, the time we went to Windsor to celebrate Hod's birthday, the party at the Nass that made us forget Princeton's victory, the Glee Club singing on the steps of Dartmouth, the afternoons up the Pompanoosuc with the beer in the sunshine naked on the rocks; but most of the times are not drifting and dreaming. The times we grow up are not so easy to spot, because growing up is a slow process. Only once in awhile does a growing pain make you wake in the night with a start. The every-day job of college, the battles that are tougher just because the battle lines are hard to define, the occasional realizations that the fellow on the other side of the desk gets bored and has moments of exhilaration too, don't stand up so straight in the memory. But they make the man.

That must be known by any instructor, any administrator, or any student who looks underneath himself for a minute. It must be known by any alumnus who looks back for a minute, beyond the shadowy elms and the voices softly flowing. Remember a voice that snapped at you once!

Or better still, remember a voice or two that over a year or four years made you 11 out what was in yourself. A man who could remember a voice that had made him whole, or a slow building process that Put him on a path he still could stay on: he might be called educated.

He certainly couldn't be called educated and the songs they sang about it. Or at least you couldn't say that he had a college education. And if the college were Dartmouth, you wouldn't want to admit that.

As for the conflict between freedom and authority, there is the strange case of the student separated for being discovered by a night watchman peacefully (if soddenly) sleeping in a dormitory not his own. Reports vary, as is their custom, on where he was found: some say in a freshman's bed, some say in the hall, some say he was only sentimentally trying to move back into his old room.

That's what happens to a man who mixes liquor and college-sentiment. He gets separated.

But the lad's Tuck I classmates and his fraternity brothers circulated a petition asking his reinstatement. It got 1617 signatures—half again as many as last spring's petition to keep America out of war. Dean Neidlinger, in one of the classic moves of American higher-educational strategy, issued a counter-petition stipulating that the boy would be reinstated if an equal number of students signified their understanding "that the College will not tolerate uncontrolled or uncontrollable drinking." This one only got 1314 signatures, but it bags, the M.I.T. undergraduate newspaper remarked that "it's lamentable that the College officials saw fit to adopt this nursemaid attitude," and the college settled down to the quietest houseparties since 1920.

The cause for the unaccustomed houseparty austerity goes deeper than the administration's Carrie Nationism, I think. I was dead wrong last month in guessing that the more stringent rules would make for "a driving-under-cover of the once open and carefree Dartmouth pleasures." Everything was under wraps, not just under cover. Fear of the administration had something to do with it; the general unrest over the war had a lot to do with itthere is no trying to escape the world seriousness as you might expect; and there is a definite truth that the drinking classes move in cycles just as the football teams move in cycles. A lot of it is described in a very thoughtful column from a recent Dartmouth, a "Minority Report" titled "Dartmouth, 1940" and signed "J.T."

"The College is busting up The College, as a one-time symbol of security and of 'a man's four happiest years,' is going This atmosphere consists of little things, of phrases you almost didn't notice at the time, of an administration which tries to forestall drinking which they fear will reach new heights in 1940, of a College Chest drive in which even the collectors fail to cooperate, and even of a football team which seems curiously devoid of drive

"The world is going through Big Stages and Big Things are happening—even to Dartmouth College, 100 miles from a major city, 280 miles from New York City, 530 feet above sea level, tucked away in the Indian country of old New Hampshire between a slowly flowing river and a gentle row of hills A big restlessness, a big uneasiness enfolds the College Three boys leave one day for Pensacola. No fuss, no pretensions

"The academic side of Dartmouth .... is beginning to mean less and less The professors are teaching the same important things, but the Big Things of 1940 history make the important things of the classroom and the library and the examination seem ridiculous

"And not even the Dartmouth myth, the Dartmouth spirit, the Dartmouth unity, or any part of the glory of being a Dartmouth man can hold up time nor stop the wind nor ease the mind."

Wow.

This column was unusual in that it caught the temper of a whole community; and especially unusual in that the community admitted the column was accurate. Nobody seemed to know the answer, but everyone admitted the uneasiness that shadowed the campus. Even an intelligent vox pop from George Herman '41 stating the need for the College to bridge the gap between past and future didn't make it easier for anyone to build a bridge. That seems to be the need this season: a practical engineer with a set of blueprints.

I'm glad to report that the quotient of realism has advanced so far that hardly anyone thinks such a man will be found, or that his blueprints would be more than academic, or that his bridge would be any fun even if it were practical.

The thin Saturdays of the football team may be called a result of the querulous times, or they may be called a cause. Probably it's a reverse-action proposition: like the dilemma about cheering, in which the team doesn't roll unless the stands are shouting and the stands don't shout unless the team rolls. Name your poison and you can take it away.

Serry the tailor has a theory, worked out over 35 years in Hanover, that when the team is down the whole student-body is down, interest in everything slackens, business drops (who wants to buy a new suit to wear on the losing side?) and the world is weary. Other merchants on Main Street are not so ready with explanation, but long faces grow daily longer as the customers continue to stay away. George Gitsis has been forced to close the Campus Cafe at 8:30 every night for the past few weeks, a savage blow to the small but loyal band who for years have made the Campus more a club than a restaurant. George, dean of Hanover restauranteurs, blames everything on the war, fretfulness about the draft and the election, no one sure of what will happen next, and the all-around nausea of our mal de siecle (George doesn't call it that but that's what he means). What really has ruined the Campus, of course, is a local phase of the mal de siecle: the escaoe into chromium and indirect lighting. Behind the Georgian fronts springing up on Main Street lie all the evils of Hollywood interior decorating and the Taylor industrial speed-up which gets the customers in, feeds 'em, and gets 'em out so somebody else can sit down. A college generation trained in Park Avenue movies and the one-arm lunch technique can never appreciate the old-world ease and mouldiness of an eating-place with a courtly tradition and a proprietor who is more than a strawboss.

To get back to where sentiment sidetracked us: the team has just run into a streak of bad material and has had some tough breaks. Everyone was very proud of it after the tremendous battle in the Princeton game, which would have been a fine victory if only someone had thought to break Allerdice's arm beforehand. The wry motto the week after that was "Lose to Cornell by a Low Score." But the philosophical say it's only a cycle, and nearly everyone resents the already-mounting murmurs against Mr. Blaik. The selective process being what it is, and the College maintaining its scholastic standard such as it is, the coach can't be blamed for a lack of Harmons.

There is the more serious charge that Dartmouth itself takes the punch out of men in the course of one year. Driving freshman football players come up to spring practice with a la-de-da, with a what-the-hell, with a football's-not-impor- tant air. That attitude is rooted in such easy cynicism as the College fosters; it seems to go with education that points out fallacies in popular thinking, but it goes even more with the fashionably blase air acquired by lots of college boys, the cultivated indifference of the man who thinks enthusiasm is equivalent to being wet. And being wet is the unforgivable college sin.

Don't ask me who is to blame for that.

[Editor's Note: Mr. Bolte came in to addthe following paragraph after the Cornellgame.]

Everything went crazy in the Cornell game and nothing anybody ever said before the game had any validity afterward. Mr. Blaik said in September: "On one occasion the team will rise to great play," and that was it. It was the most exciting football game anybody could remember, and Dartmouth played harder, better and more savage-joyously than any team I ever saw. The cheers were almost terrifying in their power, and on the fifth down Cornell touchdown the silence was as if everybody's heart stopped. Then there was a victory rally in front of the Inn, with the score still Cornell 7, Dartmouth 3. Even if Red Friesell didn't reverse his decision, even if Cornell didn't concede the game to us, we were celebrating a victory: the team over itself, the great new team that was made up of fighting spirit and Mr. Blaik's fluid defense. And by contagion it became a victory of the College over its disintegrating process, too. After Cornell no one could say the College was busting up.

Gag of the month: "I hear the Administration is planning to fingerprint the beerglasses in the Coffee Shop." Corollary: You have to show your draft registration card to get a glass of beer in White River.

The Dartmouth has been changing its mind about the war along with nearly everyone else, and has at last achieved a position of near-respectability in the official College by coming out flatly for aid to Britain and by supporting conscription. In a long editorial explaining how they came to change their minds, the editors said:

"We know now that the fascist war is to supplant democracy with the philosophy of force. The English are fighting for an even chance to work the way they want to, say what they think, have children when they feel like it, and relax after hours for talking and singing in anybody's beer parlor.

"Now we know we have to fight fascism too, not by declaring war on Germany, but by helping Britain with planes, guns, medical supplies, and all the boosts to morale that can grow from a quiet determination to make our own democracy so alive with chances that nobody will want to swap it for the fake efficiency of totalitarianism."

And if we do have to go to war: "We would fight as the men in Sherwood s 'There Shall Be No Night,' with grim resignation: the grim resignation that comes from the knowledge that at certain times only fighting will save what men have once won and now stand in danger of losing; the grim resignation to the truth that the winner takes nothing but has to win so that his opponent will not take from him what he has."

This statement of belief was popular with the Right People, and also with quite a few of the people who will have to the fighting if there is any fighting to be done. Although there is still plenty of opposition. The year continues to be in teresting and exciting.

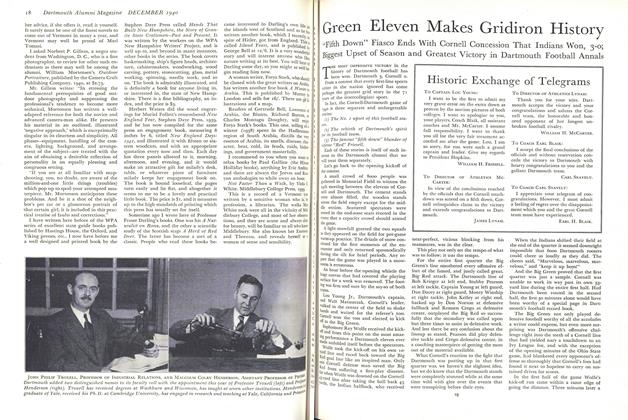

STUDENT GROUP PROMOTES INTER-AMERICAN RELATIONS Roberto Herrera '43 of Guatemala City explains a Guatemalan Indian dancing mask tomembers of Ambas Americas (Both Americas) inspecting the new Tozier Collection atthe Dartmouth College Museum. Left to right, Jorge R. Pradilla '44, Bogota, Colombia;Joseph E. Lopez-Silvero, Jr. '42, Havana, Cuba; Joaquin J. Vallarino '43, Panama, CanalZone; Herrera; Chester S. Williams '41, Needham, Mass.; and John H. Harriman '42,Buffalo, N. Y.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

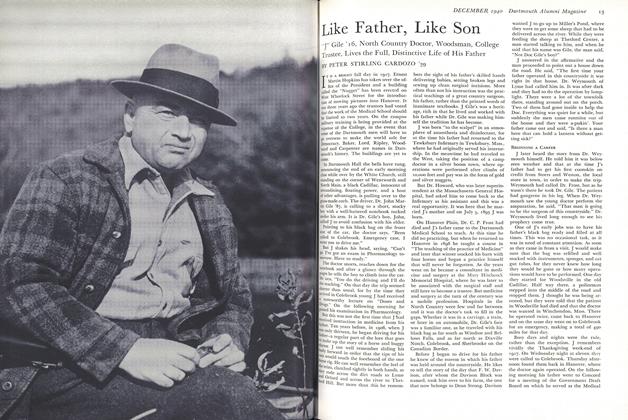

ArticleLike Father, Like Son

December 1940 By PETER STIRLING CARDOZO '39 -

Article

ArticleAmerican Student Morale

December 1940 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1917*

December 1940 By EUGENE D. TOWLER, DONALD BROOKS -

Article

ArticleGreen Eleven Makes Gridiron History

December 1940 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1935*

December 1940 By JOHN D. GILCHRIST JR., BOBB CHANEY -

Class Notes

Class Notes1921*

December 1940 By CHARLES A. STICKNEY JR., ROGER C. WILDE

Charles Bolte '41

-

Article

ArticlePLAYERS' AMBITIONS CONTINUE UPWARDS

October 1939 By Charles Bolte '41 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

October 1940 By Charles Bolte '41 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

November 1940 By Charles Bolte '41 -

Article

ArticleSERIOUS CONCERN BELOW SURFACE

November 1940 By Charles Bolte '41 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

February 1941 By Charles Bolte '41 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

May 1941 By CHARLES BOLTE '41