Eye on Liberia

Daylight faded quickly as the presiding officer of the rural Royesville polling station unfolded each of the colorful ballots and presented the contents to the watchful eyes of the party agents and international observers. Last summer's Liberian election, the first since then-President: Samuel Doe's notoriously tainted 1985 poll, was coming to a peaceful end. As a member of the 40-person election observation team led by former President Jimmy Carter, I watched as the ballots showed warlord Charles Taylor winning in a landslide. I hoped this election would be the first step back from die abyss created by one of the most brutal civil wars in recent times.

I was assigned to Bonn county-, a war-torn area on the road to Sierra Leone. I arrived to find residents bubbling wit li cautious excitement at the prospect of voting. As in the Cambodian, election, where I worked as a U.N. electoral supervisor for the year leading up to that 1993 election, lines began forming at polling stations at midnight. The polls opened at 7 a.m. with an officer .turning a clear ballot box upside down. to Prove its emptiness. I hustled around the country, observing 23 of the 44 sites in Bomi count}'. By the time I slogged my way down the muddy road to Royesville, more than 750,000 Liberians had voted—-75 percent for Taylor.

Almost a year has passed since that counting session in the Liberian jungle. Back in the relative comfort of my New York office at Goldman, Sachs & Cos. I watch the media for any trace of news on Liberia. I cautiously, optimistically believe this election will work, that peace is sustainable. Liberia's democratic movement has taken its first baby steps.

Entwistle and Liberians worked for democracy

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

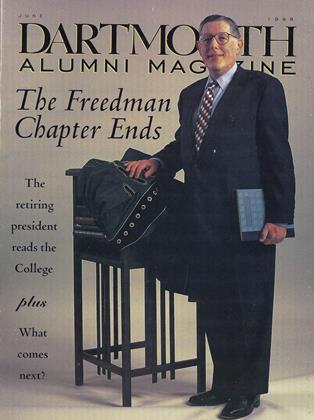

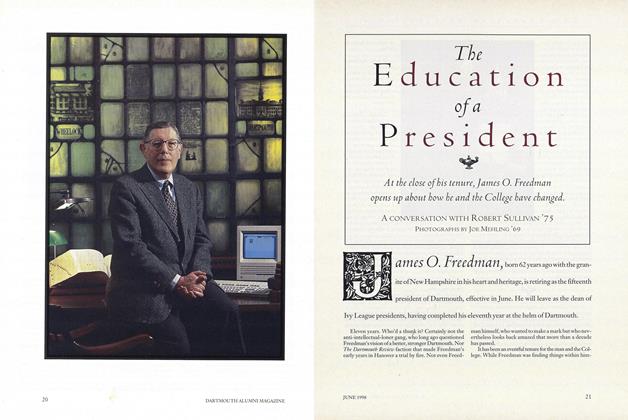

Cover StoryThe Education of a President

June 1998 -

Feature

FeatureWhat Comes NEXT

June 1998 By Charles Wheelan ’88 -

Feature

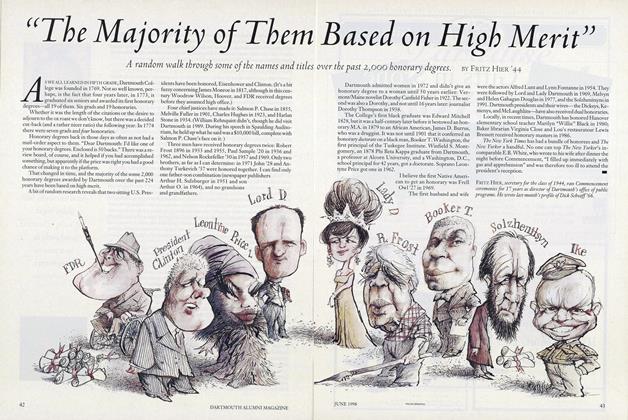

Feature"The Majority of Them Based on High Merit"

June 1998 By Fritz Hier '44 -

Article

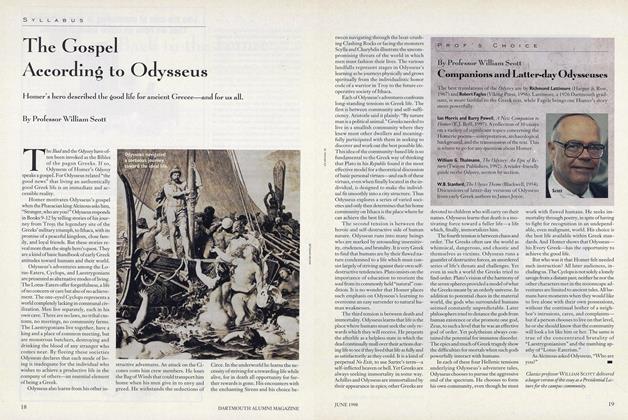

ArticleThe Gospel According to Odysseus

June 1998 By Professor William Scott -

Article

ArticleBack to the Future

June 1998 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleNewt ana Other Spring Speakers

June 1998 By "E. Wheelock"

Article

-

Article

ArticleEXAMINATION SMOKERS

February, 1909 -

Article

ArticleThayer Co-ed Students

January 1943 -

Article

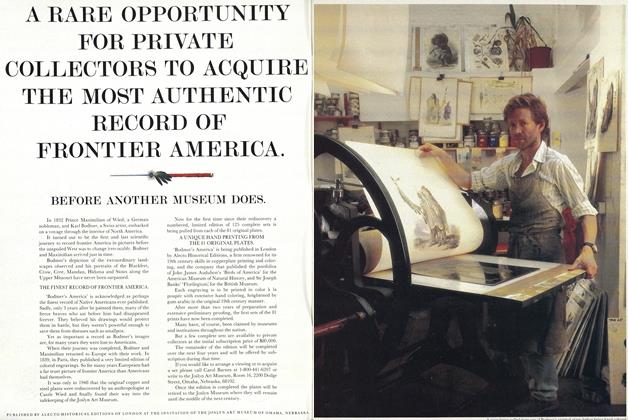

ArticleA RARE OPPORTUNITY FOR PRIVATE COLLECTORS TO ACQUIRE THE MOST AUTHENTIC RECORD OF FRONTIER AMERICA.

OCTOBER 1991 -

Article

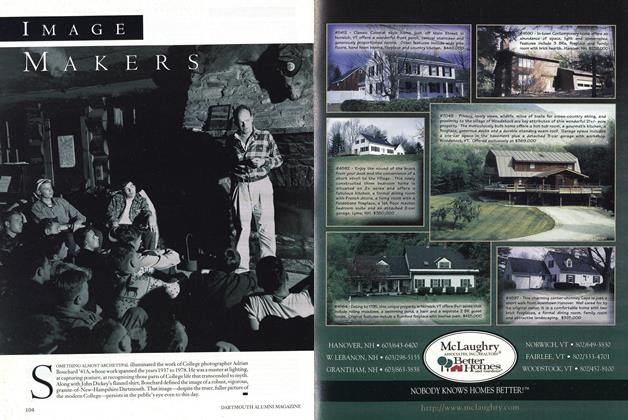

ArticleImage Makers

JUNE 1999 -

Article

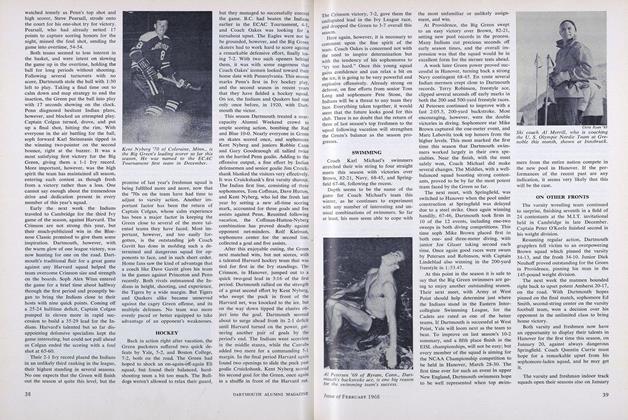

ArticleHOCKEY

FEBRUARY 1968 By ALBERT C. JONES '66 -

Article

ArticleMedical School

January 1947 By Rolf C. Syvertsen M.D.