By Theodore Geisel '25. Random House, 1940. p. 56.$1.50.

DESPITE SUPERFICIAL SIMILARITIES, the differerences between Henrik Ibsen and Theophrastus Seuss are systematic and basic. The fact that both are symbolists should not lead us into the easy supposition that there is any connection between their respective uses of symbolism as a literary armature. Nor should the fact that both are absurd on the surface insulate us against a realization that, whereas Dr. Seuss's absurdity stops short a few millimeters below the cortex, the absurdity of Ibsen goes right through to the core.

We who essay criticism should have the courage of our blind spots as well as the faith of our highlights; and I may as well admit that this comparison has been drawn between a fairly recent experience of The Wild Duck on the Hanover stage, and a quite recent reading of Horton Hatches the Egg. The two works, about equally funny, have drawn me into this disquisition on comparative symbolism because Ibsen's variety of symbol centers directly behind my critical, opaque eight ball, but Seuss's basks in the blissful, clear glare of the fluorescent lamp. Since early youth, I have been aggravated by an assumption on the part of my professorial betters that symbolism is something you can understand but cannot explain. They have said,

"Look! Wild Duck," and I have looked and asked, "So what?" and got nothing for my earnest curiosity but glances of profound pity. With Seuss it is wonderfully different. HortonHatches the Egg is a symbolic parable for our times, and the symbolism is as clear as day. The faithful elephant who sits on the egg of the faithless lazy bird has nothing whatever to do with Wendell Willkie. It is a staggering argument, rather, for holding firm to one's faith in first principles, in spite of the devil. It is, among other things, a parable against appeasement. Its crisis comes when Horton, faced by the rifles of the hunters (Munich for Horton) makes his great decision and goes right on sitting on that egg. And in the end, to confound pragmatic biology with transcendental morality, what hatches is not another little lazy bird at all. What hatches is—but read it for yourself, and remember that the way to attain the little winged pachyderm of happiness on earth is to stick to your principles, no matter who else is sticking to his guns.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

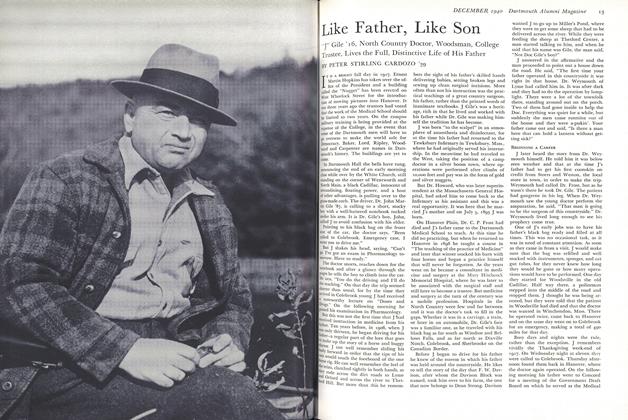

ArticleLike Father, Like Son

December 1940 By PETER STIRLING CARDOZO '39 -

Article

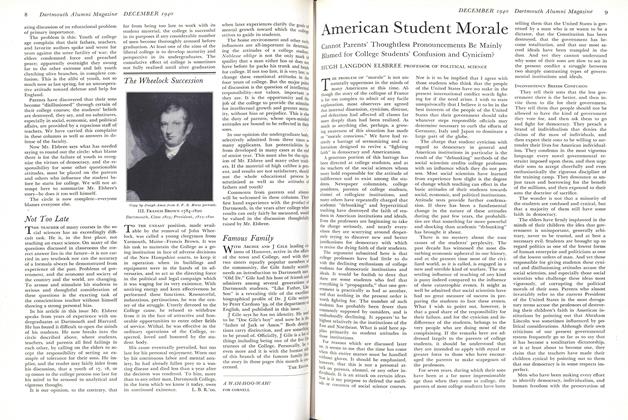

ArticleAmerican Student Morale

December 1940 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

December 1940 By Charles Bolte '41 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1917*

December 1940 By EUGENE D. TOWLER, DONALD BROOKS -

Article

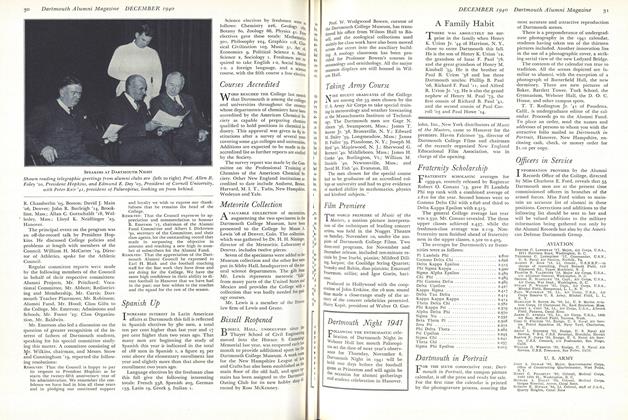

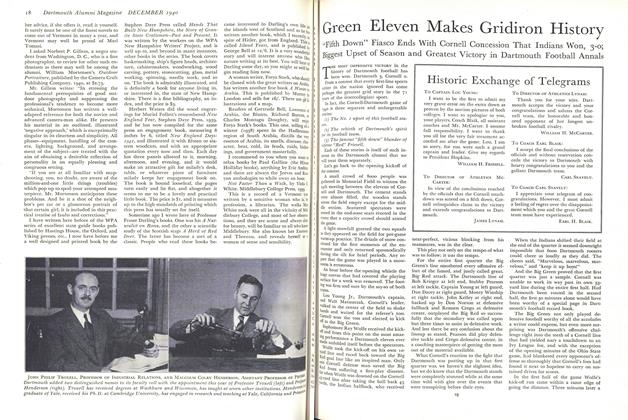

ArticleGreen Eleven Makes Gridiron History

December 1940 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1935*

December 1940 By JOHN D. GILCHRIST JR., BOBB CHANEY

Alexander Laing '25

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters

June 1940 -

Books

BooksTHE FIVE HUNDRED HATS OF BARTHOLOMEW CUBBINS

January 1939 By Alexander Laing '25 -

Article

ArticleHakluyt in Hanover

October 1939 By ALEXANDER LAING '25 -

Article

ArticleWILLIAM JEWETT TUCKER

November 1943 By ALEXANDER LAING '25 -

Article

ArticleCOLLECTED VERSE PLAYS.

JANUARY 1963 By ALEXANDER LAING '25 -

Books

BooksFITZ HUGH LANE.

MARCH 1973 By ALEXANDER LAING '25

Books

-

Books

BooksALUMNI PUBLICATIONS

November 1923 -

Books

BooksVolume XI of Collected Papers From the

November 1935 -

Books

BooksDEMOCRATIC GOVERNMENTS IN EUROPE:

October 1936 By A. H. Basye -

Books

BooksShips Underseas

May 1975 By LOUIS MORJON -

Books

BooksITALIAN ODYSSEY, AN EAR TO THE WIND.

OCTOBER 1969 By PENNINGTON HAILE '24 -

Books

BooksNIKOS KAZANTZAKIS.

OCTOBER 1972 By RUTH SYLVESTER