By EvanS. Connell Jr. '45. New York: The VikingPress, 1963. 390 pp. $6.00.

Authors once took it for granted that they should bring their works as close as they could to ultimate clarity and form. It is Freud's fault that devoted artists have lately been producing books like this one in which the final blending of subconscious and conscious elements becomes the reader's hard work instead of the writer's. Notes From aBottle ... draws material, explicitly or allusively, from the literature of exploration, both of the earth and of man's ferocious depravity. Its secretive organization might roughly be bracketed between the perverse jumble of Pound's Cantos and the exquisite riddle of Finnegan's Wake.

Connell begins with the Pater Noster in Latin, followed by sixteen explicit lines describing the slow dismemberment of Damiens; he puts a question in French and translates it, asks a question in English, makes a terse comment which has the flavor of a quoted religious aphorism, and then invites the reader to go - or else not to go - with the eels to the Sargasso sea. That is page 1. It poses the critical problem of the book. How many readers will think first of the martyr Damien, then remember Damiens the wishful regicide, to whose four-hour torture Casanova gave such ambivalent attention from a hired window? What is Connell's part, as author, in this passage? Is it a translation or a recreation? Is it "true," or warped to his purpose? What is his purpose? Such questions, which recur on all of the following 242 pages, will put the scrupulous reader to a bad choice. He can respond viscerally, ignoring the problem of artistic truth, or he can search out multitudinous sources that may show what his author is up to. Everyone will find hints here of episodes encountered in other reading. Although the island called Tile (page 29) is not to be found indexed in the Britannica, I by chance know of it and of the cleric (page 65) who misplaced it upon a fabulous map. Connell corrects the error of Olaus in his own text. But on page 3 he gives a prettified "translation" of the runes on the bogus "Kensington stone," with no hint of the source, or of the fakery. Was he taken in? Does it matter that his book may be a jumble of the valid and the spurious? Not if it has coherence, internal meaning, as a work of art. What then is its structure?

As the title frankly announces, it is a long string of notes, perhaps five or six to a Page, more than a thousand. A few threads appear and disappear like dolphins: the thread of abominable cruelty of man to man, scenes of intimate torture, recurrent scenes of the vast wickedness of Hiroshima, references to a dead brother. A vague sort of voyage is implicit: a dozen or more precise positions, latitude and longitude, that make no sequential sense. The longer notes seem all to be of a sort that one might identify if there were no more fruitful demands upon his time; they seem to have historical origins. Comments, exclamations, brief quotations, are interspersed, mostly in English but in half a dozen other languages. Here the quality of writing seems to me to vary from skillful to sententious. Other reviewers have raised the question, is it a poem? Several have said, no. I say that it contains some extraordinary poems, awash among the materials for others. Look on page 143 for a marvelous evocation of the soldier's return from war.

It may be that the whole book is a considerable work of art. It seems to me a half-finished assemblage of materials for something that might have been of major importance.

Poet, novelist, and teacher, reviewerLaing is Educational Services Adviserat the College

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

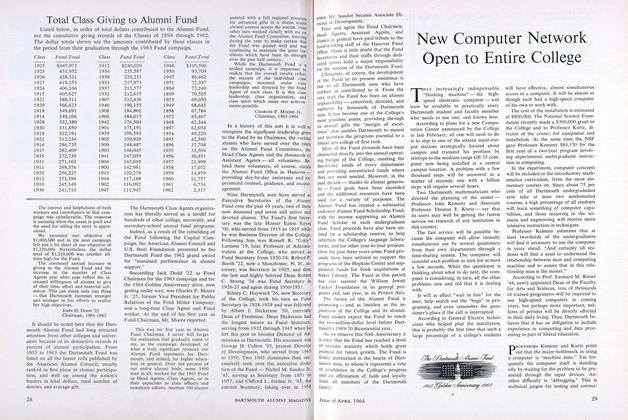

FeatureA BLUE-CHIP ASSET FOR 50 YEARS

April 1964 By HAROLD F. BRAMAN '21, CLIFFORD L. JORDAN JR. '45 -

Feature

FeatureOldest Living Graduate, Will Be 100 This Month

April 1964 By Dr. Edwin H. Allen '85 -

Feature

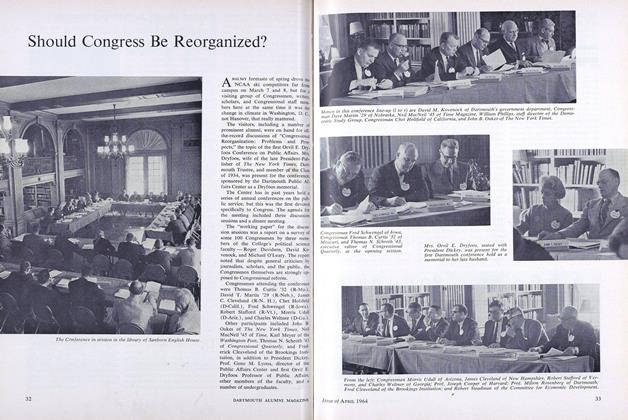

FeatureNew Computer Network Open to Entire College

April 1964 -

Feature

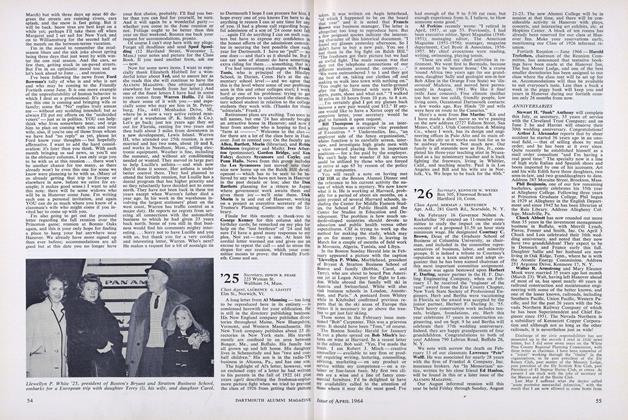

FeatureShould Congress Be Reorganized?

April 1964 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1926

April 1964 By KENNETH W. WEEKS, HERMAN J. TREFETHEN -

Class Notes

Class Notes1924

April 1964 By CHAUNCEY N. ALLEN, PHILLIPS M. VAN HUYCK

ALEXANDER LAING '25

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters

June 1940 -

Article

ArticleWILLIAM JEWETT TUCKER

November 1943 By ALEXANDER LAING '25 -

Books

BooksA MIRROR FOR AMERICANS. LIFE AND MANNERS IN THE UNITED STATES 1790-1870 AS RECORDED BY AMERICAN TRAVELERS.

January 1953 By ALEXANDER LAING '25 -

Article

ArticleVirtuous Pagan

January 1960 By ALEXANDER LAING '25 -

Article

ArticleBelinda

MARCH 1963 By ALEXANDER LAING '25 -

Books

BooksTHE STRIDE OF TIME.

APRIL 1967 By ALEXANDER LAING '25

Books

-

Books

BooksSHADOWS ON THE LAND — AN ECONOMIC GEOGRAPHY OF THE PHIL IPPINES.

MAY 1964 By ALBERT S. CARLSON -

Books

BooksSHAKSPERE, SHAKESPEARE AND

April 1938 By Anton A. Raven. -

Books

BooksBecoming Yankees

SEPTEMBER 1981 By David M. Shribman '76 -

Books

BooksWILD TRAIN: The Story of the Andrews Raiders

January 1957 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Books

BooksCOMBAT MISSILEMAN.

June 1962 By HOWARD F. EATON -

Books

BooksTHE PSYCHOLOGY OF EGO-INVOLVEMENTS,

April 1948 By IRVING BENDER.