No one has given a name to the "thirties" yet, but if we were asked to give it a title our vote would be for the "Limping Thirties" as a follow-up for the "Roaring Twenties." Ten years of reneging the things built up in the twenties, of fearing the educations given to American youth during the boom years, of disowning John Held Jr. and stowing the raccoon coats away in the moth balls, of wondering where the colleges were getting their ideas of liberalism but failing to look back into the previous decade when liberalism was the popular range like mahjong and the bond business—that was the gift of the thirties to the forties.

America came home from war and the drums beat a slower rhythm than the mar- tial airs which had sent it off. It was a rhythm for tired feet and disillusioned spirits, for a tired nation which found that the World War was not the inspiring and glamorous event which it thought it would be. It was not the romantic adventure of its fathers in the Spanish-American war, nor did it have the gallant charges of the Civil War that its grandfathers told about. The disillusion in stories of the past resulted in a reformation in education and traditional subjects were dropped from the curriculums of the country's colleges and universities. Latin and Greek lost their prestige and emphasis was placed upon practical knowledge that would conform with the boom sweeping America.

The stockbroker and the bond salesman, the bootlegger and the bookie, were riding along on the crest of a wave with the rest of America. Business was good and undergraduates had very little to worry about just as long as their checks were arriving on schedule. It was smart for the college man to be somewhat lax in his actions and, though many reformers clucked their tongues against the roofs of their mouths and said no good was going to come of petting parties in cars on lonely roads or of the hip flask, no one was particularly worried. It was the thing to do, and the flapper skirts crept higher, the two spots of rouge on the cheeks grew brighter, and the raccoon coats grew fuzzier. The era of reformation in education had brought with it a liberalism and ushered in the teachings of Trotsky, Lenin and Marx, but no one was worried about the fact that the undergraduates might become radical. It was simply a question of getting an education from all sides and only a few were worried about the unemployed, though everyone thought it was too bad that it had to be that way. There were enough students being educated under the new liberalism who didn't have time to consider what they were learning to off set the "dangerous influence of the liberals."

Affluence was everywhere and the colleges prospered, Dartmouth among them; then the Thirties brought in a crash that was almost as loud as Emerson's shot which was heard around the world. Pyramids of wealth tumbled down and the numbers of the unemployed went up and up. It was a depression which was to twist the "Roaring Twenties" into a contorted decade of worries and fear and insecurity. were only a few hangovers from the golden decade; the liberalism was still there, but it had grown bigger until it had become a strong social consciousness, replacing the blase era of the flapper and collegian.

It was then that the thirties showed themselves to be ten years of refutation. Those who had taught the younger generation its liberalism looked askance and wondered where it had learned such things, but didn't consider that it was an outgrowth of the break from pre-war thinking which began in the twenties. It was a liberalism that had developed when there was nothing to worry about, but was feared when times were poor at best. It was an age when un-American activities which had been overlooked in the twenties were investigated in the thirties. It was also the age when Browder was refused permission to speak at Dartmouth, while, in the previous decade, it was stated that even Trotsky himself could address Dartmouth from the speaker's platform as a proof of the College's wish for education from all sides.

Now, as the 1940's begin, there seems to be a back-pedalling on the Browder issue 011 the campus. It has been undercurrent talk which says, in essence, perhaps it was wrong not to have had him. Part of this feeling may stem from the fact that "the existing circumstances" which kept him from speaking two months ago are no longer so obviously existent, but most of the feeling may be attributed to a prediction that the Browder controversy will be known in the future years as an interesting commentary on the "Limping Thirties" and not so much as a righteous conviction on the part of the College administration that there was no point in asking Browder up to Hanover because there wasn't sufficient student interest.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleMore Than Professor

February 1940 By JOHN HURD JR. '21 -

Article

ArticleThe College In The Sixties

February 1940 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1915*

February 1940 By CHARLES R. TAPLIN -

Article

ArticleEducation Without Books

February 1940 By Davis Jackson '36 -

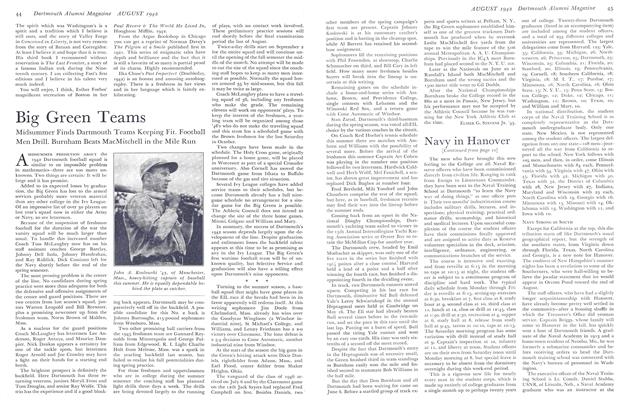

Sports

SportsBig Green Teams

February 1940 By Whitey Fuller '37 -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

February 1940 By HERBERT F. WEST '22

R. E. Glendinning '40

-

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

October 1939 By R. E. Glendinning '40 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

January 1940 By R. E. Glendinning '40 -

Article

ArticleRELATED TO HARVARD REFUSAL

January 1940 By R. E. Glendinning '40 -

Article

ArticleDAILY EXTENDS INVITATION

January 1940 By R. E. Glendinning '40 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

February 1940 By R. E. Glendinning '40 -

Article

ArticleABOUT THE CAMPUS

February 1940 By R. E. Glendinning '40