NEARLY EVERY speech dialect in the country gets voiced in the Dartmouth College Speech Clinic, where a year-round program is being carried out to correct the defects of students assembled from 47 different states. Foreign accents also mingle with southern drawls, New England twang, broad "A's" from the Boston area, and flat dialects from the middle west. In fact, one of the Clinic's major problems just now is a German student who wants to learn good English but who is wary of losing the accent of his fatherland.

As part of the program directed by the department of public speaking, every Dartmouth undergraduate has had his voice and enunciation tested. Reading tests are compulsory for entering freshmen each fall, while voice recordings are made by all students taking public speaking courses and by any others who want recordings made and are willing to pay a slight charge. By means of these tests and recordings, Carl D. England, director of the Clinic, and Almon B. Ives, his assistant, are able to single out the individual Dartmouth students who need help. Some cases are sent to the Clinic by other departments, particularly the English department, and special speech problems are often contributed by the undergraduate dramatic club.

The directors of the Speech Clinic have found that 65 per cent of the Dartmouth student body have no noticeable defect of speech, while 27 per cent have only slight difficulties, and the remaining 8 per cent need corrective training. The students needing treatment may be divided into three groups: those with bad voices, those with poor enunciation, and stutterers. Equipment for the careful examination of the nose and throat passages helps the Clinic to determine which of the students need medical or surgical attention. Among the students being helped by the Clinic this year, about one-fourth are serious cases of nasal, husky or infantile voices; another fourth are stutterers; one-fifth are inarticulate; and the remainder are lispers, have foreign accents, or are unable to make certain sounds. It usually takes three weeks to train a student to say "1" correctly, while "r" is much more difficult and often requires a year. Students who stutter seem to work hardest to overcome their speech defects. The case of which the Clinic is perhaps most proud is that of the undergraduate who stuttered badly when he entered Dartmouth as a freshman and who ended up by delivering one of the commencement addresses when he graduated.

Those who stutter are taught how to view their impediment objectively, how to relax, how to control their breathing, and in a series of speech situations of progressively increasing difficulty, how to acquire the self confidence needed for good rhythmic speech. A private practice room is provided for this training series.

For students who have normal physical equipment but bad habits of speech, the Clinic has two complete recording outfits enabling them to hear themselves, and with the aid of palatograms, mirrors, charts, and a clinician, to correct their faults. For those with normal speech and a desire to improve, which group comes largely from the public speaking classes, the Clinic has an Esterline-Angus stripchart recorder, which charts on paper the variation in fqrce in a given speech, and an Oscillagraph, which pictures voice quality.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleRich Man's College?

April 1940 By JOHN HURD JR '21 -

Article

ArticleMeet Bill Daniels—

April 1940 By CHARLES E. WIDMAYER '30 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1930*

April 1940 By Chairman, ALBERT I. DICKERSON -

Sports

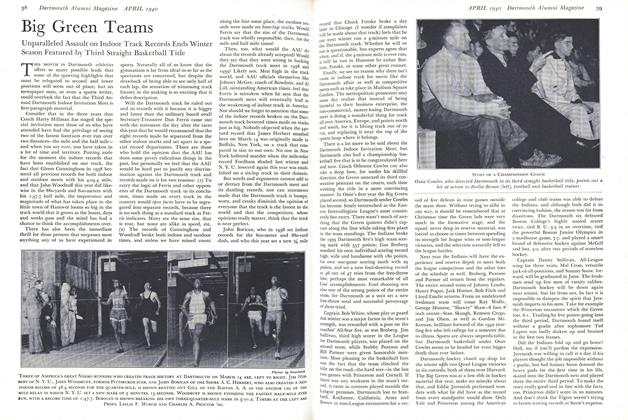

SportsBig Green Teams

April 1940 By Whitey Fuller '37 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1925*

April 1940 By Chairman, FORD H. WHELDEN -

Class Notes

Class Notes1938*

April 1940 By Chairman, CARL F. VON PECHMANN

Article

-

Article

ArticleFootball in Embryonic State

MAY 1927 -

Article

ArticleMasthead

May 1948 -

Article

ArticleTrustee Nominated

March 1949 -

Article

ArticleWith Big Green Teams

December 1956 -

Article

ArticleA scrum's-eye view of the ball during a rugby game this fall on Sachem Field. Winter Schedule

December 1961 By DAVE ORR '57 -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

January 1941 By HERBERT F. WEST '22