MY college friends and I have discussed whether or not racism penetrates the Dartmouth campus; we've argued about the kinds of sexism at our recently made co-educational school; we've pummeled each other with heavy discussions on abortion, God, love. Yet there has been a curious avoidance by us, and probably by most people, of a subject concerning the worst and most insidious "ism" of all, one that will affect everyone, black and white, male and female, at some time in our lives. Nobody ever talks about ageism, the set of attitudes prejudiced against the old.

Why should we think about it? A friend who is majoring in both philosophy and religion, someone I know who relishes reading Kant probably as much as going to a movie, told me, "I've never thought about getting old." Another friend said thinking about old age is "contrary to human psychology." Again and again I have encountered this unconcerned attitude among my classmates.

Why should we think about it? Here we college students are, taking our LSAT's and MCAT's, agonizing over the outcome of intense emotional relationships, planning for the immediate future as if we didn't have one. Career developers and magazine articles on "job-hunting say, "What do you want to be doing in your job ten years from now? Fifteen?" Our tunnel vision stretches only to age 40, if that far. But how long is this vision going to continue — until we find ourselves in that stage of life for which we are least prepared? Out of this inability to face the furthest reach of our personal futures comes an ignorance of what it will be like to be old. Out of this ignorance comes in turn the hellishly neglectful or ostracizing treatment of the old so common today.

One might say it's silly or even sick to expect a 19-year-old to think of 90-year- olds. Why should we young, vibrant beings who can "pull all-nighters" because our nerves and flesh are tough, or who glory in the feel of (occasionally) clear heads and Precisely muscled bodies feel any empathy with those who have already had their youth? One cannot even expect people at age 40 to ponder senility and senior citizenship (why are we so terribly afraid to say "old age"?). Yet do we insouciant children have to view old age with such horror that we thrust not only the prophetic image of ourselves away from our minds, but also the very real image of old people into sterile nursing homes.

Old age should be and sometimes is a contributory time, a summation of a full life. But for more and more people, it is becoming a tragedy of powerlessness, economic want, and bitter loneliness.

In my sophomore year I visited with my psychology class the state mental hospital in Concord, New Hampshire. My group visited the geriatrics ward. We braced ourselves for the trauma of seeing what we probably would become — no doubt some of us had never seen an extremely old person before. To dissolve apprehension, some jokes were forced about the "babbling biddies" we were soon to observe. Yet there, amidst the obviously mentally ill, was a smiling, gentle woman, who chatted intelligently with us while she knitted. She appeared neither mentally nor physically infirm. Apparently she had been put away simply because she was old. What "they" did to you when you got old shocked me infinitely more than seeing the physical consequences of being old.

Society fosters our misconceptions on aging by mandatorially neutralizing nearly everyone at age 65. The day before your 65th birthday you are employable; the day after, who wants you? We have the encyclopedia of myths about old people, from sexual incapability to incompetence to just plain crankiness. We have unholy nursing homes where our obsolescent culture commits the ultimate dismissal of the "obsolete." We are truly ignorant about what can be the glories of old age.

Some changes in our perception of what it's like to be old may be forthcoming. According to a recent syndicated story in the Knight newspapers, a study at Puget Sound Health Co-operative in Seattle, involving 2,500 people over a 20-year period, showed that a person's abilities do not decrease with age. The study indicated that while there is some lessening in math abilities, verbal comprehension skills either increase or remain stable as a person ages. One of the important observations made by the director of the study is that "old people don't want to be isolated. They want to know what's going on." Another sign of hope appeared last fall in an Associated Press story, which reported that some elementary schools in Maryland will soon be testing a guide to help children develop positive views of old people.

The public consciousness has been raised via the work of the Gray Panthers and their fight for rights for old people; and by personalities like pipe-smoking Republican Congresswoman Millicent Fenwick of New Jersey, elected some two years ago, who seems proud of her 66 years (which is not old, but I mention it because it's one year beyond legal old age); by Dorothy Day, still millitantly active for workers' rights in her seventies. And who could ever dismiss an octogenerian like working-legend Arthur Fiedler (so recently honored by the College with a degree in humane letters)? These people have been exemplars all their lives, but they have made sure we still need them.

Since it is often pointed out that even at tender college age we Dartmouth students will be the makers of tomorrow's world, perhaps our own inner fires will never diminish very greatly. But there still must be a change made in our views towards old age, so that positive thinking can help build better lives for the old. We may one day have the power to legislate change to help old people have a living worthy of the lives they have led. This change will come about, however, only if we demand to understand and combat ageism.

Perhaps, on our cosmetic campus, there is no need to force the issue of even being aware of ageism, both as perpetrators and eventual victims. After all, most of the faces we see are as unlived in as our own. Practically no one we know of has ever had to eat dog food because her social security check wasn't sufficient to buy human food. We may have some inkling of the shame it is to be old today, but we can always believe, as does Edgar in King Lear: "The oldest hath borne most, we that are young/shall never see so much nor live so long." Maybe we summer beings should all plaintively say, as one of my friends did, "I don't ever want to get old."

That's not the answer. We must accept the most forbidden of thoughts — "I, too, will be old. So what I am going to do about it, both for myself and for others?" — and then follow our passages in life vigorously. Then perhaps in our winters we will not be discontent — because we will be lions.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureA simple mental technique... A simple mental tech... A simple mental... A simple...

February 1977 By PIERRE KIRCH -

Feature

FeatureNever Let Go

February 1977 -

Feature

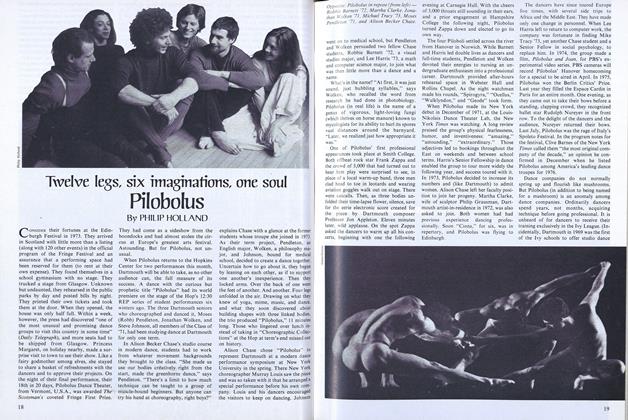

FeatureTwelve legs, six imaginations, one soul Pilobolus

February 1977 By PHILIP HOLLAND -

Feature

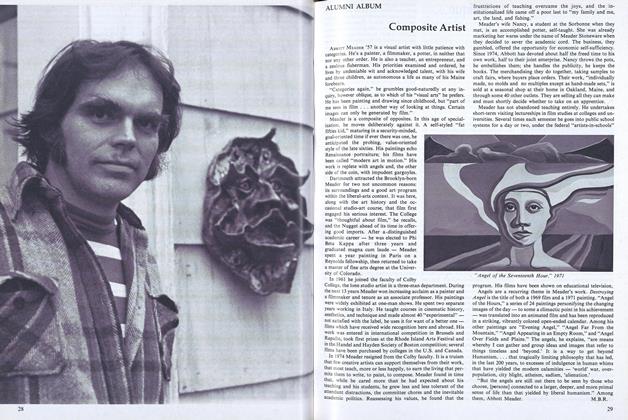

FeatureComposite Artist

February 1977 By M.B.R. -

Article

ArticleStepping Out with a Bounder

February 1977 By D.M.N. -

Article

ArticleBittersweet Memories

February 1977 By ROBERT J. ZOVLONSKY '58