Marcus Goodrich Took Ten Years to Write "Delilah," Turned Out a Fine Saga of Life in the Navy's Destroyers

IF YOU HAVE NOT YET READ Marcus Goodrich's masculine saga of a destroyer appropriately named Delilah you have missed one of the best novels of recent months. Anyone who has ever served in the Navy, or indeed the Army, will recognize the veracity and fidelity to character and atmosphere which Goodrich creates. The men are real, and if they are a little too boisterous at times, chalk it up to the American spirit. The real hero is the destroyer, and it is the kind of a boat which can, and does, demand and receive loyalty associated generally with ships in the days of sail. One feels somehow safer from foreign aggression than before he read the book.

You have undoubtedly read the reviews. They were all favorable and as they were full length I need not go into details here. Goodrich has read Conrad, and his psychology is American and not Slavic, but otherwise the comparison is a fair one. He does get under the skin of his characters and before you are through you will feel that you know them all well from the wild Irishman O'Connel (with the silver plate in his head) to the introspective Warrington. You will know the boat, too, and what officers think of politicians (how glad they must be with F. D. R. as their Commanderin-Chief), and you will live through brawls reminiscent of Paul Bunyan, and you may even know more about women, though there are none featured in the novel. You will once again feel a boat rolling under your feet, you will smell the hot oil in the corridors, and you will feel the throb of the engines driving the thin shell of steel along: a small monster of destruction.

Goodrich, it is said, took ten years to write his book. As it is a first novel one can well understand. I hope he has the success he deserves, and I hope, too, that the second volume will not be delayed more than a few years. I couldn't stand waiting ten for it.

There follow notes about a few books you may well have missed.

John Brunton's Book, Cambridge at the

University Press, 1939.

This is a diary now published for the first time of one of England's greatest engineers during the whole 19th century. John Brunton lived from 1812 to 1899, and worked in England, in the Crimea, and in India. He was a man of action, and of few words, but those that he favors us with are all worth while, and make this a fascinating and unique little book, which I read at a sitting. There are 160 pages.

The Youngest Disciple, by Edward Thompson. Faber & Faber, London, 1938.

This is a study of Buddha based on tradition and Buddhist scriptures, pictured with an amazing fidelity to the background of early India. His life and good works are seen through the eyes of a shepherd boy who becomes a convert. This book is obviously not for everybody, but I have long believed in Edward Thompson. Believed, that is, that he is one of the finest writers in England. I have more than a dozen of his books, which include his Collected Poems.

The Road to Santa Fe, by Stanley Vestal. Houghton, 1939.

Similar to Vestal's other western studies: superficial but entertaining. Most of it has been told before.

Tuntiellers, by C. G. Grieve and Bernard Newman. Jenkins, 1936.

I just got around to reading this study of the sappers and miners of that long ago war, 1914-1918, whose biggest feat was the blowing up of Messines Ridge in 1916. Now the boys blow up whole cities, which clearly indicates the truth of the idea of progress.

The Book in America: A History of theMaking, the Selling, and the Collectingof Books in the United States. By H. Lehmann-Haupt. R. R. Bowker Company, 1939.

Books from the Colonial times, 1638, to the present. For the expert. Escape With Me, by Osbert Sitwell.

Macmillan, 1939.

This is a magnificently written travel book by one of the Sitwells telling of a trip to Indo-China (Angkor Wat), and Peking. I had never read anything by Osbert Sitwell before, but this has sent me to his other books, for he is a first class prose writer, and has plenty to say that is worth saying. The book is well illustrated.

Wild Chorus, by Peter Scott. Country Life (probably Scribner's in America), 1939.

21 shillings.

Peter Scott, son of the late Captain Robert Falcon Scott, has become England's most famous painter of ducks and geese. This book, written and illustrated by him, tells of his lighthouse home on the East Coast of England, of his hunting, and of his great love for ducks and geese. The illustrations, many in color, are really suberb.

I read Anne Morrow Lindbergh's TheWave of the Future with the respect due to a brilliant and honest young woman but she failed to convince me. I agree, of course, that there is a Revolution on, but I disagree (1) with her contention that we are not in the war (I believe we have been in it almost since it started), and (2) with her ideas about the Germans. She fails to take into account their flair for delusions of grandeur, for messianic complexes, for mistiness of thinking (as contrasted with the Latin spirit). Nor do I see how any one can, as Herbert Agar reminded us some months ago, simply lie in the ditch and let the "Wave of the Future" roll over us, especially when the wave is a Nazi one. It seems to me that we must go and meet it and ride its crest whether it takes us East or West. Or even North or South.

The Camera Craft Publishing Company has recently published a book for photographers on How To Build if Equip a Modern Darkroom, by Nestor Barrett and Ralph Wyckoff. There are many illustrations, and I am very sure that if anyone wants to build a darkroom he could do so with perfect equanimity after reading this book. I hope that the darkroom may conveniently be changed into a bomb shelter, although for the moment it may be used for films.

The Fire Ox and Other Years, by Suydam Cutting. Scribner's, 1940.

This is a handsome travel book describing many year's travel in Turkestan, Assam (headhunters), Nepal, Tibet (Lhasa), Andaman Islands, Galapagos, Upper Burma, Ethiopia, and Celebes. There is a fine account of cheetah hunting, etc.

I believe that Mr. Cutting is now doing British Relief work in New York City.

The Crazy Hunter, by Kay Boyle. Harcourt, 1940.

Many people find Kay Boyle unintelligible, but for those who don't this is a fine book written with most delicate feeling for her characters as well as for the perfect phrase. The book is composed of three long-short stories. I am not sure that I didn't enjoy the simplest of the three the best which was "Big Fiddle," the story of a young man who got into a terrific jam from which he is unable to extricate himself. It might have happened to any one of us. She writes of the terrors which haunt the souls of all people of subtle comprehension, and so with Katherine Anne Porter, with whom she has a lot in common, Kay Boyle can write only for the comparatively few. Nevertheless she is one of our few talented writers: One of our best.

If you have not yet read I Rode withStonewall, by Henry Kyd Douglas by all means do so. Chapel Hill publishes this book written by one of Stonewall Jackson's staff, and who, were he living today, would be a hundred years old. His book has been lying in manuscript for nearly forty years. This is the first edition, and is a book to own. They, too, had their wars!

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleThe Dartmouth College Eye Institute

June 1941 By C. E. Widmayer '30 -

Article

ArticleA Versatile Engineer

June 1941 By Edwin A. Bayley '85, William P. Kimball '28 -

Sports

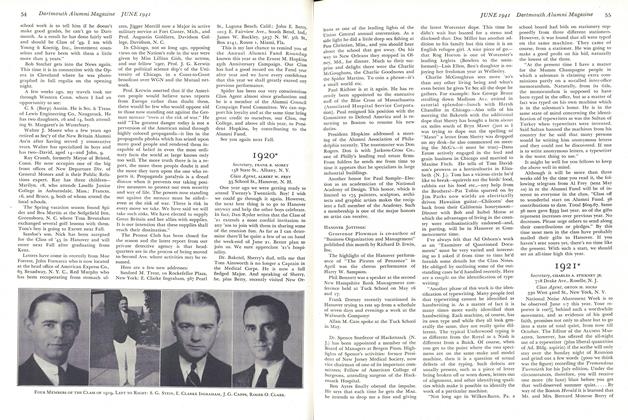

SportsBig Green Teams

June 1941 By Whitley Fuller '37 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1921*

June 1941 By CHARLES A. STICKNEY JR., ORTON H. HICKS -

Class Notes

Class Notes1929*

June 1941 By F. WILLIAM ANDRES, VAN NESS JAMIESON -

Class Notes

Class Notes1917*

June 1941 By EUGENE D. TOWLER, ARTHUR P. MACINTYRE

HERBERT F. WEST '22

-

Books

BooksWHEN WE SKI

April 1937 By Herbert F. West '22 -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

October 1948 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

December 1949 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

April 1957 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

November 1957 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Books

BooksCELEBRITIES AT OUR HEARTHSIDE.

June 1960 By HERBERT F. WEST '22