The Story of an Increasingly Renowned Research Center Contributing Much to the College and Outside World

DARTMOUTH ALUMNI and others acquainted with the undergraduate character of the College are sometimes puzzled over the anomalous location in Hanover of the Dartmouth Eye Institute, one of the nation's outstanding research and clinical centers in the field of physiological optics. Several years back they might have been surprised to learn that the Institute even existed at Dartmouth, but any such surprise today would indicate pretty clearly that they had not kept up with the scientific news of the day. For despite all self-effacing efforts to stick quietly to its job, the Institute has attracted wide attention through newspapers and magazines on the alert for important scientific developments and has been sought out by suffering persons from nearly every state in the land and even from abroad.

Discovery of the eye defect aniseikonia and development of methods for diagnosing and correcting it have been the Institute's most significant contribution to ophthalmology to date and have at the same time been the major reason for its growing reputation. But the investigations of the Institute have always been much wider in scope than is generally known and have, in the words of a staff member, been aimed at advancing "through research, basic scientific knowledge and clinical scientific knowledge concerning the diagnosis and treatment of all kinds of defects and anomalies in the field of vision." These investigations have recently opened up new avenues of study with exciting possibilities of benefit to modern man, and, given the means to develop this broader program, the Institute will almost certainly bring still greater credit to itself and to the College.

Behind the Institute's present status in the research world stretches a long story of evolutionary growth from small beginnings. The tale goes back to 1919, when Adelbert Ames Jr., present head of the Institute's research division, first came to Hanover to seek the help of Professor Charles A. Proctor 'OO of the Dartmouth physics department; or to be entirely accurate, it goes back even farther to 1910, when Mr. Ames gave up his Boston law practice for painting, an avocation which gradually involved him in the visual aspects of art appreciation and ultimately in the study of physiological optics. He sought out Professor Proctor with the problem of measuring the characteristics of the eye as a camera and was welcomed to Dartmouth and given working space on the top confloor of Wilder Hall. The College recognized his successful work two years later by electing him Professor of Research in Physiological Optics and awarding him the Master of Arts degree.

Meanwhile, Gordon H. Gliddon, staff member of the lens-designing division of the Eastman Kodak Company, desired to increase his knowledge of physiological optics and came to Hanover in 1923 as a graduate student. His thesis subject was "An Optical Replica of the Human Eye." Word got bruited about the Dartmouth campus that the group in Wilder Hall was working on a glass eye to be connected to the brain and that this invention would startle the world. Among the instruments developed to measure the various optical properties of the eye was a rather complicated one referred to as "The Thing" and later christened "The Spirit of Hanover."

One day a person who had suffered with intractable headaches was examined, on the suspicion that the trouble might be caused by an obscure eye defect, and was given relief through the discovery and successful correction of the cyclophoric defect. This was the actual beginning of an eye clinic at Dartmouth. At this stage Dr. Henry Lyman and Augustus Heminway of Boston provided funds so that further research could be undertaken, and Mr. Gliddon, who had now completed his doctorate, joined Mr. Ames as Research Fellow in Physiological Optics. Other graduate workers were added, among them Kenneth N. Ogle of the Dartmouth physics staff, and knowledge of the research program began to spread. As the work broadened and quickened its pace, an increasing number of patients were examined and treated, making the top floor of Wilder Hall virtually a clinic as well as a research laboratory.

The simultaneous development of research and clinical investigation has been an outstanding characteristic of the Dartmouth Eye Institute from the very outset. That the two divisions have progressed without the slightest friction and have dovetailed their work toward a common objective is a propitious factor in the past and present success of the Institute. Although clinical practice has been carried on as contributory to the fundamental research purposes of the Institute, the clinic has been a tremendously important and beneficial division in itself, and its earliest emergence made logical the transfer of control of the whole physiological optics program from the College physics department to the Dartmouth Medical School. Work had progressed, in fact, to the point where in 1928 a first report was warranted before the ophthalmological section of the American Medical Association, which awarded the Dartmouth department the bronze medal for "significant application of physics and physiological optics to ophthalmology"

The influx of patients began to tax both the personnel of the Department and the research quarters in Wilder Hall. At this critical juncture John D. Rockefeller Jr., who had become interested in the work, came forward with a generous gift which made it possible to increase the staff and assure the continuance of the work for a five-year period. Leo F. Madigan was brought from New York to assist in the clinical division and Dr. Elmer H. Carleton came from Hanover's Hitchcock Clinic as an associate on the clinic staff. Mr. Ogle, whose graduate studies had contributed materially to the research program, was appointed a Research Fellow. Further progress was made possible by George Agassiz of Boston, who contributed funds for use in the clinical division.

These developments gave real impetus to the work. More and more persons were given eye examinations on the instrument now called the ophthalmo-eikonometer (eye and image measurer), resulting in the discovery and actual measurement of more and more variations in ocular images. The Department was here advancing into an unexplored field and making scientific study of a defect in binocular vision previously disregarded. The ocular image, as most readers know, is defined as the picture carried to the brain by the optic nerve after the image formed by the lens system of the eye has been focused on the retina in the back of the eyeball. In eyes which are functioning correctly the two ocular images are alike and fuse together to appear as one. In eyes in which the images differ in size or shape such fusion is difficult or impossible and is often accompanied by false space perception, nerve strain and fatigue. In extreme cases the brain as a last resort may suppress one image and turn that eye out of line. This nerve strain may show itself in such a variety of ways that some of the symptoms might not be suspected as coming from the eyes at all. Headaches, dizziness, nervousness, trouble with bright lights (photophobia), sleepiness when reading, burning or itching eyes, not seeing things where they really are, and fatigue when in the movies or when riding in a train or auto have all been found in certain cases to have been the result of difficult fusion of the ocular images. On top of all this, the defect is not necessarily associated with poor vision; it cannot be detected by the most careful refractive examination; and it appears only when the two eyes are examined simultaneously on an eikonometer. Before the Dartmouth Eye Institute delved into the problem many a sufferer had wandered from examination to examination without relief, only to be finally classified as neurotic and without any real defect.

This defect of unequal ocular images is the aniseikonia which is now so generally associated with the Dartmouth Eye Institute. Its name, derived from the Greek, was given to it by Dr. Walter B. Lancaster, the eminent Boston ophthalmologist who has recently come to Hanover as the Chief of Staff of the Institute. Along with ophthalmoeikonometer, the name of the testing machine, the adjective iseikonic describing the corrective lenses developed by the Institute is still another term added to the ophthalmologist's vocabulary as a result of the Dartmouth investigations. The earliest iseikonic lenses were "fitovers" clipped on over the regular glasses, and the first wearers in Hanover were the subjects of the unabashed scrutiny and joshing which flourish on any college campus. Since then, however, a unit lens has been perfected with the cooperation of the research staff of the American Optical Company, and glasses for the correction of aniseikonia now look like any other glasses. With the additional work on lenses the Wilder Hall quarters passed their saturation point and the clinical division of the Department moved temporarily to the Mary Hitchcock Hospital.

Recognition of the accomplishments of the Department of Research in Physiological Optics was slow in coming, as is usually the case with all such new developments. Two papers on aniseikonia were presented in 1931 before the American Academy of Ophthalmology and Otolaryngology at French Lick, where an early model of the ophthalmo-eikonometer was demonstrated, and in the following year members of the Department gave four papers before the New England conference of optometrists in Boston. At the latter meeting the Department was presented a gold medal for its distinguished service to optometry.

The American Optical Company meanwhile continued its cooperation with the Dartmouth group in developing new lenses and instruments and accepted the responsibility for making available ophthalmo-eikonometers for use in other clinical centers. By 1934 the installation of these instruments in clinics in New York, Boston and St. Louis had made imperative the establishment of a training course in the technique of using the ophthalmo-eikonometer, and there began at that time the program of training clinicians which now constitutes a third major division of the Institute along with research and clinical practice. Dr. Henry A. Imus, who had been an aniseikonic clinician at Harvard for two years, joined the Dartmouth staff in 1934 to assist Mr. Madigan and Dr. Carleton in the operation of the two instruments at the Hanover hospital. At that time the staff numbered twelve members, all working with remarkable coordination of research and clinical efforts.

One is justified in thinking of 1934 as the dividing line between the first and second periods in the evolutionary growth of the Dartmouth Eye Institute, for in that year the late Dr. Alfred Bielschowsky, eminent German ophthalmologist, began his association with the Department. Formerly Professor of Ophthalmology and Chief of the Eye Clinic at the University of Breslau, Dr. Bielschowsky came to Hanover in November, 1934, to undertake six months of special work with Professor Ames and his associates. A world authority in the field of ocular motility, his arrival immediately increased the significance of the work of the Department and, as it turned out, greatly accelerated the more inclusive research program toward which the Dartmouth group had been gradually working its way. Dr. Bielschowsky's sixmonths visit led to his appointment as Visiting Lecturer in Physiological Optics, and in 1937 he became Professor of Ophthalmology and Director of the Eye Institute. While the earliest research of the Department had dealt with monocular vision, and the work of the six years prior to 1935 had been devoted almost entirely to binocular vision as related to aniseikonia, the Institute now undertook far-reaching investigations designed to discover more about the relation of anomalous ocular incongruities and eye disturbances about which ophthalmologists had little or no certain knowledge. One new line of investigation still being carried on and having special value today in the field of aviation, had to do with binocular spatial sense.

Although stimulating to broader investigation, Dr. Bielschowsky's work was more directly related to the clinical activities of the Department. With his addition to the regular staff the clinic immediately enlarged the dimensions of its practice, and the need for new quarters was met in the fall of 1935 by transferring the clinical division from the Mary Hitchcock Hospital to the white frame building at 4 Webster Avenue, its present location. Robert E. Bannon joined the Department at that time as Research Assistant, to be promoted soon after to Clinical Fellow, and in the following year Dr. Hermann M. Burian came as Visiting Research Fellow, joining the clinical staff in 1937 as ophthalmologist. From 1935 until his untimely death in January of 1940, Dr. Bielschowsky brought increasing distinction to the Dartmouth Eye Institute, directing the clinical practice, contributing to the research program guided by Professor Ames, and lecturing throughout the country before medical schools and ophthalmological societies. It was during this regrettably short period that knowledge of the Institute's work became widespread and that the broad outlines of the Institute's present-day program were clarified.

The present organizational lines of the Institute were also established in 1937, when the Board of Trustees of the College voted that the Department of Research in Physiological Optics should thereafter be known as the Dartmouth Eye Institute and that control, under the Dartmouth Medical School, should be vested in a board of directors. The first board was headed by Dean John P. Bowler 'l5 of the Medical School and included Professors Ames, Bielschowsky and Gliddon; Halsey C. Edgerton 'O6, Treasurer of the College; Max A. Norton 'l9, president of the Mary Hitchcock Hospital; Dr. John F. Gile 'l6, of the Hitchcock Clinic staff; and Dr. Ralph E. Miller '24, of the Medical School. On May 1, 1940, John Pearson 'll, formerly Director of the New Hampshire Foundation, resigned his post as New England regional director of the U. S. Social Security Board to become Executive Director of the Institute, serving as administrative head of the research, clinical and training divisions. Six months later Dr. Lancaster, who had long been actively interested in the Dartmouth eye investigations, came to Hanover as Chief of Staff. Dr. Lancaster's formal association with the Institute brought into the Dartmouth group the dean of American ophthalmologists—an outstanding eye authority who had formerly been president of the American Ophthalmological Society, the American Board of Ophthalmology, and the American Academy of Ophthalmology and Otolaryngology, and head of the Section on Ophthalmology of the American Medical Association.

This, with various additions bringing the staff up to thirty-five members, is the present organization of the Institute. With the exception of Mr. Pearson in place of Dr. Bielschowsky, the membership and control of the board of directors has remained unchanged since 1937. The research division is now carrying on its work in historic Choate House, to which it moved from Wilder Hall in the fall of 1939 after conducting some of its special studies in the basement of McNutt Hall. The research staff of six members and seven assistants now includes Professor Ames, Professor Ogle and Dr. Imus of the early investigators, and among the newer workers Professor Irving E. Bender of the College psychology department, Camilla Hinton, and John W. M. Rothney, consultant from the University of Wisconsin. The clinical staff, headed by Dr. Lancaster, has four other ophthalmologists in the persons of Dr. Carleton, Dr. Burian, Dr. Arthur Linksz, who came from Budapest in 1939, and Dr. Kenneth L. Roper, who joined the staff last month. Its clinicians are Mr. Madigan, Mr. Bannon, Wendell Triller, and Rudoph T. Textor. In addition to Miss Lorna Billinghurst as orthoptic technician it also has two opticians and seven clinical assistants. The training division is now under the direction of Professor Gliddon, assisted by Mr. Madigan. The fields represented by the Institute's personnel include physics, optics, physiology, psychology and medicine.

The clinic, it can be seen, has grown into the largest division of the Institute; in fact, the influx of patients from all over the country, following the appearance of newspaper and magazine articles and the warmer commendation by word of mouth, has become so great that the Institute has recently been forced to protect its fundamental research purposes by adopting a restrictive policy toward new patients. So that new cases will provide the clinic staff with only the difficult problems of binocular vision with which its research program is concerned and will no longer provide the multitude of comparatively simple cases of eye strain which can be treated adequately by the general practitioner of ophthalmology, the Institute now accepts only new patients who are referred to it by physicians or optometrists. Patients previously treated will still have direct relations with the clinic, without referral, as will members of the College community. The Institute was reluctant to make this change in policy, but it decided that it would have to run the risk of some misunderstanding of the paradoxical truth that the public welfare would best be served by stricter selection of patients. The change has already reduced some of the pressure on the clinic staff and as time goes on it will undoubtedly enable the Institute to utilize more fully and more effectively the unique assets which it has for optical research.

Time is one of the research worker's priceless aids, and it is particularly important that the Dartmouth Eye Institute should conserve it, for the work on anomalous incongruities of the ocular images has opened up so many promising lines of investigation that the big problem is to select the most fruitful ones. Among these are studies leading to advancement of the basic knowledge of vision, especially of space perception, concerning which a great deal, strangely enough, remains to be discovered. In the clinical field the staff is eager to learn the answers to a lot of questions, especially those having to do with the relations between ocular image incongruities and such things as squint, the direction of one's gaze, ocular motility, fusion, accommodation, refractive errors, fatigue, phorias or fixation disparities, and the change of pupillary size with varying illumination. The aniseikonia tests, in addition, can be simplified and improved. The Institute is devoting a great deal of its attention at present to space perception, and until just recently it has participated in tests at the U. S. Naval air base at Pensacola, Florida, where examinations have been conducted to determine the relation between space sense and flying ability. The Institute has also given its special tests to commercial airline pilots at Kansas City, Mo., and at the present time it is doing research work in the field of vision for national defense. Since simple stereoscopic tests do not disclose how effectively the subject is using his eyes, the Dartmouth Eye Institute has devised for the first time tests which indicate whether the subject sees things where they really are. This one comparatively new line of investigation could easily absorb the major part of the energies of the Dartmouth staff, but other problems crying for solution must be tackled too.

One of the particularly interesting studies carried on by the Dartmouth Eye Institute, in conjunction with the psychology department of the College, has recently been completed and a final report is due this year. This project, directed by Dr. Imus, is a study of the relationship between visual defects, including aniseikonia, reading disabilities and scholastic standing. The study began in 1936, when eye examinations were given to all 636 members of the entering Class of 1940, and continued throughout the next four years as more complete visual tests were given to members of the class. At the same time a speeded reading program was established by Professor Robert M. Bear of the psychology department, in association with the Institute's project. More recently, Professor Bender of the same department has studied the importance of motivation in scholastic attainment and in other college activities. Among other questions which the study hopes to determine is an evaluation of compulsory eye examinations at the beginning of the college course in terms of more effective scholastic work. A preliminary report in 1938 indicated no definite relationship between ocular defects and reading disability, but 58 of the 76 freshmen whose visual defects were corrected reported later that their reading ability and their scholastic work had improved. The final report is being awaited with interest because it is regarded as of great importance in the fields of psychology and education as well as in the correction of visual defects.

PUBLIC INFLUENCE WIDESPREAD

In this case, as with aniseikonia, space perception and all its work, the findings of the Dartmouth Eye Institute have wide application to the public good. Recent years have seen a marked growth in the public influence of the Institute, directly through its clinical patients and indirectly through papers and lectures by staff members, seminars for professional ophthalmologists, training courses for technicians, and associated clinics which now exist in widely scattered parts of the country. The increase in patients is striking evidence of the Institute's growth. Starting with ten patients in its Wilder Hall laboratory in 1926, the clinic treated 4,796 persons in 1937, nearly 6,000 the following year, and last year examined 8,068 persons. During that period patients have come to Hanover from fortyfour states and also from England, Canada, South America, Honolulu and Australia. Last February the Reader's Digest reprinted an article about the Institute which had appeared earlier in Cosmopolitan magazine, and within a few weeks thousands of inquiries had been received from persons who felt that aniseikonia tests might provide the answer to their physical troubles.

Fortunately, most of such inquiries can now be referred to other clinics which are being set up throughout the country by clinicians trained in Hanover. Such clinics are serving patients in Boston, New York, Baltimore, Washington, Pittsburgh, St. Louis and San Francisco, and negotiations are under way to establish similar clinics in Hartford, Atlanta, Cleveland, Chicago and Colorado Springs. Besides its courses for clinicians the Institute is conducting weekly seminars for professional ophthalmologists of New England, and knowledge of its important researches is being spread throughout the medical world by means oi the steady preparation of scientific papers and lectures. Some sixty-eight papers in all had been written by staff members from 1921 through last year, and all but four of these had been distributed widely as reprints. Even the commercial world has felt the influence of the Institute's research, leading to collaboration with General Motors and the Libbey-Owens-Ford Glass Company in the designing of automobile windshields and windows that would minimize distorted vision. Other work has been undertaken with the United States Navy, the Civil Aeronautics Authority, the Massachusetts Association for Mental Hygiene, and the Committee on Scientific Aids to Learning.

The size and financial means of the Dartmouth Eye Institute are far from being in direct proportion to this considerable public influence. Present facilities, in fact, are a considerable hindrance to the ambitious and significant research plans of the staff; new quarters are a pressing need. Not only are the research and clinical divisions housed in two separate buildings, both makeshift and small, but also the clinic is inconveniently distant from the hospital where operations are performed. Tentative plans for a new building have been drawn by J. Fredrick Larson, the College architect, bringing all divisions of the In. stitute into a single unit. The cost of the new plant and equipment has been estimated at $150,000, a sum sufficiently large to shelve the building plans for an indefinite time. Since these plans were drawn several years ago the work of the Institute has expanded to such an extent that even this sum might now be insufficient to build the required quarters. Meanwhile, despite its cramped and inadequate quarters, the Institute carries on with research work that is not duplicated anywhere else, hoping that some foundation or individual benefactor will come to the rescue. Its assets cannot be considered negligible, even so, when one takes into account, as partial inventory, the Institute's association with Dartmouth; its Hanover location, conducive to calm, sustained work; its ever-widening recognition in the scientific world; its advantageous correlation with the Dartmouth Medical School and the Mary Hitchcock Hospital, both staffed with recognized medical specialists; and its access in Baker Library to one of the finest ophthalmological libraries in the world. This Baker Library collection was greatly enhanced in value and scope by the addition of all the books and reprints from Professor Bielschowsky's exceptional private library in the field of physiological optics.

ROCKEFELLER SUPPORT GENEROUS

While these assets are directly related to the College in the main, financial support of the Institute's work has come largely from outside Hanover. John D. Rockefeller Jr. and the Rockefeller Foundation have been generous in their support over a period of eleven consecutive years, and the American Optical Company and a number of individual benefactors have contributed substantially to the research program. To say that financial support has come primarily from outside sources is not to minimize the fact that the College has devoted many thousands of dollars from general funds to the work of the Institute. The College handles the Institute's finances in the general College budget, covering operating deficits as they occur, but the demands of the undergraduate departments upon the limited funds available are too great to permit the fuller support which the Institute deserves and which the College would like to give it. The whole financial question, in fact, has become critical with the approaching termination of the present Rockefeller Foundation grant. The continuation of the Foundation's support for six years, following five years of contributions from Mr. Rockefeller personally, has been somewhat unusual, and now that the Dartmouth Eye Institute has passed the experimental stage and has demonstrated the practical value of its work, the Rockefeller Foundation expects it to seek funds from other sources. The need for funds has been constant and increasingly urgent, and the financial questions which the board of di- rectors is now forced to face are difficult ones, particularly at the present time. What the board would like to obtain, even more than new quarters in which the staff can work conveniently and efficiently, is an endowment fund that would lay the finan- cial spectre for once and all. Present con- ditions have not engendered any false optimism in the minds of the board, but on the other hand neither do they see how the already proven public good of the Institute will allow it to do anything but go on to greater accomplishments.

These are serious problems which form a necessary part of the complete Eye Institute story, and it is a temptation, in conclusion, to dismiss them and to conjure up a roseate horizon of future promise for the Institute. Such an ending would have the rare virtue in this case of being justified, but it is already implicit in the story which has gone before, and one instinctively prefers to write about the Institute in the modest dimensions which it now actually has. The "story" resides, after all, in the contrasting results of great public benefit which have come from small and solid beginnings. Dartmouth alumni and others may still be surprised at what has taken root and grown up in the undergraduate soil of the College, but once they know the story they can have but one reaction and that is pride and satisfaction in what the Dartmouth Eye Institute is and in what it is contributing to the College and the world at large.

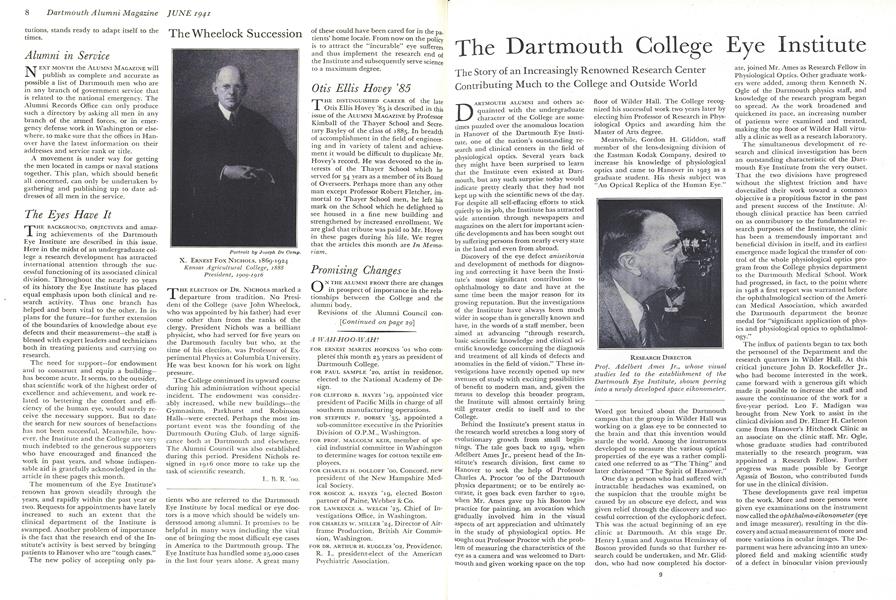

RESEARCH DIRECTOR Prof. Adelbert Ames Jr., whose visualstudies led to the establishment of theDartmouth Eye Institute, shown peeringinto a newly developed space eikonometer.

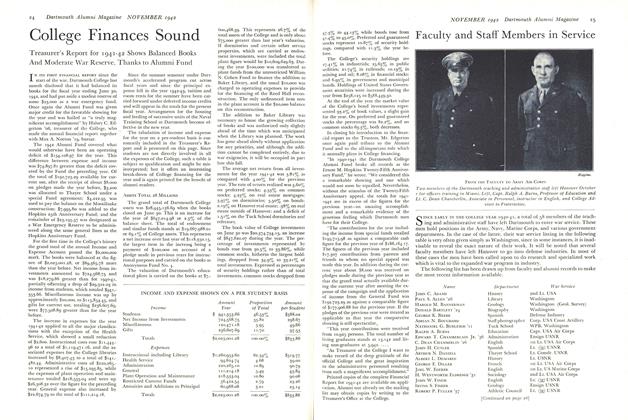

EXAMINATION SCENE AT THE EYE CLINIC Dr. Hermann M. Burian, a leading member of the staff of ophthalmologists, examines aDartmouth undergraduate with a binocular microscope, which with slit illuminationallows one to study the anterior part of the eye.

EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR John Pearson 'n, former U. S. Social Security official, who is administrative headof the Eye Institute.

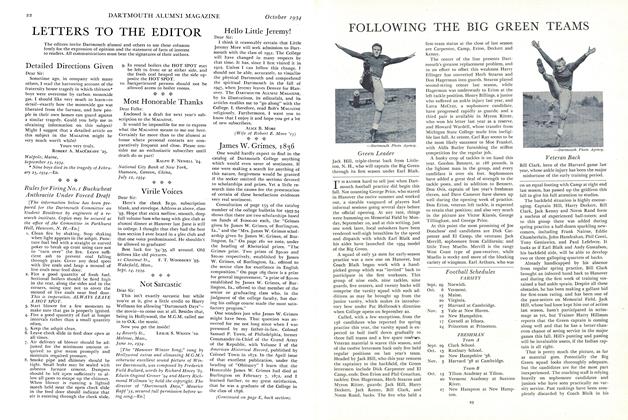

THE DARTMOUTH EYE INSTITUTE "FAMILY" Assembled for a staff picture at the request of the ALUMNI MAGAZINE are, left to right: First Row—Leo F. Madigan, Prof. Gordon H. Gliddon, Dr. Walter B. Lancaster, Prof. Adelbert Ames Jr., John Peanon 'll, Dr. Elmer H. Carleton '97 m. Second Row—Wendell Triller, Dr. Hermann M. Burian, Dr. Henry A. Imus, Prof. Kenneth N. Ogle, Dr. Arthur Linksz, I sabe!le Andruss, Robert E. Bannon, Camilla Hubscher, Rudolph T. Textor. Third Row—Prof. Irving E. Bender, Milton R. Thorburn, Ruth Humble, Helen Heartz, Leon E. Straw, Donald W. McKechney, Ellen Shattuck. Back Row—Barbara Jordan, Arlene Jenney, Mary England. Marv Beebe, Isabel Dickinson, Barbara Holden, Rosamond Scott, Norma Desßoches.

CLINICAL DIVISION OF THE INSTITUTEThe white frame building at 4 Webster Avenue, where patients from all over the countryare examined and treated for eye defects.

DR. HENRY A. IMUS AND PROF. GORDON H. GLIDDON OF THE RESEARCH STAFF (LEFT) USE AN OPTICAL INSTRUMENT FOR MEASURING THE CORNEA. AT THE RIGHT, DR. ELMER H. CARLETON OF THE CLINIC STAFF EXAMINES AN UNDERGRADUATE

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleA Versatile Engineer

June 1941 By Edwin A. Bayley '85, William P. Kimball '28 -

Sports

SportsBig Green Teams

June 1941 By Whitley Fuller '37 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1921*

June 1941 By CHARLES A. STICKNEY JR., ORTON H. HICKS -

Class Notes

Class Notes1929*

June 1941 By F. WILLIAM ANDRES, VAN NESS JAMIESON -

Class Notes

Class Notes1917*

June 1941 By EUGENE D. TOWLER, ARTHUR P. MACINTYRE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1940*

June 1941 By THOMAS W. BRADEN JR., ERNEST R. BREECH JR.

C. E. Widmayer '30

-

Sports

SportsBasketball

February 1934 By C. E. Widmayer '30 -

Sports

SportsGREEN SWEEPS SERIES

March 1934 By C. E. Widmayer '30 -

Sports

SportsGREEN DEFENSE HOLDS

March 1934 By C. E. Widmayer '30 -

Sports

SportsFRESHMAN NUMERALS

May 1934 By C. E. Widmayer '30 -

Sports

SportsFOLLOWING THE BIG GREEN TEAMS

October 1934 By C. E. Widmayer '30 -

Sports

SportsYALE OUTPLAYS INDIANS

December 1934 By C. E. Widmayer '30