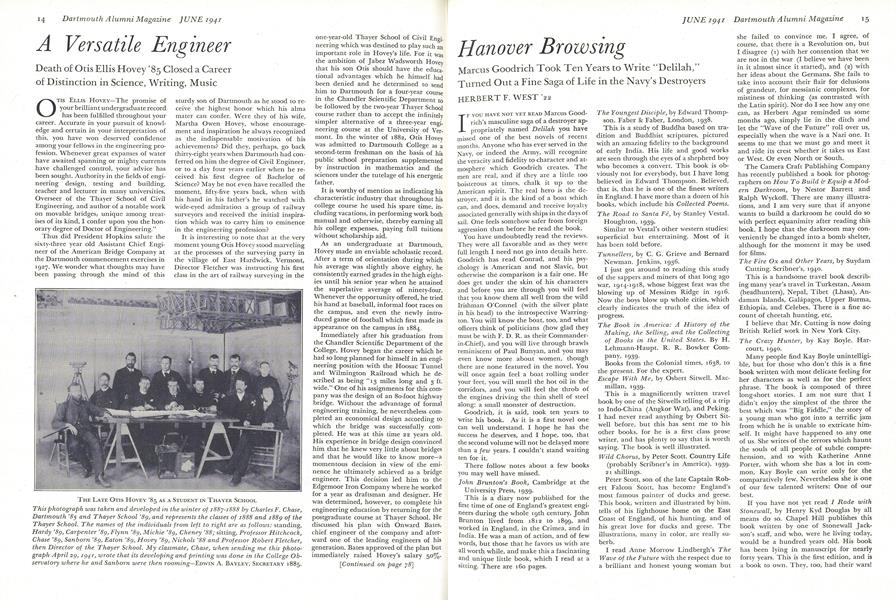

Death of Otis Ellis Hovey 'B5 Closed a Career of Distinction in Science, Writing, Music

OTIS ELLIS HOVEY—The promise of your brilliant undergraduate record has been fulfilled throughout your career. Accurate in your pursuit of knowledge and certain in your interpretation of this, you have won deserved confidence among your fellows in the engineering profession. Whenever great expanses of water have awaited spanning or mighty currents have challenged control, your advice has been sought. Authority in the fields of engineering design, testing and building, teacher and lecturer in many universities, Overseer of the Thayer School of Civil Engineering, and author of a notable work on movable bridges,- unique among treatises of its kind, I confer upon you the honorary degree of Doctor of Engineering."

Thus did President Hopkins salute the sixty-three year old Assistant Chief Engineer of the American Bridge Company at the Dartmouth commencement exercises in 1927. We wonder what thoughts may have been passing through the mind of this sturdy son of Dartmouth as he stood to receive the highest honor which his alma mater can confer. Were they of his wife, Martha Owen Hovey, whose encouragement and inspiration he always recognized as the indispensable motivation of his achievements? Did they, perhaps, go back thirty-eight years when Dartmouth had conferred on him the degree of Civil Engineer, or to a day four years earlier when he received his first degree of Bachelor of Science? May he not even have recalled the moment, fifty-five years back, when with his hand in his father's he watched with wide-eyed admiration a group of railway surveyors and received the initial inspiration which was to carry him to eminence in the engineering profession?

It is interesting lo note that at the very moment young Otis Hovey stood marveling at the processes of the surveying party in the village of East Hardwick, Vermont, Director Fletcher was instructing his first class in the art of railway surveying in the one-year-old Thayer School of Civil Engineering which was destined to play such an important role in Hovey's life. For it was the ambition of Jabez Wadsworth Hovey that his son Otis should have the educational advantages which he himself had been denied and he determined to send him to Dartmouth for a four-year course in the Chandler Scientific Department to be followed by the two-year Thayer School course rather than to accept the infinitely simpler alternative of a three-year engineering course at the University of Vermont. In the winter of 1883, Otis Hovey was admitted to Dartmouth College as a second-term freshman on the basis of his public school preparation supplemented by instruction in mathematics and the sciences under the tutelage of his energetic father.

It is worthy of mention as indicating his characteristic industry that throughout his college course he used his spare time, including vacations, in performing work both manual and otherwise, thereby earning all his college expenses, paying full tuitions without scholarship aid.

As an undergraduate at Dartmouth, Hovey made an enviable scholastic record. After a term of orientation during which his average was slightly above eighty, he consistently earned grades in the high eighties until his senior year when he attained the superlative average of ninety-four. Whenever the opportunity offered, he tried his hand at baseball, informal foot races on the campus, and even the newly introduced game of football which first made its appearance on the campus in 1884.

Immediately after his graduation from the Chandler Scientific Department of the College, Hovey began the career which he had so long planned for himself in an engineering position with the Hoosac Tunnel and Wilmington Railroad which he described as being "13 miles long and 3 ft. wide." One of his assignments for this company was the design of an 80-foot highway bridge. Without the advantage of formal engineering training, he nevertheless completed an economical design according to which the bridge was successfully completed. He was at this time 22 years old. His experience in bridge design convinced him that he knew very little about bridges and that he would like to know more—a momentous decision in view of the emi- nence he ultimately achieved as a bridge engineer. This decision led him to the Edgemoor Iron Company where he worked for a year as draftsman and designer. He was determined, however, to complete his engineering education by returning for the postgraduate course at Thayer School. He discussed his plan with Onward Bates, chief engineer of the company and afterward one of the leading engineers of his generation. Bates approved of the plan but immediately raised Hovey's salary 50%. Such encouragement and indication of immediate progress might have deflected a less steadfast 23-year-old from what might have seemed an unnecessarily rigorous path to glory through the discipline of the classroom. In fact, years later Bates admitted that the raise in salary was partly prompted by a desire to test Hovey's determination.

Resisting the temptation thus offered, Hovey returned to the Thayer School where for two years he led a class of eight students with averages of about 95. This record is particularly remarkable in view of the high academic standards maintained by Director Fletcher and his one-man faculty. Professor Hiram A. Hitchcock '79. But even the relatively short time required for the completion of the Thayer School course was not to be uninterrupted, for one day in February 1889 a call came from Washington University in St. Louis for an instructor in civil engineering. On Profes- sor Fletcher's recommendation, Hovey left Hanover that day for St. Louis.

The call of Washington University was the result of the illness of Professor J. B. Johnson, prominent educator and engineer whose monumental book on Materials of Construction remains to this day the outstanding textbook and reference on the subject. At the age of twenty-four, Hovey arrived in St. Louis to take over the testing laboratories of Professor Johnson and to continue Johnson's task of indexing periodical engineering literature for the As- sociated Engineering Societies. In addition the young instructor was required to teach a heavy schedule of classes in engineering subjects and chose, on top of this load, to continue his Thayer School course by mail which required the sending of reports, written examinations and graduating thesis. He maintained his 95 average in Thayer School courses, was graduated with his class in June, 1889, and has said of this period of his life merely that "This experience in teaching was most stimulating!"

In iBgo he entered the field which was to engage his principal attention for over forty years—bridge engineering. As engineer in charge of the Chicago office of George S. Morison, he accomplished several outstanding bridge designs before he reached the age of thirty. Perhaps the most important of these was the Bellefontaine Bridge across the Missouri River near St. Louis which was completed in 1893. Mr. Hovey described the influence of this association on his career as follows: "The years spent with Mr. Morison probably did more toward my development as an engineer than any other similar period; the contact was highly stimulating; the work was fascinating and there was plenty of it; everything had to be done the best we knew how and the best was never quite good enough."

There followed fifteen years of design and estimating work in many kinds of steel structures during which Hovey's prestige and responsibility increased in proportion to his accomplishments. During this period he made two trips to England and the continent in connection with proposed bridges and to investigate trade conditions. Two of the most interesting designs which he developed during this period may be mentioned. One of these was a pontoon bridge for the Golden Horn which was finally abandoned because of lack of funds for construction. The other was a 3200-foot suspension bridge across the Hudson River at New York City. At the time this latter design was prepared, the Brooklyn Bridge had been only recently completed and was considered an engineering marvel. No bridge had ever been constructed which approached the length required to span the Hudson River, and it is interesting to recall that no structure did span the Hudson River at New York until 40 years after Hovey prepared his design.

In 1907 he was named Assistant Chief Engineer of the American Bridge Company, a position he held until 1931. In this position, he was in responsible charge of some of the largest bridge projects which have ever been executed. He found some of the most fascinating and difficult problems in connection with the design and construction of movable bridges and, recognizing the lack of available information on the subject, proceeded to collect data and performance records and to develop the theory underlying the design of these complicated structures. For many years, he spent most of his spare hours in the preparation of a manuscript which was published in 1926 and 1927 in two volumes entitled "Movable Bridges." This treatise is still recognized as the most complete and authoritative work dealing with the subject and stands, as a matter of fact, in a class by itself. It was shortly after the publication of the treatise that Dartmouth awarded the degree of Doctor of Engineering to Hovey.

In 1931 Dr. Hovey was named consulting engineer for the American Bridge Company, and in 1934, at the age of 70, he retired to private practice as consulting engineer.

The Clarkson College of Technology honored Dr. Hovey in 1933 with the honorary degree of Doctor of Science, the presentation being made by the President of that college, Dr. John P. Brooks, who had been a classmate of Hovey's at Dartmouth in the Chandler Scientific Department.

During the first year of private practice, Dr. Hovey prepared a manuscript which was published in 1935 with the title "Steel Dams." At this time, too, he was continuing his active service for the American Society of Civil Engineers in the affairs of which he had been increasingly interested for many years. He held the position of Treasurer of this Society from 19a i until the time of his death giving to that office, according to Society officials, "a faithful, methodical and intelligent administration.

1937' at the age of 73 when most men are willing to let their activities taper off, he added to his consulting engineering work and to his duties with the engineering societies the responsibility of Director of the Engineering Foundation. It was appropriate indeed for Dr. Hovey to become the director of a foundation "for the furtherance of research in science and engineering or for the advancement in any other manner of the profession of engineering and the good of mankind," for this statement of the aims of the Engineering Foundation might equally well be applied to the life of Dr. Hovey himself.

Reviewing the career of Otis Hovey, one wonders how a man whose life was so full of scientific accomplishment and engineer- ing attainments could have found time for any activities outside of his profession. Yet he was one of the most loyal and energetic of Dartmouth alumni. His attendance at class reunions seemed as regular as if it were one of the laws of nature which as an engineer he had learned never to deny. For the last go years of his life he was a faithful agent of his class for the Alumni Fund, writing personal letters of appeal to each of his classmates. Coupled with his love of Dartmouth College was his devotion to the Thayer School which he served faithfully as a member of its Board of Overseers from 1907 until his death. His contact with the faculty and students of the School during these 34 years enriched their lives, for he was regarded by all as a model engineer to be emulated in character as well as in professional ideals and accomplishments.

Of these ideals he himself once wrote: "After having followed the professioji ofengineering for more than fifty years, oneis tempted to look back and try to assess thesatisfactions of such a career; a successfulengineer must possess and develop a hightype of character; he must be meticulouslyhonest with himself and others; he must beobedient to the laws of nature so far as hecan grasp them; he must be logical, thorough, industrious, inventive, practical, firmin well-grounded opinions, yet tolerant ofthe views of others and able to associatecomfortably with them; at the same time,he must see visions and dream dreams, andclearly visualize the embodiment of thedreams, whether in structures, machines,organizations, business, or human relationships While the financial rewards maynot be large the inner satisfactions aregreat. The engineer feels that he has at leastdone a little to advance civilization and theenjoyment of life by his friends and thepublic in general." How fully he embodied in himself all the requirements of his own high ideal! His life calls to mind the familiar lines

"Though deep, yet clear; though gentle,yet not dull;Strong without rage; without o'erflowing,full."

Dr. Hovey's real relaxation was found in music. He was himself an accomplished flutist and at one time vice president of the New York Flute Club. His appearance some years ago at a meeting of the can Society of Civil Engineers has been recalled in the annals of the Society in these words: "He assisted, with J. E. Greiner playing his Stradivarius violin and with Ralph Modjeski at the piano, in an evening of music which is still vividly remembered not only for its artistry but for the celebrity of the performers."

In 1937 Dr. Hovey received the highest honor which can be conferred on a member of his profession, Honorary membership in the American Society of Civil Engineers. The 15,000 members of the Society are representative of all parts of this country and many engineers from foreign countries seek membership. From this number the Society maintains an honorary membership of about twenty-five. In presenting Dr. Hovey for this high honor, Dr. John P. Brooks 'B5 has paid a tribute which must stand as our final words of one of Dartmouth's most distinguished alumni:

"He is a man born to wealth—to a wealth of character as sturdy as his native hills; to a wealth of ancestry that with others made our early history what it is; to wealth of family and local traditions honoring industry and honesty; to a wealth of appreciation of what is fine and beautiful in art and in nature; and to a wealth of mentality and ingenuity worthy of his pioneer forebears.

"Through the last decade it has been worth while to be in the rank and file of the host of earnest workers in science, research, and practice, all intent upon a common end—more efficient service.

"To be a leader in such an host is to have attained honorable distinction. Such a man I am presenting to you today. To me personally he is still, as he was a few yesterdays ago, a college classmate, but to you, Mr. President, I present the eminent engineer, Otis Ellis Hovey."

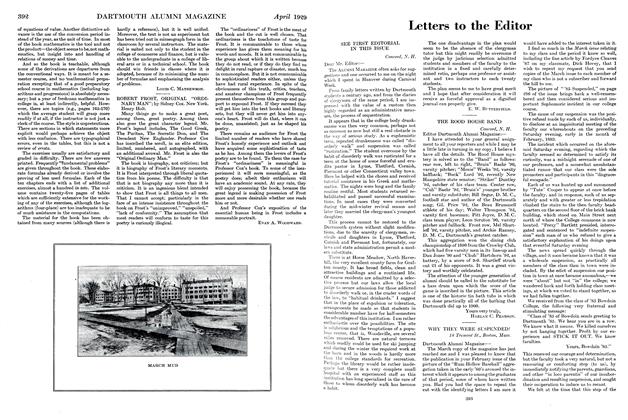

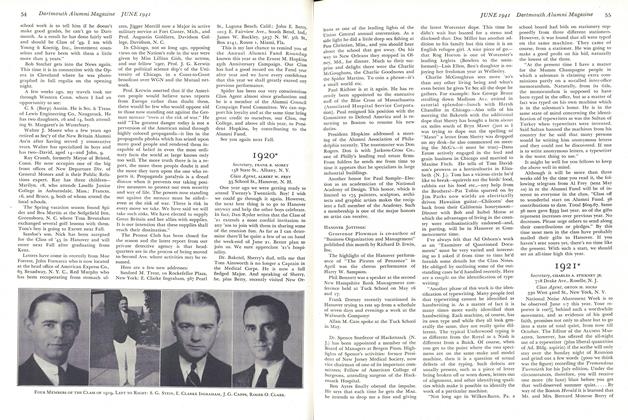

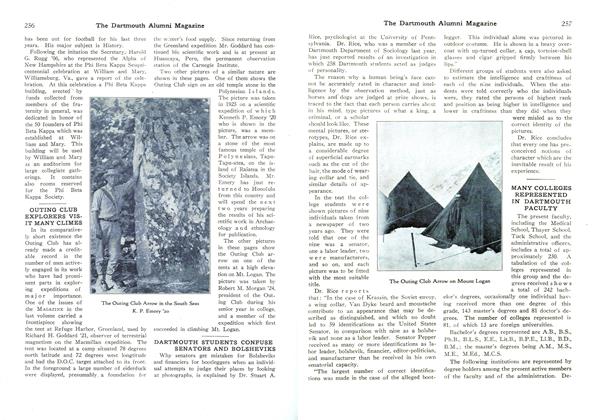

THE LATE OTIS HOVEY '85 AS A STUDENT IN THAYER SCHOOL This photograph was taken and developed in the winter of 1887-1888 by Charles F. Chase,Dartmouth '85 and Thayer School '89, and represents the classes of 1888 and 1889 of theThayer School. The names of the individuals from left to right are as follows: standing, Hardy '89, Carpenter '89, Flynn '89, Michie '89, Cheney '88; sitting, Professor Hitchcock,Chase '89, Sanborn '89, Eaton '89, Hovey '89, Nichols '88 and Professor Robert Fletcher,then Director of the Thayer School. My classmate, Chase, when sending me this photograph April 29,1941, wrote that its developing and printing was done in the College Observatory where he and Sanborn were then rooming—EDWlN A. BAYLEY, SECRETARY 1885.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleThe Dartmouth College Eye Institute

June 1941 By C. E. Widmayer '30 -

Sports

SportsBig Green Teams

June 1941 By Whitley Fuller '37 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1921*

June 1941 By CHARLES A. STICKNEY JR., ORTON H. HICKS -

Class Notes

Class Notes1929*

June 1941 By F. WILLIAM ANDRES, VAN NESS JAMIESON -

Class Notes

Class Notes1917*

June 1941 By EUGENE D. TOWLER, ARTHUR P. MACINTYRE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1940*

June 1941 By THOMAS W. BRADEN JR., ERNEST R. BREECH JR.

Edwin A. Bayley '85

William P. Kimball '28

-

Class Notes

Class NotesDartmouth in T. V. A

October 1936 By Davis Jackson '36, William P. Kimball '28 -

Class Notes

Class NotesThayer School News

April 1936 By William P. Kimball '28 -

Class Notes

Class NotesThayer School News

June 1936 By William P. Kimball '28 -

Article

ArticleThayer School News

November 1936 By William P. Kimball '28 -

Article

ArticleThayer School

February 1937 By William P. Kimball '28 -

Article

ArticleThayer School

January 1944 By William P. kIMBALL '28

Article

-

Article

ArticleIn describing the successful working

February, 1910 -

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH STUDENTS CONFUSE SENATORS AND BOLSHEVIKS

JANUARY, 1927 -

Article

ArticlePresident to Speak

April 1936 -

Article

ArticleSenior Graduate

June 1938 -

Article

ArticleAlumni Register

April 1951 -

Article

ArticleThe Irish and Other Problems

MAY 1982 By Frank C. Newman '38