Pictures Wanted

To THE EDITOR:

For a long time I have enjoyed my ALUMNI MAGAZINE and each month look forward eagerly for the next issue.

There is, however, one slight criticism that I should like to make and this is it. Some years back the MAGAZINE had many more pictures, it seems to me, of the Old Dartmouth, than the current numbers have. There were frequently pictures of old scenes, student groups, etc. taken well before my time and these were extremely interesting to me. Lately it seems that the pictures are more of recent people and present day views.

Might I make this suggestion? Why not give views and student groups of those classes having regular reunions coming up the following June? This has been done in a slight degree I know but not so much as I should like. For instance in this year's issues there would be piclures of scenes, athletic, and non-athletic groups of the classes of '37, '32, '27, '22, etc. back to the 50-year class. I feel sure that these pictures would be welcome to all ALUMNI MAGAZINE readers and furthermore would stimulate the interest for coming class reunions.

Rumford, Maine.

[Mr. Maynard's suggestion will be adoptedand old pictures of general interest will bepublished more frequently. The College filesare far from complete for all years. We wouldbe grateful for prints (and preferably negatives) that may be loaned to the ALUMNI MAGAZINE. Gifts of photographs and negatives willbe turned over to Baker Library for permanentpreservation— ED.]

"Good'' Not "Must"

To THE EDITOR:

Your list of good books irritates me. I am no literary expert but I probably own more books and have read more books than the average college man. There is no such thing as a list of must books any more than there is such a thing as a list of must women. "If she be not fair to me, what care I how fair she be?" By all means recommend The Bible, Webster'sDictionary (unabridged, second edition—Merriam), the Encyclopedia Brittanica in 24 volumes (which anyone can get by courtesy of Lucky Strike), any good poetry anthology, Bartlett's Quotations, the Dartmouth CollegeGeneral Catalog, and the World Almanac, even Shakespeare's plays and poems, but when it comes to putting other books on a must list, I'll take a plain soda.

You can have The Seiten Pillars of Wisdom, but give me Alice in Wonderland and Throughthe Looking-Glass; I'll swap South Wind and all of Norman Douglas for Treasure Island and all of Robert Louis Stevenson. The OldWives' Tale is a wonderful story (as are all of Bennett's) and so is Of Human Bondage, but what about Bernard Shaw, Oscar Wilde, Charles Dickens, Sinclair Lewis (he wrote three real books, anyway, Main Street, Babbitt, and Arrowsmith), Christopher Morley, Edna Ferber? Willa Cather may be a better writer than Theodore Dreiser, but I have a copy of A LostLady, which I will trade for An AmericanTragedy and I will throw in One of Ours. What excuse have you got for leaving out LesMiserables and The Scarlet Letter?

Don't you care for Gertrude Stein and James Joyce? Neither do I, but there are those who do, believe it or not. I am nuts about Wodehouse, although I don't think there is much point in buying his stories, as after you have read them, what can you do but lend them to someone, who probably will say "what is funny about Jeeves?" Harry Leon Wilson, whom you ignore, has written some great stories; and so has Elmer Davis. If a man doesn't know what books to read or to buy without joining the Book of the Month Club or asking Carl van Doren or Alexander Woollcott or Clifton Fadiman or Lewis Gannett or Herb West, he probably doesn't know how to read anyway and if he bought the books you suggest, he would continue to read the Saturday Evening Post and Life.

As for history, biography, science, and other non-fiction, it is even more difficult to say what is good. I prefer to read the Autobiography ofCalvin Coolidge rather than The Educationof Henry Adams. But I know that HenryAdams is a more important book. All biography is interesting more because of its subject than because of its literary style. As to history, although I have many books of an historical nature, in general my reaction to a history book is "even if it was good, I wouldn't like it." In this field, however, I believe advice may well be sought. If I were expecting to be cast away on a desert island, I think I should want ten books on history, because they would last me longer.

Pay no attention to this letter. It is not intended to be taken seriously. After you have read it (if you read it) tear it up and file it in the wastebasket, the "Don't Give It Another Thought Department." As Bunker Bean said (Do you know Bunker Bean?) "I can think of nothing of less consequence." But the next time you are tempted to publish a list of good books, don't say all of them belong on any Dartmouth Book Shelf, or that they are must books.

Brattleboro, Vt.

["Ich" Crane is one of the best friends of theDartmouth Alumni Magazine and its exceed-ingly able printer, since 1928. His comments(left) on the "Hanover Browsing" suggestionsof last month were addressed to Prof. HerbertF. West and kindly given to the editor for publication.— ED.]

Military Service

To THE EDITOR:

Will you please give me any information you have available regarding the possibilities for getting a commission in some branch of the Service? Here is the story:

I was classified IB—fit for limited serviceby my draft board about a year ago, because of nearsightedness-not an acute case however. At that time this automatically disqualified me from the Air Corps, VB, and the other popular branches of the active service. Have these physical qualifications been relaxed? If not, is there any branch for which the eye sight test is more lenient, such as the Intelligence Service or Meteorology Service? What are the prerequisites for some of these specialized services? Have any 1B men been accepted or drafted and if so, what type of work have they been doing?

If my letter should have been directed to someone else, will you please pass it On to the proper party. Thanks for your help.

Nashua, N. H.

[ED. NOTE: Prof. Donald L. Stone, chairmanof the military service committee of the Defense Group, has edited the Dartmouth College Defense Bulletin No. 3 giving full details ofrequirements for all branches of the service.Copies may be secured by writing the defenseoffice in Hanover, 230 Baker Library. The ALUMNI MAGAZINE hopes to publish, in anearly issue, revised conditions of both voluntary and Selective Service requirements. Mr.Stone's reply to specific questions raised aboveby Mr. Lyle follows:

"The Army and the Navy have standardphysical examinations that are given to almost all candidates for specialized reserve commissions. They are not severe, merely requirenormal health and possession of physical faculties. The Army eye requirements for reservecommission are: (I) minimum vision of 20/100in each eye, correctible with glasses to 20/20 inone eye and 20/30 in the other eye; (2) noorganic disease in either eye; (3) no pronounced impairment of color perception; ability to distinguish red and green. Naval reserveofficer: (1) vision of 20/20 unaided; (2) no orgranic disturbance; (}) standard color perception. (Supply corps: vision 15/20 unaided, corrected to 20/20 by proper glasses.)

"In a very few cases where keen sight andhearing are obviously required, as in pilotaviation, the standards are higher. Occasionally, as in case of research chemists, regulationsstate that reasonable allowance will be madefor vision defects.

"In branches requiring unusually good vision, I think we may reasonably expect no lowering of physical requirements. There will almost surely be some modification downwardin the case of men commissioned for office orlaboratory work, when they are actively neededor desired.

"No '18' men have been called under Selective Service yet. Personally, I doubt whetherthey will be in any immediate future. For onething, the declaration of war has brought aflood of enlistments that will slow down alldrafts calls for the time being. For another,new registrations will put into the 'live file' somany 'IA' men that there will be no great rushto re-examine or call for limited service the'18' men. At least, that's the way it looks-."]

Correction

To THE EDITOR:

Will you let me correct a mistake in this column in your last issue, for which I am mainly responsible? In the letter which my classmate, Paul Jenks, wrote about the Flushing High School award, the statement was made that the man who received the award last year, Timothy Takaro, was the salutatorian of the class of '41. As a matter of fact, he was the valedictorian and ought to have his full credit. My apologies are to him. However, I might say that the impeccable NewYork Times was the first to make the mistake.

Boston.

Secretary, Class of '94.

Daniel Webster Day

To THE EDITOR:

A Daniel Webster Memorial Service commemorating Webster's 160 th birthday anniversary, will be held Sunday, January 18, at 11:00 A.M. in the Federated Church, Old Sandwich Village, on Cape Cod. The service will be conducted by Rev. Alexander L. Chandler, B. U. '30, the church pastor and the informal orator of the day, and Lt. Col. Raymond Lang '17, senior chaplain at Camp Edwards.

At 1:00 P.M. a steak dinner will be served at the centuries old Daniel Webster Hall, D. W.s favorite rendezvous in his later days. At this time a full length statue of America's Number 1 statesman and Dartmouth's most famous graduate will be brought to light.

Taps will be played in Marshfield at 4:37 P.M. and a wreath of laurel from "Men of Dartmouth" will be placed on Webster's grave where he was buried 90 years ago. For dinner reservations (limited to 100, at $1.00 per for enlisted men and $1.50 for other alumni) please write or phone your name and class to me at the Daniel Webster Inn, Sandwich, Massachusetts, Sagamore 590.

Sandwich, Mass.

Is It Art?

To THE EDITOR:

According to Rudyard Kipling, this disturbing question was originated by the Devil, who whispered it between the leaves in the ear of our father Adam, just as that worthy was completing the first rude sketch ever made by man. The obvious implication is that anything pretty must be suspect; and only less obvious is the hint that if a thing is ugly a presumption arises that it must be artistic.

Perhaps that is only fair. Ugliness merits some compensation, even if it be no more than a suggestion that it may be Art though lacking in the superficial attributes of beauty. What we should guard against, no doubt, is the rash assumption that beauty is never Art and that ugliness always is, merely because the one is obviously pretty and the other superficially repulsive—or, if not repulsive, at least what one may charitably describe as "plain."

Beyond question there is beauty in the bellow of the blast and grandeur in the growling of the gale, as Gilbert so pertinently suggests; but it is the beauty of impressiveness and depends mainly on the dynamic. To the eye of love, such as that with which an engineer views his material constructions, there is something beautiful in a pylon for sustaining aloft a string of high-tension wires. Even a layman may be so impressed by the power of a Pacific type locomotive that it will strike him as unspeakably beautiful, even though it makes no attempt to appeal on the score of aesthetic charm. To most of us, a clipper ship under full sail has a beauty wholly lacking in a lop-sided airplane-carrier of the modern navy; but this may not wholly disprove the right of the airplane carrier to assert that it has a beauty of its own.

One man's meat is traditionally another man's poison—a rather merciful provision of Nature. "Otherwise everybody'd want my John," as one lady once observed. Gargantua and Toto presumably have standards of pulchritude, very different from those by which we estimate the beauties of the Hermes of Praxiteles and the Venus of Melos, but for them they are no doubt valid criteria. It is when we differ among ourselves concerning the works of Art devised by human beings that the greatest difficulties arise; and the Roman observation still holds good that it is futile to dispute concerning matters of taste.

These random thoughts are suggested by the conflict of opinion which has surged about the mural paintings in the basement of the Baker Library ever since Senor Orozco spread them there. One may admit at once that these decorations differ radically in their appeal from the frescoes with which Michaelangelo adorned the vaulted ceiling of the Sistine. They have nothing in common with the Rafaelle stanze, or the famous chambers of the

Vatican decked with the murals from the brush of Pinturicchio. The artist who produced them is an accomplished modern painter, who could paint in the most modern mode if he chose—but he did not choose. The question here suggested concerns the validity of the choice.

"WHY NOT?"

That choice appears to be a deliberate election to revert to the primitive style as a dominant key—rather a sophisticated primitive, to be sure, but certainly not the sophistication of a Sargent or an Abbey. The result is better than could have been achieved by an Aztec or Mayan artist with a smaller knowledge of perspective and a ruder sense of color values; but the effect sought is obviously that of the dawn of artistic time in Central America and it would be rash to condemn the choice as inappropriate. Senor Orozco had as his theme a primitive view of religion and culture; and as the medium for expounding it he has spread on the walls of our Dartmouth College Library a series of frescoes suggestive of the manner in which this would have been done many centuries ago when men didn't know so much about pictorial art as they do now. To those who ask why, it is quite plausible to retort, "Why not?" If this thing must be done at all, doubtless this is the way to do it.

There is an argument to be made, based on the feeling that there is some derogation from artistic standards when a painter who knows more elects to paint in the idiom of one who knows less. It has to be remembered that the primitive artists, whose general style Senor Orozco adopts in these mural decorations, were doing the best they knew how to do and were striving to be realistic. So, it is to be presumed, were the much earlier Egyptian painters who depicted heads in profile only to insert eyes seen full-face. Is there virtue, then, in aping this method, in an age which has advanced to a greater skill in reproducing the natural?

To one school of thought it seems as indefensible for a skilled modern artist to play at being caveman as it would be for John Singer Sargent to recall the rude scrawls of the schoolboy—those rude scrawls being the very best a schoolboy can do in his effort to portray the thing as he sees it for the God of Things as They Are. Senor Orozco isn't doing that. He is depicting the things as an Aztec (or other primitive Central American) painter thought he saw them—for whatever Gods There Be. The difference is that the ancient artist was doing his level best to be realistic about it, and Senor Orozco isn't. The latter knows perfectly well that he isn't being realistic; the former didn't even suspect it, and the same was true of his contemporary beholders.

When the great painters of the Italian Renaissance were adorning the aisles of Christian Rome they seldom reverted to the fiat paintings of the Byzantine artists, or the Sienese who flourished in the pre-Giotto period. They were too thoroughly enchanted by the new-found power to reproduce three-dimensional objects on a flat canvas. Primitive painting was old hat. It was the sort of thing men did when men didn't know any better. Giotto had pointed the way to more realistic art, and Masaccio had blazed the trail which the great muralists of the cinquecento converted into a broad highway. It isn't quite the same now. A nostalgic yearning for the old simplicities appears to have set in; and for the question whispered by Satan in the ear of our father Adam there is substituted another, antithetical question: "It's ugly—but isn't it Art?"

TEACHES UNWELCOME LESSON

Recurring to the Orozco murals in the Baker Library, it seems to the present writer that there is less question of the artistry than of the appropriateness of both place and subject. Is the basement of an American college library the fitting site for a series of paintings in primitive style, in which the dominant motif is the suggestion that our boasted modern civilization is a sordid sham and that our vaunted higher education leads only to dust and ashes? We have substituted something less bloody for the aboriginal American's human sacrifice, but in the present state of the world there may be room for question as to the net benefit conferred. Perhaps Senor Orozco painted better than he knew; and quite possibly it is well for us to be flicked on the raw.

We may disregard for the moment alike those who honestly admire the Orozco frescoes and those whose admiration is a pretentious pose. The real question is for those who come to scoff—whether or not they shall remain to pray. The element of artistry also we may disregard, for the overwhelming majority seems to be in agreement that at least the Orozco paintings are, in their deliberately crude way, decorative; and that, one may assume, is their real raison d'etre. It isn't pretty but isn't it Art? What one may well deplore is the propensity to quarrel over the purely artistic aspects of the case and to ignore the unwelcome lesson which it seems the painter intends to teach; to wit, the shortcomings of our cultural attainment, of which we are so proud. It is a rude lesson, driven home by rude means—but it may be it was, in the expressive vernacular speech, "coming to us," for our sins. If it be true, it isn't an insult. If it be painful, it may be a useful and muchneeded spur. Have we substituted for the prophets of Quetzalcoatl the worship of Jehovah, or the worship of Mammon? The artist may seem to be thumbing his nose at modern civilization, modern education and modern (or Victorian) art; but if he is in appreciable measure right, he may not have painted in vain.

Lowell, Mass.

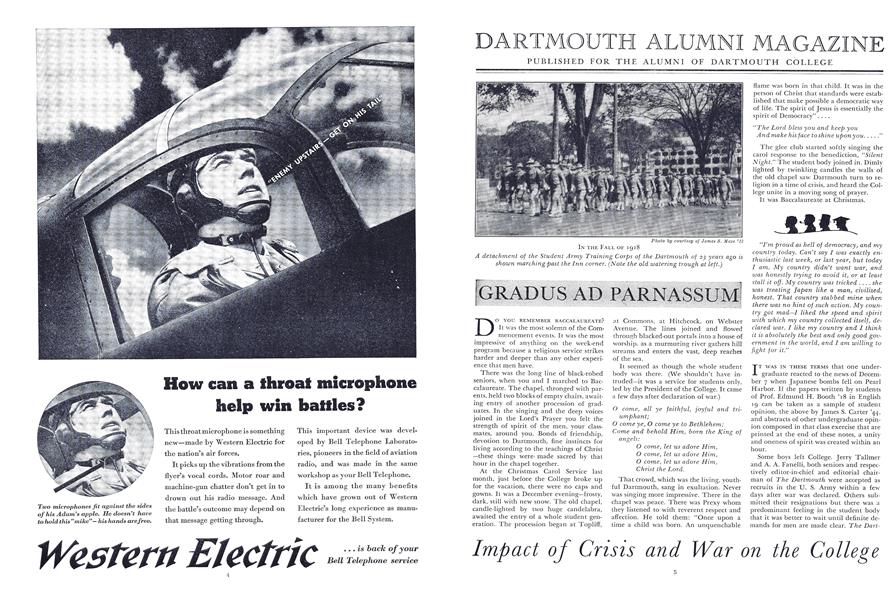

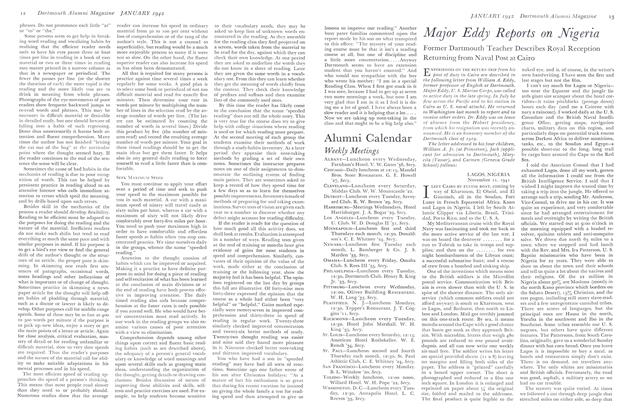

INSTRUCTION IN WAR INDUSTRY Fred F. Parker 'O6 (left), professor of graphics, supervises his evening course in Engineering Drawing, in connection with the national training program. The course, not open tostudents, has an enrollment of 43. It has been planned to assist employees to qualify forpositions of greater responsibility in defense industries. The group shown above is drawnfrom Hanover and nearby industrial centers.

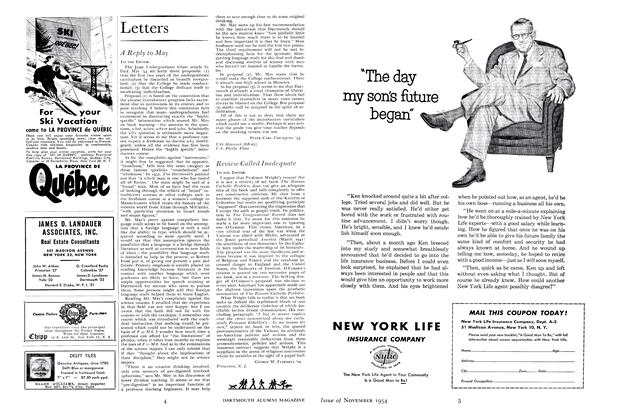

NEW INSTRUCTOR IN THE DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH Walter E. Bezanson '55 joined staff of the English Department this fall after studying atYale. He held the Richard Crawford Campbell Jr. Fellowship from Dartmouth in 1937-38.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class Notes1936*

January 1942 By EDWARD T. CHAMBERLAIN JR. -

Article

ArticleSpeeded Reading

January 1942 By ROBERT M. BEAR asst. -

Article

ArticleWar Measures Adopted

January 1942 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

January 1942 By Craig Kuhn '42. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1911*

January 1942 By PROF. NATHANIEL G. BURLEIGH -

Class Notes

Class Notes1937*

January 1942 By DONALD C. MCKINLAY