Special Group Work Is Designed to Aid Students in Comprehension and Rate of Silent Reading

SPEEDED READING"—such is the campus sobriquet for what the college catalog describes in carefully measured terms as:

Techniques of Silent Reading and Study

Since reading is so important in a student's work, this course is designed to offer opportunity for practice to increase speed of reading and improve comprehension. Analysis is made of the individual's skills and abilities through diagnostic tests, stereoscopic slides for vision, eye movement photographs and inventories, accompanied by appropriate training. Demonstration of procedures is given through motion picture and projection lantern exercises, with training in techniques useful for better reading of regular course assignments. The Dartmouth Eye Institute will be glad to cooperate in the analysis of cases of ocular disability. Offered each half semester through the year. Non-credit.

When in 1935, Dartmouth decided to make a reading improvement service available generally to students, it was one of less than a dozen institutions which could trace some provision in this line back to the late twenties. But the novel feature in college circles of the new plan was to attempt an offering of such wide usefulness and appeal that it would be helpful, if possible, both to better and poorer readers; that though especially intended for freshmen it would also meet the needs of upperclassmen. Although it was arranged to bring possibilities of the work to the attention of the poorer readers, participation on the part of any student was to be voluntary and without academic credit.

Another unusual feature was the condensation of the work of a group into about twelve periods, with meetings twice a week for half a semester. Elsewhere such instruction ran the full semester or quarter, but with the high type of student coming to Dartmouth it appeared that we could safely experiment with a plan which called for less minute and prolonged class instruction. It seemed a reasonable assumption that we could rely to a fair degree upon many students exercising intelligence in studying their own needs and difficulties through transferring what was learned in the reading group to their own courses. On the other hand, supplementary individual help and instruction was to be given to those wishing it or whose needs seemed to indicate its desirability.

Such was and continues to be our charter. Men are given opportunity to participate through notices in The Dartmouth, personal inquiry, at the suggestion of an instructor, or through passing in their names in freshman English sections where explanatory announcement is made each fall. The scores made by freshmen on the entering reading test are examined to discover which are relatively the poorer readers. Some of these are called together, the course explained and work begun for those wishing to try to improve their reading. Also whenever marks are reported by instructors, the records of freshmen are examined to learn whether the trouble men may be having in courses involving considerable reading, might be due to reading difficulty. Such students are notified of a reading group meeting at an hour suited to their schedules.

Through these various contacts about 200 men each year participate in the work, taking both initial and final tests and being present on an average of 10 periods if with a group, or for shorter or longer time if having individual instruction.

Perhaps the reader of this account is wondering why it should be desirable, much less necessary, for a college to offer any instruction in reading. A number of replies might be made to such a question. For one thing, this is merely another reflection of the concern for the individual from the personnel standpoint so general throughout both business and educational organizations today. Another factor is the wide reading required by contemporary college curricula. The modern college library presents a challenge to any instructor to supplement or replace by extensive reading the familiar one-text requirement. Both the nature of many of the problems studied and the amount of data needed for their attack have changed, so that wider coverage of materials is necessary as well as particular reading abilities formerly not so important.

For some years the difficulty of the transition from secondary school to college has been recognized. Part of this difficulty is due to the fact that the level of development of reading skills and study habits satisfactory for successful work in the secondary school is not always adequate for college work. And perhaps equally important is the fact that the student often does not realize this until sad experience brings it home to him. For example, last year over 200 freshmen were asked in reading groups to estimate how satisfactory was the size of their vocabulary. Of those actually in the lowest fifth of the freshman class in vocabulary on the entering test in September, only 13.5 per cent checked "very limited" while 45 per cent checked "average." Vocabulary is an important factor in success in college course work and one of the first jobs of a reading program is to help the student correct the error in his self-appraisal and take steps to make the necessary improvement. These particular students were slightly better judges of their speed since of the slowest fifth on the September test, 19.7 per cent characterized themselves as"very slow" readers and only 29.6 per cent as "average."

A question is often asked about the types of ineffective reading found in a selective student group such as at Dartmouth. One of the more infrequent difficulties yet always present in a few, is in word recognition. That is, the person experiences confusion between words of similar appearance, or with similar beginnings or endings. He cannot tell without a second glance, for example, whether the word before him is through or though, angle or angel, weather or whether. Others seem to conceive of reading as a process of examining each word and memorizing what has been read. With them, reading is likely to be a very slow and mechanical process although a few mechanical readers go to the opposite superficial extreme and attain the dizzy pace of a ladder wagon going to a four-alarm fire. Other plodding readers are far from mechanical and make it a very thoughtful process. With all readers at times and with some much of the time there is poor attention to the thought, a situation calling for finesse as well as selfdiscipline. Others re-read every few words, merely from force of a habit of constantly checking up on themselves, much as Caspar Milquetoast might do. One of the more common failures in connection with course assignments is purposeless reading. Many students seem unskilled in getting before them the purposes which the given assignment serves and thus make ineffective connections between their reading and the problem or topic being studied. There are some with underdeveloped stocks of meanings and concepts—the necessary ideational background for interpreting material. A few have never as yet found reading an interesting way of getting experience and so are indifferent or dislike it. Many read more slowly than they need to for the attainment of maximum pleasure from the process.

Without further extending this list of deficiencies we may classify them under four main types:

1 .Lack of experience and background. The strategic place for giving what is lacking is in the course where the deficiency becomes apparent. If special ways of thinking, knowledge or vocabulary are necessary for reading in a subject, they can best be acquired by measures taken by its instructor.

2. Purposeless reading. The purposes a reader should have vary from one assignment to another, from one course to another. Since purposes are specific to specific pieces of subject matter, students can best be helped to develop purposeful attitudes through the way course assignments are made and the course conducted.

3. Lack of interest in learning throughreading, or more simply, few reading interests. It is usually assumed that these should grow out of the subjects studied and the ways they are taught. Some of the lower schools have thrown up the sponge with some of their pupils and no longer try to develop interest in learning through reading but try instead to help them learn in other ways. If the lack of interest is due to difficulty the pupil has with the reading process, it is clear that this should be remedied before subject-matter instructors can be expected to have much success in stimulating interest in reading.

4. Deficient basic reading and study skills. Although valuable aid comes from instructors, a direct attack through special instruction is particularly helpful, and this is the area on which Dartmouth "speeded reading" especially focuses.

Some of these basic reading needs and difficulties, and ways we have tried to meet them, might be of interest since they also concern adults.

Mechanically, reading is a process in which through pauses of the eyes at intervals along a line of print, words are seen which awaken meanings and ideas in the brain. Two misconceptions of this process are common. One is that it is necessary to be conscious of every individual word. Unless the words are largely unfamiliar, the thought very difficult for the reader or he desires to study the choice of words used by the author, he should not strive to be conscious of each word. Too great attention to individual words hinders the getting of several together in the mind at one time—something which is necessary if the author's thought is to be interpreted correctly. In the same way a dirty window pane through distracting attention to itself blurs the clearness of the scene without. If one reads under 175 words per minute in ordinary material he almost certainly is a word reader. Effort to increase your speed and keeping in mind that what you are trying to get are ideas, not words, will help break this habit.

The other common misconception is that it is necessary to pronounce words to yourself to get the meaning. This habit of vocalizing developed in most of us because as children we were taught to read by oral methods and have never dropped the practice. It isn't really necessary and has disadvantages such as a sharply limited rate. Fastening attention on getting ideas, forcing a faster rate and keeping the vocal cords and tongue as still as possible will in the end break the habit and improve reading greatly. If you feel you must pronounce, then restrict it to the important words of phrases. Do not pronounce each little "at" or "to" or "the."

Some persons seem to get help in breaking word reading and vocalizing habits by realizing that the efficient reader needs only to have his eyes pause three or four times per line in reading in a book of easy material or two or three times in reading easy matter printed in a narrow column as that in a newspaper or periodical. The fewer the pauses per line (or the shorter the duration of each) the more rapid is the reading and the more likely you are to drink in meaning from whole phrases. Photographs of the eye-movements of poor readers show frequent backward jumps to re-read words and phrases. This may be necessary in difficult material or desirable in detailed study, but one should beware of falling into a habit of such regressing. Done thus unnecessarily it harms both attention and fluent comprehension. Many times the author has not finished "letting the cat out of the bag" at the particular point where the thought seemed hazy. If the reader continues to the end of the sentence the sense will be clear.

Sometimes the cause of bad habits in the mechanics of reading is due to poor recognition of words. This can be helped by persistent practice in reading aloud to an attentive listener who calls immediate attention to errors which spoil the meaning, and by drills based upon such errors.

Besides skill in the mechanics of the process a reader should develop flexibility. Reading to be efficient must be adapted to the purposes for doing the reading and the nature of the material. Inefficient readers do not make such shifts but tend to read everything at much the same pace and with similar purposes in mind. If his purpose is to get a bird's eye view or find the general drift of the author's thought or the structure of an article, the proper pace is skimming. In skimming one reads first sentences of paragraphs, occasional words, notes headings and other indications of what is important or of change of thought. Sometimes practice in skimming a newspaper article for the thought will help offset habits of plodding through material, such as a doctor or lawyer is likely to develop. Other purposes call for middle range speeds. Some of these may be as fast as 400 to 500 words per minute if the purpose is to pick up new ideas, enjoy a story or get the main points of a letter or article. Again for close analysis, critical evaluation, mastery of detail or for reading unfamiliar or difficult material, slow to very slow speeds are required. Thus the reader's purposes and the nature of the material call for ability to make suitable adaptations in his mental processes and in his speed.

The most efficient speed of reading approaches the speed of a person's thinking. This means that most people read slower than they need to or probably should. Numerous studies show that the average reader can increase his speed in ordinary material from go to 100 per cent without loss of comprehension or of the tang of the author's style. This is not a counsel to superficiality, but reading would be a much more enjoyable process to many if it were not so slow. On the other hand, the fluent superior reader can also increase his speed as has often been demonstrated.

All that is required for many persons is practice against time several times a week regularly for some weeks. A good plan is to select some book or periodical of not too difficult material and read for exactly five minutes. Then determine your rate in words per minute by multiplying the number of lines in the selection read by the average number of words per line. (The latter can be estimated by counting the number of words in several lines.) Divide this product by five (the number of minutes read) and record the resulting average number of words per minute. Your goal in these timed readings should be to get the main ideas but get them faster. It helps also in any general daily reading to force yourself to read a little faster than is comfortable.

SEEK MAXIMUM SPEED

You must continue to apply your effort over a period of time and seek to push your speed to the maximum possible for you in such material. A car with a maximum speed of ninety will travel easily at sixty miles per hour, whereas a car with a maximum of sixty will not likely drive comfortably over forty-five miles per hour. You need to push your maximum high in order to have comfortable and effortless faster speeds as habits when you stop concentrated practice. We time ourselves daily in the groups, whence the name "speeded reading."

Attention to the thought consists of habits which can be improved or acquired. Making it a practice to have definite purposes in mind for doing a piece of reading and self-recitation of what has been learned at the conclusion of main divisions or at the end of reading have both proven effective in improving attention. The daily timed reading also aids because comprehension at the faster rates is only possible if you attend well. He who would have better concentration must read actively. In our work in the reading groups we also examine various causes of poor attention with a view to elimination.

Comprehension depends among other things upon correct and fluent basic reading habits (such as are described above), the adequacy of a person's general vocabulary or knowledge of word meanings and upon several skills such as grasping main ideas, understanding the organization of the thought, getting details or drawing conclusions. Besides discussion of means of improving these abilities and skills, selftests and practice exercises are used. For example, to help students become sensitive to their vocabulary needs, they may be asked to keep lists of unknown words encountered in the reading. As they assemble for the reading class they find projected on a screen, words taken from the material to be read for the day, against which they can check their own knowledge. At one period they are asked to underline the words they do not know in a sheet of reading. Later they are given the same words in a vocabulary test. From this they can learn whether they get the meaning of words chiefly from the context. They check their knowledge of prefixes and suffixes and then examine lists of the commonly used ones.

By this time the reader has likely come to the conclusion that the name "speeded reading" does not tell the whole story. This is very true for the course does try to give help with college situations where reading is used or for which reading must prepare. At the second meeting of each group the students examine their methods of work through a study-habits inventory. At a later period they appraise their note-taking methods by grading a set of their own notes. Sometimes the instructor prepares notes on one of their assignments to demonstrate the outlining system of finding main points. They are sometimes asked to keep a record of how they spend time for a few days so as to learn for themselves possible impro vemen ts. Inven tory is made of methods of preparing for and taking examinations. Survey tests of vision are given each year to a number to discover whether any defect might account for reading difficulty.

If the reader is ready for the question of how much good all this activity does, we shall look at results. Evaluation is attempted in a number of ways. Reading tests given at the end of training or months later give evidence of gains for most students in speed and comprehension. Similarly, canvasses of their opinion of the value of the work, made either at the conclusion of training or the following year, show the majority feel it has been helpful. The opinions registered on the last day by groups this fall are illustrative. Of forty-nine men forty-three expressed the opinion that the course as a whole had either been "very helpful" or "helpful." Gains marked especially were twenty-seven in improved comprehension and thirty-three in speed of reading in regular work. Twenty-three similarly checked improved concentration and twenty-six better methods of study. Twenty-two thought reading was easier and nine said they found more pleasure in it. Nineteen checked better note-taking and thirteen improved vocabulary.

You who have had a son in "speeded reading" may have had all sorts of reactions. Sometime ago one father wrote of his son after Christmas holidays: "As a matter of fact his enthusiasm is so great that during his recent vacation he insisted on giving the whole family a test for reading speed and then attempted to give us lessons to improve our reading." Another busy pater familias commented upon the report made by his son on what transpired to this effect: "The mystery of your reading course must be that it isn't a reading course at all, but one of discipline and a little more concentration Anyway Dartmouth seems to have an extension student that you haven't counted." And who would not sympathize with the boy who wrote his mother: "I am in a special Reading Class. When I first got stuck in it I was sore, because I had to get up at seven two more mornings a week, but now I am very glad that I am in it as I feel it is doing me a lot of good. I have always been a slow reader and it is helping that a lot Now we are taking up note-taking in the class and that ought to be a big help also."

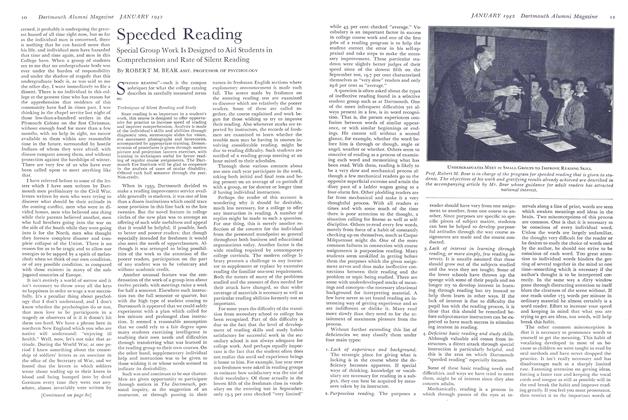

UNDERGRADUATES MEET IN SMALL GROUPS TO IMPROVE READING SKILL Prof. Robert M. Bear is in charge of the program for speeded reading that is given to students. The objectives of his work and gratifying results already achieved are described inthe accompanying article by Mr. Bear whose guidance for adult readers has attractednational interest.

PROFESSOR OF PSYCHOLOGY

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class Notes1936*

January 1942 By EDWARD T. CHAMBERLAIN JR. -

Article

ArticleWar Measures Adopted

January 1942 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

January 1942 By Craig Kuhn '42. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1911*

January 1942 By PROF. NATHANIEL G. BURLEIGH -

Class Notes

Class Notes1937*

January 1942 By DONALD C. MCKINLAY -

Class Notes

Class Notes1917*

January 1942 By EUGENE D. TOWLER