Pioneer Schoolmaster

To the Editor: While out in Indiana a while ago, I dropped into the Administration Building at Evansville College. On the right-hand wall of the entrance hall I saw a bronze plaque which read: In Memory of Daniel. Chute Graduate of Dartmouth College, Pioneer Schoolmaster, who taught public school in Evansville in the little red schoolhouse built in 1821 on the public square near Third and Main Street, and in acknowledgment of the generous gifts made to Evansville College in 1918 by his son, Haller T. Chute.

Daniel Chute was a graduate of Dartmouth in the Class of 1810. Most alumni have read of the educational influence exerted throughout the country by early graduates of the College, and this instance, it occurred to me, might be one that is not generally known.

New York, N. Y.

Opening Wedge?

To THE EDITOR: Is it possible that one item among the contents of the October issue of the MAGAZINE is suggestive of something more to come? I refer to the review by Dean Morrison of the book The Idea and Practice of General Education.

To me, wishfully no doubt, it was more than a review of a recent contribution to the literature of education. Could it be a cautious opening wedge later to be expanded into a discussion of liberal arts education at Dartmouth in terms of accumulative knowledge of and experiences with advances in liberal arts education over the years—all this for the enlightenment of alumni who have remained interested since graduation but who have, mere or less of necessity, been dissociated from the formal educative process in our liberal arts college.

I am not unaware, of course, that the MAGAZINE has from time to time published articles centering about the work of the several departments. Stimulated partly by controversial reasons, articles have likewise appeared to justify or explain the genesis of such extra-departmental efforts as the Great Issues course.

What I have in mind, however, is not quite satisfied by either of these. It is not even easy to make clear that what I have in mind is important, and different from information heretofore given. An effort to explain should in no way be considered as adversely critical of Dartmouth education. It is merely that I (and perhaps other alumni) would be very much interested in learning more fully than I presently can without becoming an undergraduate again (I'll take that if you can arrange it) of classes, courses, curricula at Dartmouth in 1951. I knew a little of them thirty years ago. I know a little about them todayjust enough to wish I knew more.

Specifically, two points of stress by Dean Morrison will serve to illustrate—the nature of the curriculum and, may we say, the teaching requisites at the University of Chicago.

Dartmouth is not the University of Chicago; it is not St. John's College in Maryland—and I for one should not wish it to attempt to become that which it is not. Nevertheless, I am sure that official Dartmouth has not been averse to acceptance of progress whether it emanates from the findings of others or from the results of its own experimentation. As a matter of fact, in the column next to the book review under discussion, the alumnus sees a listing of current appointments of divisional as well as departmental chairmen, and on a continuing page notice of the departure of a Dartmouth professor to study certain implications of general education.

But while basically the principles of general education are not difficult to grasp for the alumnus who has not read much in recent revealing publications, these principles (and practices) are somewhat foreign to his own academic experiences. Some experimentation has, of course, been attempted for many years, long before the present terminology became popular. Dartmouth men of the twenties no doubt recall two compulsory freshmen courses—Citizenship and Evolution. Puzzling as they were to many students and crude as their presentations may have been, they represented worthy efforts to give all students a commonality of background.

Sometime during the intervening years these courses disappeared, but Dartmouth now has a Great Issues course, comprehensive examinations, and divisional as well as departmental organization. I am sure there is much about the workings of these and about other current practices worthy of informed discussion on a less than technical plane.

Other (lower) educational levels are beginning to discover the values of an informed lay citizenry for a sympathetic understanding of public education. There is little reason to believe that collegiate undergraduate education would not similarly benefit from an informed alumni "citizenry." The old grad having occasion to study the Dartmouth catalogue may read descriptions of the Eccy or French 11 or Chem 1 of today without in the least being able to project himself into the classroom experience of young Mr. Dartmouth, into the young man's total college experience. Here, then, being uninformed, he is puzzled; and being puzzled, his enthusiasm may lag.

Reference to the classroom suggests the other point, teaching. What kind of teaching is being done and stimulated at Dartmouth? The question is not one of good teaching or bad teaching by individuals. There is no more reason to expect all teachers to be good teachers than to expect all business men or doctors or lawyers to be good ones.

Rather, the alumnus may be interested in the "how" of the Dartmouth teaching. Dean Morrison refers to his text and quotes one of the authors: "There is (at Chicago) continued experimentation, with the objective of devising increasingly effective teaching methods." This cannot be uniquely Chicagoan. Yet this cannot be understood from catalogue reading nor very adequately from casual conversation with undergraduates.

Upper Monte lair, N. J.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

November 1951 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR -

Article

ArticleTHE COLLEGE

November 1951 By John Hurd '21 -

Article

ArticleA Free Man Is Answerable

November 1951 By President Dickey -

Article

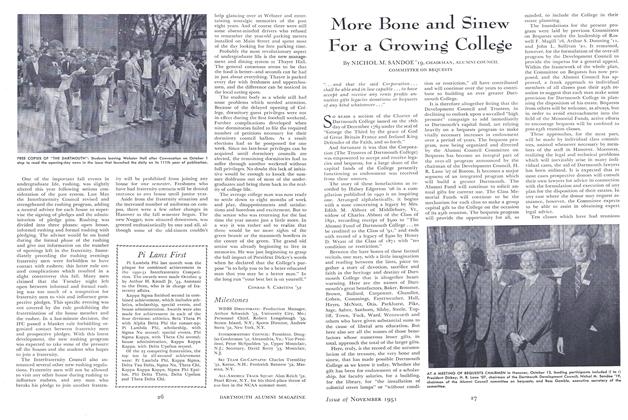

ArticleTo the Top of McKinley

November 1951 By JERRY MORE 52. -

Article

ArticleMore Bone and Sinew For a Growing College

November 1951 By NICHOL M. SANDOE '19 -

Article

ArticleAmbrose White Vernon

November 1951 By DONALD BARTLETT '24

Letters to the Editor

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorCOMMUNICATIONS

June, 1910 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorA SUCCESSFUL DARTMOUTH COACH

December 1916 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorSENIORS AND THEIR WANTS

November, 1922 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters

December 1987 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters

May/June 2008 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorReaders React

MARCH | APRIL 2014