The cultivation of original thought fuels the institutions growth and prosperity.

THERE ARE CERTAIN PARALLELS between the workings of Dartmouth and the process of evolution: In order to survive and thrive as an institution of higher learning, it is imperative that we have intellectual diversity. Here's why: Evolution teaches us that it is a species' varied genetic composition that enables it to overcome challenges to survival. A classic example is the finches Darwin discovered on the Galapagos Islands. Only those with beaks big enough to crack the large nuts that withstood a drought survived and multiplied, while small-beaked finches died out.

Like species, institutions must adapt. At Dartmouth we are constantly facing challenges to recruit a top-notch faculty and student body in order to thrive as an institution of higher learning. Species need genetic variation to survive challenges; institutions need intellectual richness. This is an aspect of Dartmouth's diversity mission that is often overlooked. Diversity for a college isn't just about diversity of race, ethnicity, religion and background. These are factors that go into creating a diverse faculty and student body, but the real goal in seeking out these variations is to create a wealth of ideas.

Of course such comparisons have their limits and are never perfect. Natural selection ultimately works to reduce diversity. That is why mutations are so crucial to a species, keeping the diversity present for future challenges and in a way almost fighting off the tremendous pressure toward singularity. Similar stabilizing forces leading to greater species diversity come at the ecological level. The richest and most productive communities found on earth—places such as tropical rain forests and coral reefs—owe their robustness, their longevity and their ability to adapt successfully to change to the diversity they enjoy. Conversely, ecologists have shown repeatedly that reducing community diversity—say, by experimentally removing one or two species—results in instability, a further reduction in diversity and lower productivity. Achieving true diversity is complex and dynamic.

There is another striking parallel between organizational processes and the operations of natural selection that we should take to heart. Faced with the challenge of preparing Dartmouth—or any institution—for future survival, leaders start forming committees and holding meetings, all in order to come up with a design for the future. But if we look at the process of natural selection, we realize that a biological species is not a designed creature. It is basically a Rube Goldberg device—a collection of adaptations produced through ad hoc accommodations made possible by random genetic variations over millions of years. If something works, it stays—like the large-beaked finch. The genetic variation that occurs in any given species lays the groundwork for the next challenge.

Advancement by design works no better in higher education than it does in the natural world. Change in higher education comes about by assuring that we have a variation of ideas as a core institutional value. Institutions that decide there is only one set of ideals, one viewpoint about the human condition, tend to become incapable of developing or adapting to new ideas. It is the belief that there is only one view that makes adapting to the future impossible.

Here views are wonderfully varied. Over the years Dartmouth has succeeded because students and faculty have reacted to challenge with vigor and purpose, redirecting the College to new heights. The forces that allow for intellectual variation are alive and well. But we must be vigilant in protecting not only diversity of ideas but an understanding of how adaptation is key to survival. We have created the framework for rigorous debate by having opposing views at the same institution. In addition to recognizing these differences, we must be willing to value the other side and adapt when necessary. It's a tricky balance. Two opposing ideas that are not open to adaptation will kill off the species just as rapidly as having a single wrong idea.

I see that achieving this balance is another thing that comes about not by design but by recognizing and accepting freedom of expression. In modern life, where ideas and capacities to change both personal and social agendas happen within decades rather than centuries, there is a particular need to accept the risks involved in new ideas—ideas that must be tempered with established wisdoms.

A friend of mine once quipped about the futility of business plans and strategic planning: "The one value of a business plan is that at least one way the business will not work has been articulated." Charles Townes, the Nobel Laureate who invented the laser, once observed, "The wonderful thing about a new idea is that you don't know about it yet." When these two insights are taken together one has the proper setting for being inventive and growing. I hope we can have more of both at Dartmouth.

MICHAEL S. GAZZANIGA is director ofDartmouth's cognitive neuroscience program.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

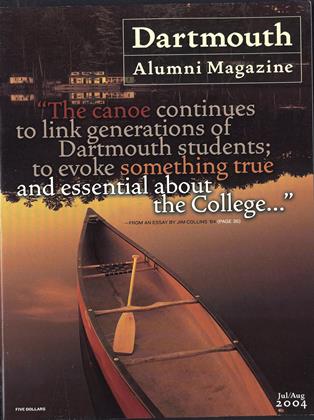

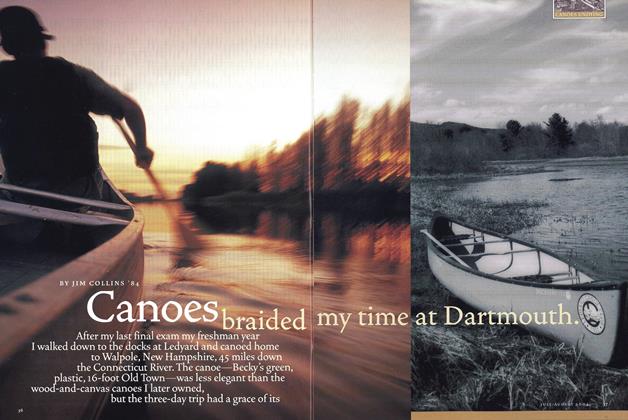

Cover StoryCanoes Undying

July | August 2004 By JIM COLLINS ’84 -

Feature

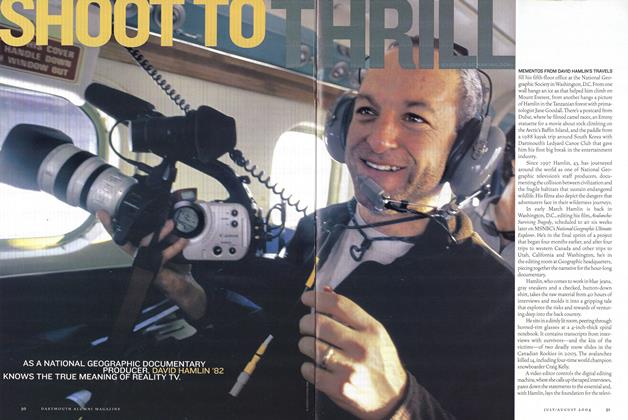

FeatureShoot to Thrill

July | August 2004 By DAVID MCKAY WILSON -

Feature

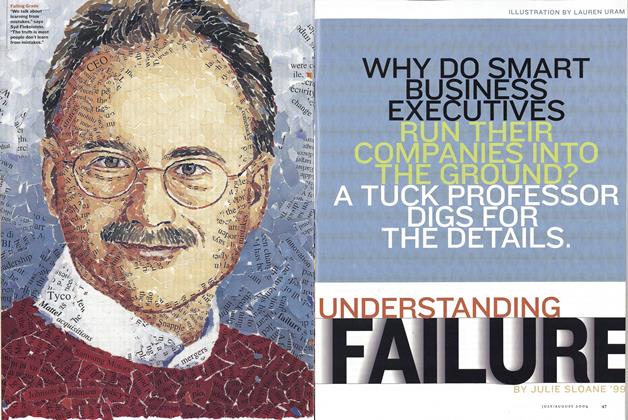

FeatureUnderstanding Failure

July | August 2004 By JULIE SLOANE ’99 -

Feature

FeatureOn The Water

July | August 2004 By JIM COLLINS '84 -

Faculty Opinion

Faculty OpinionTrade, Jobs and Politics

July | August 2004 By Douglas A. Irwin -

Sports

SportsYouth at Risk

July | August 2004 By Irene M. Wielawski