Dr. Brodie Gives Realistic Account of Naval Strategy; New Discussion of Lawyers and the Law Reviewed

EGY, by Bernard Brodie. Princeton University Press, 1942, 291 pp., $9.75.

IN HIS PRESENT BOOK the author of the distinguished Sea Power in the Machine Age sketches brilliantly the essentials of naval warfare. With the same penetration and clarity which marked his earlier work, he explains the functions of sea power, describes its weapons and their uses, shows in what command of the sea consists, tells how shipping is attacked and defended, deals with the problem of bases for surface and underwater and air craft, analyzes the tactics of fleet actions, and discusses the qualities of the fighting men.. Principles are supported throughout by telling illustrations drawn from the present war and other conflicts at sea. The book is in itself such a masterpiece of economical expression that one cannot pretend really to "review" it. The reader finds himself in the hands of a thorough student who gives a sane, rapid, and even a gripping account of his subject.

The fact that this book deals with a much broader subject than air power alone indicates that Dr. Brodie does not expect air power to become the whole show in the visible future. Frequently the analysis is brought to bear on the "Seversky" thesis of victory through (almost) unadulterated air power. One of the most interesting chapters, an abridged version of which appeared in The SaturdayEvening Post, inquires "Must All Our Ships Have Wings?"—and the answer is NO. Indeed, when he comes to the air-minded men who suggest that during fleet engagements the battleship is found where the general who got the croix de guerre was, the author is able to radiate some warmth as well as light. He tells why the battle wagon, or the fleet itself, for that matter, need not be exactly "there" in order to wield a powerful influence, and why a combination of different weapons, including dreadnoughts, can win with less outlay of blood and treasure than can unmitigated air power. It is not for the reviewer to complain that this argument may provide almost too much comfort for the "brass hats" for, as the author suggests, the attacker is likely to suffer heavier casualties than the defender. Still, a question may be in order: have the two sides to the air power controversy ever squarely joined the issue, that, is, the "right" proportions of different tools? Would we have been better off, to enter this war with 15 carriers and 8 battleships instead of 8 carriers and 15 battleships? Could we begin the argument there?

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

Article'Round the Girdled Earth

October 1942 By John French JR. '30 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorLetters from Tom Braden '40

October 1942 -

Article

ArticlePresident's Address Opens 174th College Year

October 1942 -

Article

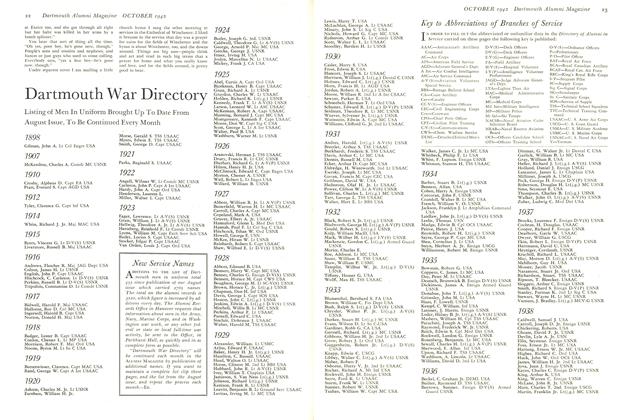

ArticleDartmouth War Directory

October 1942 -

Article

ArticlePay-As-You-Go Taxation

October 1942 By BEARDSLEY RUML '15 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918*

October 1942 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR