By Jerry Donohue '41. New York: JohnWiley & Sons, 1974. 436 pp. $22.50.

Aristotle once proposed that all things material were composed of four elements: earth, water, air, and fire. The appealing simplicity of this scheme failed the test of time, however, and noW we are burdened by over one hundred elements. These include substances as commonplace as carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen and as unfamiliar as technetium, osmium and dysprosium; but, alas, they include neither earth nor water nor air nor fire.

What Professor Donohue has done is to collect into one convenient volume the results of the efforts of a whole host of people who, over the past 60 years, have discovered the arrangements of the atoms in the solid phases of these elementary substances. One might suppose that the elementary solids, each limited as it is to atoms of only a single kind, would be blessed with rather straightforward structures and thus be rather bland fare for a book-length discussion. But turn to the section on sulfur and explore the devilish extravagance of variety which characterizes the crystallization of that element! (By the way, a significant portion of the original structural research on elemental sulfur has been done by Donohue and his students.) Or look for the discussion of carbon, perhaps expecting only to find the details of diamond and graphite, and discover such oddities as hexagonal diamond, rhombohedral graphite, chaoite, and several more.

Donohue's book is an exhaustive survey of a large body of literature, carefully presented with clear descriptions, remarkably fine illustrations, and complete documentation. It is unusual in that it preserves a sense of history; a great many mistakes and false starts were'made as these puzzles were unraveled, and the author has recorded these.

My criticisms are two. The first is that the book would be more helpful had Professor Donohue suggested on the basis of his long experience which determination among the many reported for some of the structures is likely to be the most reliable. The second criticism, really a most unfair one, is that the author straight - forwardly presents the facts but avoids the question of why the structures are what they are. But to add this as a goal would have lengthened the book at least ten-fold, and much of the interpretive material would be but interesting conjecture. Indeed, one of the great strengths of the book is that it displays nagging structural problems in such bold relief that it will be difficult for theoreticians to avoid confronting them. And so the interpretive material will be generated in due course.

Professor Donohue's book will never make a Perceptible dent in the commuter-train-reading market, but it will be a valuable reference work for physical scientists interested in the solid state.

Dartmouth Associate Professor of Chemistry,Mr. Soderberg teaches courses in InorganicChemistry and Topics in Advanced InorganicChemistry.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureDartmouth De Gustibus: More Food for Thought

December 1974 By JOAN L. HIER -

Feature

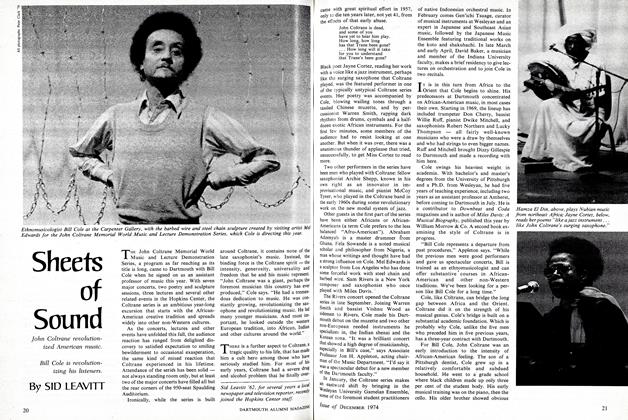

FeatureSheets of Sound

December 1974 By SID LEAVITT -

Feature

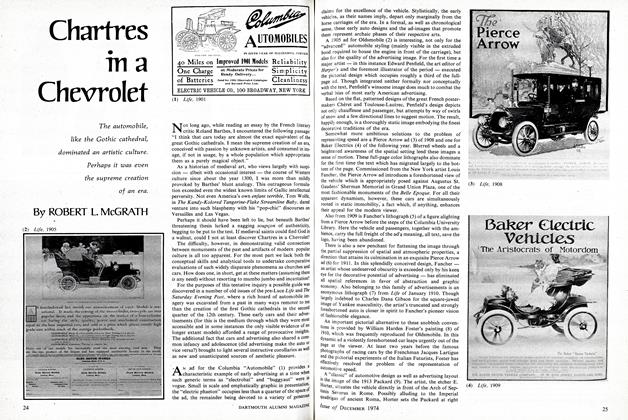

FeatureChartres in a Chevrolet

December 1974 By ROBERT L. McGRATH -

Feature

FeatureOur Crowd

December 1974 -

Article

ArticleBig Green Teams

December 1974 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1949

December 1974 By PAUL WOODBERRY, CHARLES S. KILNER

Books

-

Books

BooksNotes on a literary equilibrist whose translations, according to one author thus translated, may rival the original.

January 1977 -

Books

BooksASBESTOS PHOENIX.

DECEMBER 1968 By ALEXANDER LAING '25 -

Books

BooksREBIRTH OF A NATION. THE ORIGINS AND RISE OF MOROCCAN NATIONALISM,

APRIL 1968 By CHRISTIAN P. POTHOLM II -

Books

BooksNO TIME FOR SCHOOL, NO TIME FOR PLAY: THE STORY OF CHILD LABOR IN AMERICA.

NOVEMBER 1972 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksInfested With Sharks

June 1980 By Joseph W. Bishop Jr. ’36 -

Books

BooksTHE ORGANIZATION OF JUDICIAL POWER IN THE UNITED STATES.

NOVEMBER 1969 By RICHARD MORIN '24

Books

-

Books

BooksNotes on a literary equilibrist whose translations, according to one author thus translated, may rival the original.

January 1977 -

Books

BooksASBESTOS PHOENIX.

DECEMBER 1968 By ALEXANDER LAING '25 -

Books

BooksREBIRTH OF A NATION. THE ORIGINS AND RISE OF MOROCCAN NATIONALISM,

APRIL 1968 By CHRISTIAN P. POTHOLM II