For the second time within the space of a quarter century Dartmouth College faces the problem of maintaining a college under war conditions. President Hopkins candidly recognizes the impossibility of attempting to conduct "college as usual" and stresses the imperative necessity of changing habits to meet unusual conditions. About the only thing that is "as usual" at the moment of writing seems to be the number of students in actual residence at Hanover-about half of the customary 2000-plus being men in training for the navy under the direction, not of the college, but of the Navy Department itself. With the process of indoctrinating, or otherwise instructing, the men thus engaged, the College itself has nothing to do, of course. What it is concerned with is the manner of instructing the other half of the resident student population—the actual students of Dartmouth, in need of something radically different from the usual needs in the way of education. It is there that the idea of "college as usual" breaks down.

The stress of the times requires some- thing foreign to the old-time demand for training cultivated gentlemen with ap- preciations suited to the full enjoyment of living after a living has been earned. In a way, the current task is simpler. It has to do with the stern business of turning out graduates well fitted to bear a hand with the practical tasks of the times—primarily that of contributing efficiently to the war effort. The practical certainly dwarfs the cultural for the moment, and must until such time as normal conditions of human living return. The one topic uppermost in all minds just now is winning the war. After it is won we can turn to other things, but we cannot turn to them now, or do much more than bear them in mind as things of future concern. The job confront- ing the United Nations is so vast that it excludes all else. If the war were not won, nothing else would be worth considering. To win is the great and first command- ment.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleThe American Dream: Growth of a Nation

November 1942 By KENNETH ALLAN ROBINSON -

Article

ArticleCollege Finances Sound

November 1942 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918*

November 1942 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR -

Class Notes

Class Notes1936*

November 1942 By NORBERT HOFMAN JR., JOHN E. MORRISON JR. -

Sports

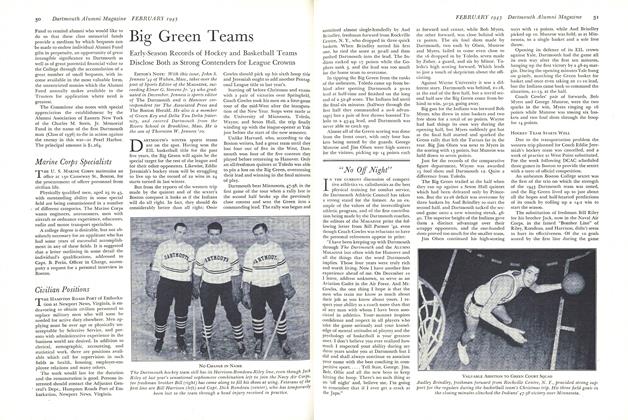

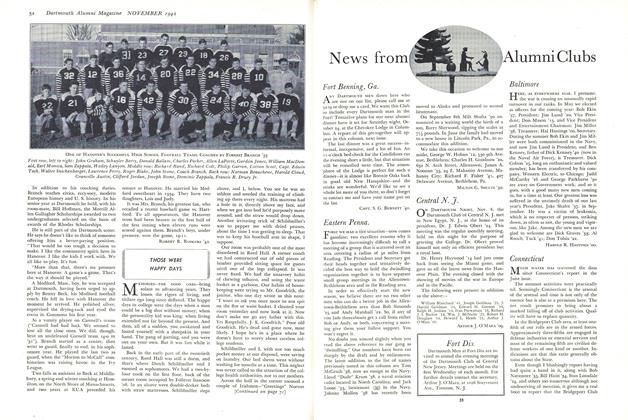

SportsBig Green Teams

November 1942 By ELMER STEVENS JR. '43. -

Sports

SportsTHOSE WERE HAPPY DAYS

November 1942 By Jack Childs '09

P. S. M.

-

Article

ArticleSea-Anchor for Dartmouth

January 1943 By P. S. M. -

Article

ArticleMemorializing Wheelock

December 1943 By P. S. M. -

Article

ArticleIntercollegiate Interim

January 1944 By P. S. M. -

Article

ArticleDos Pou Sto

February 1945 By P. S. M. -

Article

ArticleCultural vs. Practical

April 1945 By P. S. M. -

Article

ArticleIs Too Much Enough?

December 1945 By P. S. M.