Questions of Kind and Scope of Truths Discussed as Problems on Which the Nature of Our Civilization Depends

by PhilipWheelwright, Cleanth Brooks, I. A. Richards, Wallace Stevens, ed. Allen Tate,Princeton Univ. Press, 1942, pp. 135, $2.00.

FROM THE SEVENTEENTH century we directly inherit many of our greatest blessings and many of our greatest ills. When we think of Galileo, Harvey, Newton, Descartes, and Hobbes, the blessings are obvious. They may be summed up in a word: science. But the ills, though no less real, are only now attracting widespread attention. Chief among them is our modern specialization of belief. More and more we have come to regard as "true" only what is susceptible either of mathematical demonstration or of that repeated inductive illustration which for most natural scientists constitutes proof. Less and less do we regard as "true" whatever comes to us without scientific credentials. The authority of religion declines for many people into a mere persistence of custom. And literature—until the seventeenth century, considered the vehicle not only of "truth" but of the kind of "truth" most necessary to taan as more than animalhas since Descartes and Hobbes been increasingly relegated to a truant hour role, as mere entertainment or relaxation.

Until recently, this state of affairs was happily regarded on all hands as "progress." But now, doubts are rapidly hardening into a sense of impending cultural disaster. The conviction grows that the truths of natural science, essential though these are to the continued existence of the human multitudes who could never have been born without their aid, are yet not of a kind by themselves to nourish the good life in most men and all nations. Man cannot live by relativity alone. Gravity moves us and may on occasion save us; but it cannot make us worth saving. It has not even been proved that hormones can do that. Many penetrating minds are today addressing themselves to the questions posed by our dilemmatic situation: questions such as, what realities or values are symbolized by the word "truth"? Must all "truths" be of the same kind? What kinds of "truths" are necessary to man? What is the relation between some of these "truths," on the one hand, and religion and literature—especially poetry—on the other? What is the role of imagination in the discovery of "truth," and of figurative or metaphorical language in its communication? These matters are being discussed, not as mere themes for ingenious discourse, but as problems on the answer to which depends the nature of our civilization.

The four lectures assembled in this book, delivered at Princeton University as The Mesures Series in Literary Criticism for 1941, approach these questions from various angles. Professor Wheelwright of our own Dartmouth Department of Philosophy devotes his lecture to the statement and illustration of the idea that human experience is not comprehended within what he calls the empirical or horizontal dimension, in which the individual thinking mind perceives the "things, relations and ideas" encountered in "our everyday commonsense world." To comprehend experience we require also a vertical dimension, in which the community mind experiences and apprehends mystery. Any actual moment of human experience is only adequately interpreted if it is referred, even though in proportions that vary, to both of these fundamental axes or guiding principles. By contrast with Professor Wheelwright's considerable use of religious illustrations, the other three writers confine themselves mostly to literary illustrations (and with Mr. Stevens, illustrations from the fine arts). Professor Brooks shows that the paradoxical implications present in much (he might say, "all") good poetry testify to the wholeness, the centrality, of the poet's vision of truth. Dr. Richards discusses chiefly that part of the communication of language which eludes us if we are not aware of the effects which words used in certain ways have upon one another: the

"inter-inanimation of words" is a term he often uses in his book to denote this inter-action. And finally, Mr. Stevens discusses the necessity for literature of both realism—a sense of "fact," and of imaginative nobility, grounding his assertion on the larger claim that both elements are necessary to the life of any civilization.

All of these lectures are thoughtful; all are suggestive. The first two excel in a limpidity of style and clarity of order that make them the easier to grasp at a first reading. The last two exhibit a greater obliquity of approach; the reader unwraps them as if they were parcels, and only near the end of his activity does he clearly discern the outlines of what is to be disclosed. But these differences in strategy add to the interest of the book, and it deserves to be read widely and thoughtfully.

"ECONOMIC SIDE OF DEMOCRACY"Will be the subject of the talk by Prof. EarlR. Sikes on the Hanover Holiday programthe week of May 11-15. The general topicof the week's program of faculty talks anddiscussions will be "The Making of American Democracy." Hanover Holiday thismonth will begin the day after the Commencement exercises May 10 and will conclude Friday evening, May 15, when theclass reunion week-end begins.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

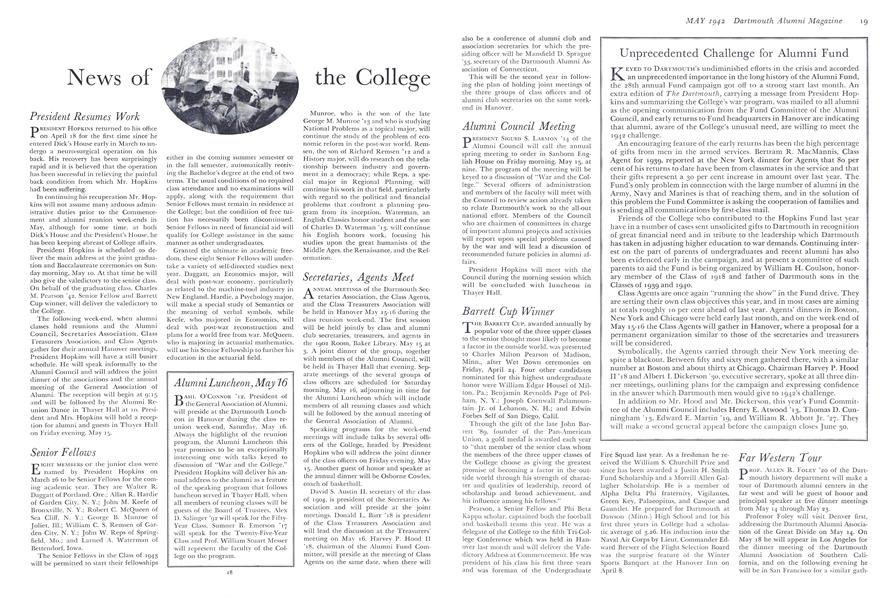

ArticleDartmouth Broadcasting System

May 1942 By WILLIAM J. MITCHEL JR. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1917*

May 1942 By EUGENE D. TOWLER, ARTHUR P. MACINTYRE -

Sports

SportsBig Green Teams

May 1942 By James L. Farley '42 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918*

May 1942 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, RICHARD A. HOLTON -

Article

ArticleWar Program Takes Hold

May 1942 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

May 1942 By Edward J. Rasmussen '42

F. Cudworth Flint

-

Books

BooksSADDLING PEGASUS

JANUARY 1932 By F. Cudworth Flint -

Books

BooksBEAU-POIL AU MAROC

June 1940 By F. Cudworth Flint -

Books

BooksSELECTED POEMS

October 1951 By F. Cudworth Flint -

Books

BooksTHE MODERN CRITICAL SPECTRUM.

DECEMBER 1962 By F. CUDWORTH FLINT -

Books

BooksTHE WORLD, THE WORLDLESS.

JUNE 1965 By F. CUDWORTH FLINT -

Books

BooksTHE GEORGIAN REVOLT: RISE AND FALL OF A POETIC IDEAL, 1910-1922.

NOVEMBER 1965 By F. CUDWORTH FLINT

Books

-

Books

BooksFaculty Articles

June 1956 -

Books

BooksALL THE BEST IN SCANDINAVIA.

OCTOBER 1968 By BETTY HOEG HAGEN -

Books

BooksAND HOW DO WE FEEL THIS MORNING?

JULY 1964 By CLIFF JORDAN '45 -

Books

BooksTHE CORFU INCIDENT OF 1923: MUSSOLINI AND THE LEAGUE OF NATIONS.

JULY 1966 By GENE LYONS -

Books

BooksAN INTRODUCTION TO MONEY AND BANKING

OCTOBER 1972 By MICHAEL R. DARBY '67 -

Books

BooksHMS CEPHALONIA.

OCTOBER 1969 By VINCENT E. STARZINGER