by WillardConnely '11, Cassell and Company, London,1939, 479 pp., 15 shillings net.

One of the popular convictions about Lord Chesterfield is that he was distinguished chiefly for an urbane unfaltering courtesy which Boswell called "glossy politeness." A legendary figure, regarded as if he had been the chief glass of fashion and mould of form in the eighteenth century, he has now become an appropriate godfather for swank overcoats, soft divans, and mildly satisfactory cigarettes. Though partly true, this legend ignores the fact that the real Earl was always tough and often bitterly rude. More true, and more important, is the popular conviction that Chesterfield had an unlimited faith in the power of education to transmogrify human individuals into a standard type. Perhaps he derived this faith from his cook, who (as Mr. Connely informs us) had a recipe "How to make a pig taste like a young wild boar. The procedure was to pour down the pig a liquor compounded of thyme, sage, bay leaves, and sweet marjoram; then whip the pig to death." By the letters that Lord Chesterfield wrote to his lumpish son, he valiantly strove to convert a porcine creature into an elegant gentleman, in the faith that

"Tis education forms the youthful mind: Just as the pig is bent, the hog's refined.

But "the true Chesterfield" excelled popular conceptions. The glossily polite arbiter and the pig-transforming pedagogue were only two facets of the great Earl's many-sided character. Mr. Willard Connely, who is the Director of the American University Union in London, has wisely used his ripe scholarship and his excellent opportunities for research to give us a biography which portrays the Earl at full length, in great detail, and without misrepresentative simplification. Some readers may find the volume too long, the detail too bewildering, and may regret that TheTrue Chesterfield is less original or less critical than Mr. Connely's previous biographies Brawny Wycherley and Sir Richard Steele. But enthusiasts for the eighteenth century will probably feel that The True Chesterfield is the best book Mr. Connely has produced, because it is the most thorough. Its aims are reflected by its title. Its method is carefully calculated to fulfil its aims. In the preface, the author declares:

"Beyond trying to be objective, I have sought to be consistently chronological. It seems to me that only confusion, not dramatic effect, is gained by composing a biography in layers of classified incidents. Long stretches in the life of a great man may be dull, monotonous, of little significance; these may be condensed, but are not to be anachronized, lest the impress of the character be thrown out of joint and the reader retain only dislocated truth."

We may question this doctrine, and may cite such an example as DeLancey Ferguson's Pride and Passion (a lite of Robert Burns) to argue that excellent biographies have been composed "in layers of classified incidents"; but Mr. Connely's method commands respect by its results. The merits of his book are apparent when it is compared with other recent biographies of Chesterfield which are perhaps more easily readable and more immediately impressive, but more partial or more biassed. Roger Coxon's Chesterfield and His Critics (1925) did little more'than vindicate the Earl's reputation from the charges of dishonesty and frivolity; Bonamy Dobree's brilliant sketch (1932) emphasized the Earl as "the pattern of a certain type of man, the consciously civilized, controlled" and self-constructed aristocrat; and Samuel Shellabarger's Lord ChesterChesterfeld (1935) was designed to convince its readers that the image in which the Earl created himself was ungodly. Mr. Connely does not take issue with any of these biographers; on the whole, his interpretation agrees with theirs; but he takes wider ground, refrains from telling us what to think, and does not usurp the reader's right to construct a synthesis based on the data which the biographer supplies. Nor is the reader obliged to construct a synthesis (which would probably be false, anyhow, like most of. them); he can be satisfied to take the stuff as it comes. From synthesis-mongers and all their works of abomination, the reader may turn with pleasure to Mr. Connely's admirable description of Madame de Tencin's salon, and see the eighteenth century alive again:

"In beige gown and apron, and blue satin headdress, Madame de Tencin liked to bring in the tea herself. Guests circled before the fire, above which hung a convex mirror, and on the mantel an ormolu clock, and at either side, instead of candlesticks, two globes fixed to the wall. There sat old Fontenelle, the link between his departed uncle Corneille and the advancing Voltaire, Fontenelle the exquisitely judicial, brows soaring, eyes a little narrowed; Joseph Saurin the dramatic poet, a brisk restive man of thirty-five, up from his chair and telling off on his fingers the points of an essay which he objected to, or possibly approved; the ebullient young Crebillon, chattering about his own works of romance; and not least, Chesterfield's well-beloved friend Montesquieu, friend of freedom and foe of bigotry, who with his perruque off might have been taken for Julius Caesar, with his long nose and slanting forehead. Thus the wits met, read their verses, heard them applauded or denounced: Chesterfield heard Fontenelle read two of his plays. There was something about the house of Claudine de Tencin that the Earl never got in England, not even in Pope's feasts of reason at Twickenham."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

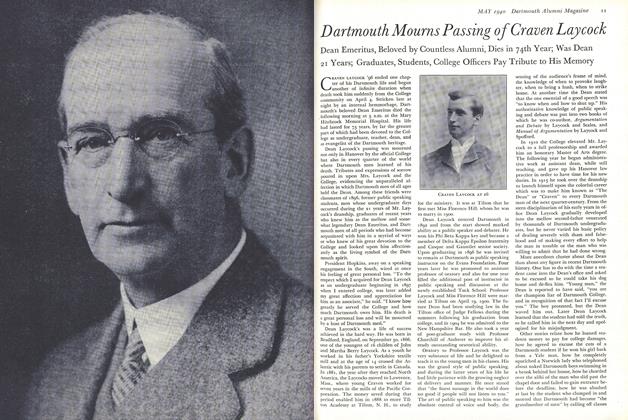

ArticleDartmouth Mourns Passing of Craven Lay cock

May 1940 -

Article

ArticleI Found Seven Latinos

May 1940 -

Article

ArticleJohn M. Mecklin, Teacher

May 1940 By Thomas W. Braden '40 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1915*

May 1940 By CHARLES R. TAPLIN, RUSSELL B. LIVERMORE -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

May 1940 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918*

May 1940 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, H. WARREN WILSON

H. M. Dargan

-

Books

BooksSATIRES AND PERSONAL WRITINGS

MAY 1932 By H. M. Dargan -

Books

BooksTHE HOUSE OF THE DAMNED

January 1935 By H. M. Dargan -

Books

BooksTHE MOTIVES OF NICHOLAS HOLTZ

March 1936 By H. M. Dargan -

Books

BooksSOFT MONEY

October 1939 By H. M. Dargan -

Books

BooksWHERE THERE'S SMOKE,

April 1947 By H. M. Dargan -

Books

BooksYOUNG GEORGE FARQUHAR: THE RESTORATION DRAMA AT TWILIGHT,

June 1949 By H. M. Dargan

Books

-

Books

BooksFaculty Publications

NOVEMBER 1929 -

Books

BooksHUGH LOFTING'S TRAVELS OF DOCTOR DOLITTLE.

JANUARY 1968 -

Books

BooksTHE FALL OF SAIGON

June • 1985 By David Bowman '63 -

Books

BooksTHE FEAR OF GOD.

November 1959 By FRANCIS W. GRAMLICH -

Books

BooksPUSHKIN THREEFOLD: NARRATIVE, LYRIC, POLEMIC, AND RIBALD VERSE. THE ORIGINALS WITH LINEAR AND METRIC TRANSLATIONS.

MAY 1973 By LUDMILLA B. TURKEVICH -

Books

BooksNEO-CONFUCIANISM, ETC.: ESSAYS BY WING-TSIT CHAN.

MARCH 1970 By SHU-HSIEN LIU