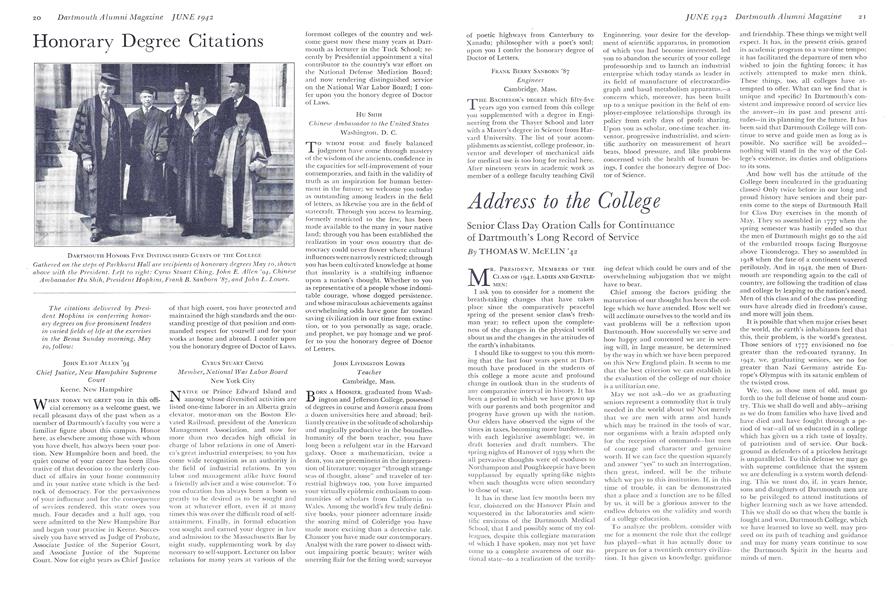

"Ideals Are Ultimately the Most Practical Things in the World," Dartmouth Trustee Asserts

IT is UNNECESSARY for me to state that you are now entering the ranks of the alumni and are very welcome thereto. It is likewise impossible for me to attain the proper mixture of reminiscence, congratulation, and paternal advice which would be appropriate in more conventional and happier years. The very fact that these exercises are held in May in itself indicates that the times are out of joint.

You will step from these halls into a chaotic world, beset with all kinds of troubles and problems. You will have your part in bringing the war to a successful conclusion and you will also have a part in settling the conditions of peace and preventing the recurrence of the kind of thing that has brought this war to pass.

I, of course, assume that we shall win. If I thought otherwise I would have no place here and anything that could be said would merely amount to surplusage.

During the last twenty years, the period since the last world war, the dominant political and social emotion in America has been fear of war. It has been fear of war and not love of peace, because the two things are entirely different. During this period the pacifists and other people opposed in all circumstances to armed conflict have had a field day. While pacifism may be very satisfactory to its adherents, it does nothing to remove the causes of war and unrest.

The fear of war resulted from adherence to a material ideal. That ideal was known as a "standard of living." A standard of living meant simply more appurtenances which conduce to the physical comfort of life. It seems to me perfectly logical and natural that in such circumstances young men thought nothing worth, fighting for. As a matter of fact, there is no reason why a young man should go out and fight for more Fords and electric refrigerators—because that is all it amounted to. On the educational side, the effort to develop man to the attainment of his destiny, entirely apart from traditional Christianity, showed itself to be completely sterile. There were so many opinions, views, and philosophies, bogus and otherwise, that people were unable to agree on any one thing. As a result they feared war because in war men die, and death is too high a price to pay for materialities.

Peace, as a result of all this, was regarded mainly as an opportunity for the exploitation of commercial possibilities—the making of money and various kindred attainments, with all the incidents of amusement and extravagance that were natural accompaniments.

If I were asked to define the past twenty years, I should define it as the "horse trading

era." The present condition of affairs is a perfectly logical outcome of the chicanery, trickery, and pull that have been characteristic of a considerable part of both public and private businesses. Indirection and special privileges quite naturally lead up to violence as the next step. Material prosperity was our watch-word regardless of anything else.

From the idealism of Woodrow Wilson we degenerated to the kind of normalcy expressed by the things I have been talking about.

My generation forgot some things and overlooked others which you can neither forget nor overlook, if there is to be an ultimately satisfactory result.

In the first place, we completely misconceived the nature of peace.

Peace is not merely a cessation of violence for the attainment of material comfort.

As a lawyer I like to define my terms. What is peace? What does it mean?

We know that the best thing we can wish for anyone who has died is "may he rest in peace." In olden times the salutation of "peace be with you" indicated the estimation in which it was held. The Lord Jesus Christ said "My peace be with you, My peace I give unto you." What did He mean? At the very time He made that statement men were slaughtering each other all over the world just as they are today.

The clue may be found in His statement that He gave not as this world gives. I think He meant that interior peace, based on conviction and faith, which armed a man against the things of this world, and made him impervious to famines, wars, cataclysms, and even death.

I think the kind of peace indicated by love of peace as opposed to fear of war means a peace in which men will have opportunities to advance justice and right, and every individual will have the chance to attempt, at any rate, the things which he thinks lie within his capacity. Above all things it must be a peace which will control war—a peace men are willing to fight to maintain. That today, as I see it, is the only kind of a peace worth having. That is the kind of a peace which would make the world safe for democracy. And yet when Woodrow Wilson said of the last war that it was a war to accomplish that end and a war to end war, we all indulged in some twenty years of derisive laughter.

I wonder who is laughing now? If anyone, it is, as one writer said, the ghost of Woodrow Wilson.

The second thing America forgot was that the line which was followed was contrary to the laws of her own growth.

After all, our government today is the oldest government in the world. When it was expressed in the Constitution in 1789, a burning zeal for democracy overran the whole world. The down-trodden and oppressed of every nation and every race wanted to come to the United States or set up a similar government in their own home lands. Democracy, as thus conceived, was a dynamic force.

By dynamic I mean, as one writer has expressed it, something like a man riding a bicycle—he must keep going or he falls down. After the last war this zeal for democracy abated and came to a standstill. Forgetful of the fact that the purpose of our constitution was, as Jefferson expressed it, to keep men free, various gadgets were added which diverted it from its original purpose. The result was that the same thing happened that always happens when we attempt to use a piece of machinery for something other than that for which it was created. Under the guise of giving the government back to the people we turned it over to pressure groups. The attempt was made to adapt certain processes of pure democracy—in itself the most tyrannical kind of government in the world—to our plan of representative democracy. We have now reached the point where we resemble Abraham Lincoln's locomotive. You will recall that it had only so much power and when the engineer wanted to blow the whistle he had to divert the steam from the wheels. For years we have listened to the discordant blasts of a forest of whistles instead of applying the energy and power in more constructive ways.

As our democracy has lost in fervor and become more or less static, other movements have taken its place—movements exemplified in all forms of totalitarianism.

We have attempted to accomplish our destiny by hugging our own liberty to our bosoms and taking the position that we could save it for ourselves regardless of the rest of the world. From a haven for the oppressed we sought to make ourselves a citadel for the preservation of our own- solely for ourselves. We thought we could isolate ourselves from the rest of the world and work out our own destiny independent of the fate of the rest of mankind.

Democracy, to some extent, is like Christianity. The man who says he has enough Christianity for himself without regard to the rest of the world invariably falls short. Paradoxically enough, the man who has not only sufficient for himself but also offers it to the rest of the world has just enough for himself from the Christian point of view. The same thing can be said of our democracy because it grew on the basis of unselfishness and generosity. The effort to isolate ourselves could not in the nature of things be successful. Its entire fallacy has been completely demonstrated by the march of events.

If I could say any one thing to you that I should like you to remember it would be this: Ideals are ultimately the most practical things in the world. When you come to do your share in making a just peace remember Cain's reply when he was asked where his brother Abel was. He said, as you may recall, "Am I my brother's keeper?" No answer was given. No answer was given because no answer was necessary. But the answer was—we forgot it and you must remember it—the answer was, "Yes, you are your brother's keeper."

First College Museum

Dartmouth College's first museum was a collection of "curiosities" of which President John Wheelock (1779-1815) was inordinately proud. Especially prized was a stuffed zebra, which had the habit of appearing in strange places, such as the roof of the chapel or the belfry of College Hall, thereby requiring laborious transportation back to its museum abode. Also dear to the presidential heart was another stuffed specimen, vaguely known as "the great bird." All this material has long since disappeared.

The text follows of Mr. Grant's talkat the luncheon meeting for seniorsand their fathers and the faculty inHanover at Commencement.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleCollege Graduates Return

June 1942 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1927 Has Its Quindecennial

June 1942 By DOANE ARNOLD '27 -

Class Notes

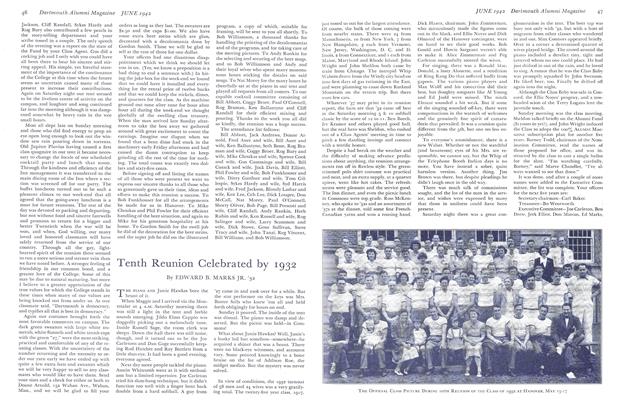

Class Notes1937 Holds Its Fifth Reunion

June 1942 By JOHN H. DEVLIN JR. '37 -

Class Notes

Class Notes'Seventeen's Silver Jubilee Wins Cup

June 1942 By MOTT D. BROWN JR. '17 -

Article

ArticleValedictory to Class of 1942

June 1942 -

Article

ArticleFirst War Class Graduates

June 1942

Article

-

Article

ArticleDINNER FOR AMBULANCE MEN

June 1917 -

Article

ArticleA WAH-HOO-WAH!

May 1940 -

Article

ArticleHANOVER CHARACTERS — 1963

NOVEMBER 1963 By ALLEN R. FOLEY '20 -

Article

ArticleNews Makers

Sept/Oct 2009 By BONNIE BARBER -

Article

ArticleThe Gift of Education

May/June 2002 By President James Wright -

Article

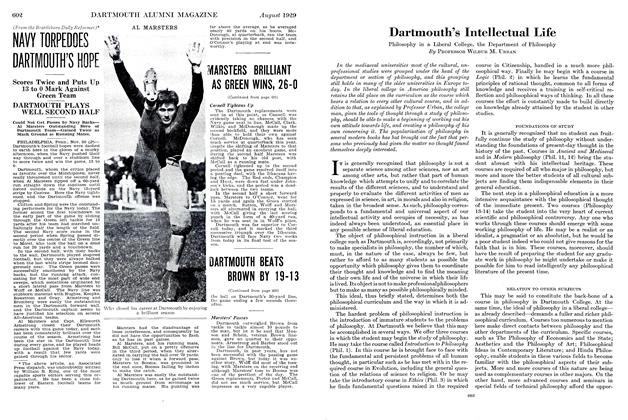

ArticleDartmouth's Intellectual Life

AUGUST 1929 By Professor Wilbur M. Urban