PRESIDENT HOPKINS wrote on August 15 in the Sunday Magazine of the NewYork Times a thoughtful article on the future of the American colleges as affected by the stress of war. His conclusion appears to be that it is wise to beware of streamlining as a permanent thing, useful and necessary as it may be in the mastering of a war emergency. Undoubtedly there will be pressure to protract the hurry-hurry policy after the war. Indeed, even without the impetus which war has given, there was a school of thought which insisted that too much time had been required for the attainment of the A.B. degree, and which maintained that two years—or three, at most—should be enough to spend on such attainment. It has been urgently argued that the old requirement of four years represented wasted time.

It is this which certain eminent figures in the educational field appear to challenge—President W. H. Cowley of Hamilton no less insistently than the president of Dartmouth. No one denies that in two years or so a student could be made to cover much of the ground traditionally represented by the degree of Bachelor of Arts; but it is suggested that such a degree, so won in that brief length of time, would not represent the intellectual value attached to the A.B. that had been more leisurely acquired. In fine the contention is that the four-year course, while it certainly postpones the earning period of the student, or delays his entrance into the specializing graduate schools, is not on that account to be regarded as time wasted. It is pointed out that some things cannot be hurried, but develop slowly from inception to fruitful maturity—most of all character in mankind. This, while an imponderable factor, is not to be waved aside as unimportant.

President Hopkins, as this writer sees it, is undoubtedly right. Devotion to the idea of a four-year course in the liberal arts colleges is by no means based exclusively on the fact that this has always been so, or on any reluctance to accept change where change is beneficial. It rests on the conviction that change is not to be accepted as beneficial merely because it is change, and on the fact that much is to be said for the unhurried and reasonably contemplative study of the things learned.

What needs to be guarded against is undue reverence for high speed and superficial efficiency. In the face of dire necessity, such as that involved in making a war for which America was lamentably unprepared, certain desirable things must be sacrificed momentarily and treated as—in Dr. Hopkins' phrase—"casuals of war." But we sacrifice them, not because those things are valueless, but only because for the time being we must. The colleges, like other institutions, have had to cut corners in order to make haste; have had to jettison part of the intellectual cargo for the attainment of an imperative end. It does not follow that in the less strenuous years of peace we should continue to act as if we were driven by the spur of war, and set for ourselves an ideal of breathless hurry when the need for hurry has passed. Man does not live by bread alone. The liberal arts colleges are less concerned with fitting men to earn their bread than for equipping them to enjoy it fruitfully for their environment when it has been earned. Some crops can be forced, and some cannot be; and among those ill adapted to the forcingbed are character and culture, without which human society would hardly be worth the saving.

THE CAMPUS TODAY PROVIDES STIRRING SCENES SUCH AS THIS RECENT REVIEW

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

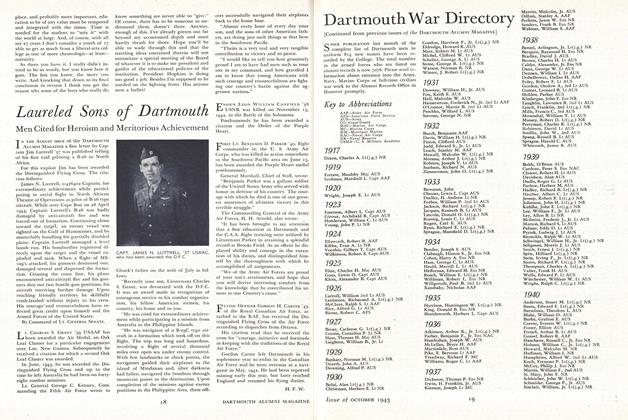

ArticleDartmouth War Directory

October 1943 -

Article

ArticleTHE GIFTED CROSBYS

October 1943 By L. B. RICHARDSON '00 -

Article

ArticleA LESSON IN ADAPTABILITY

October 1943 By H. F. W. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1937

October 1943 By JOHN H. DEVLIN JR., FRANCIS T. FENN, JR. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

October 1943 By EARNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR -

Class Notes

Class Notes1917

October 1943 By MOTT D. BROWN JR., DONALD BROOKS

P. S. M.

-

Article

ArticleSea-Anchor for Dartmouth

January 1943 By P. S. M. -

Article

ArticleThe Overmastering Need

February 1943 By P. S. M. -

Article

ArticleNot So Useless

August 1943 By P. S. M. -

Article

ArticleIntercollegiate Interim

January 1944 By P. S. M. -

Article

ArticlePractical Memorial

December 1945 By P. S. M. -

Article

ArticleRallentando

February 1946 By P. S. M.