There is room for debate concerning the unqualified validity of President Roosevelt's "fourth freedom"—which is usually called "freedom from fear." On its face it might seem that no one could quarrel with it. Certainly no one wishes to be continually afraid. What gives one to think is the recollection that in some aspects the fear of coming to want serves as the inexorable spur to thrift and endeavor, without which mankind might easily become indifferent and lazy. The church has never found any very efficient substitute for hellfire; and the world might discover that, lacking the incentive of stern necessity, its people suffered far more than they ever did because of their dread of an indigent old age.

When a professed New Dealer talks of "freedom from fear" he usually implies that he means freedom from the fear of want; and he seems to regard it as highly desirable that this fear be removed by the promise of a hand-out by a paternal government if the need arises, on which every man, woman and child may rely. There is little sympathy in New Deal circles for the ancient law that-he that doth not work shall surely not eat; and the admonition of the frontier vernacular, "Root, hog, or die," sounds like barbarity in the humanitarian ear. But is it, after all, desirable entirely to remove the fear of all penalties for unthrift? For a guess, this country would not be what it is today if its people had been "insured against want" for the past 300 years. There's little mercy in a spur, and much cruelty—but can we honestly do well without it? Can we differentiate accurately between the lame and the lazy?

Our Utopians may do well to moderate their zeal to give the federal government so much the aspect of a cozy home for the aged. After all, most men would hesitate to regard the security of a subsistence dole in old age as a satisfactory substitute for the chance to do better if they could, risky though that might be. No one does his best when it is felt that it makes little difference if he fails. Perhaps this fourth freedom—from fear of want—can be overdone and produce a cure worse by far than the disease. It will be said, of course, that insuring the unfortunate against penury would not prevent men from striving with all their might to make their way onward and upward, but as human beings are constituted it is probable that in many cases it would. Knowing that at worst one will not starve is a relaxing knowledge. Realizing that one will suffer if he doesn't struggle to keep going has certain virtues which rebound to the benefit alike of the individual and the race. Succor for the unfortunate no one would refuse; but this proposition to issue a blanket policy of insurance covering all mankind is something which it would be well to ponder before making it a basic platform of the American creed.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the Editor'Round the Girdled Earth

May 1943 -

Article

ArticleTHE LIBERAL ARTS COLLEGE

May 1943 By W. H. COWLEY '24 -

Article

ArticleBrief Biographies of Buildings

May 1943 By LEON BURR RICHARDSON '00 -

Article

ArticleFrom the Mailbag

May 1943 -

Class Notes

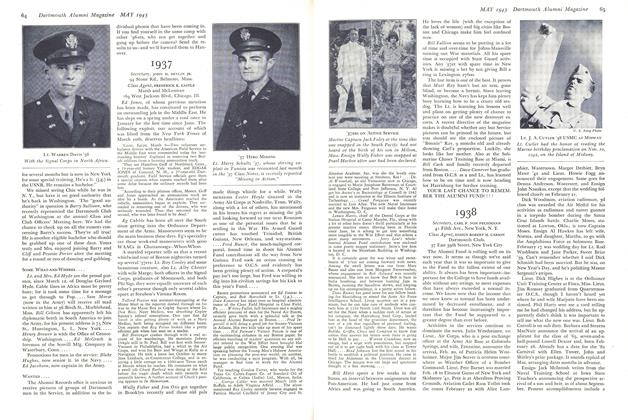

Class Notes1937

May 1943 By JOHN H. DEVLIN JR., FREDERICK K. CASTLE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

May 1943 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, RICHARD A. HOLTON

P. S. M.

-

Article

ArticleThe Overmastering Need

February 1943 By P. S. M. -

Article

ArticleLooks a Fertile Field

February 1943 By P. S. M. -

Article

ArticleWorship of the Plan

April 1943 By P. S. M. -

Article

ArticleWe Shall Because We Must

May 1943 By P. S. M. -

Article

ArticleHurry, Hurry, Hurry!

August 1944 By P. S. M. -

Article

ArticleDartmouth Undying

October 1945 By P. S. M.

Article

-

Article

ArticleALUMNI SONS IN FRESHMAN CLASS

November, 1025 -

Article

ArticleDartmouth Poet

November 1956 -

Article

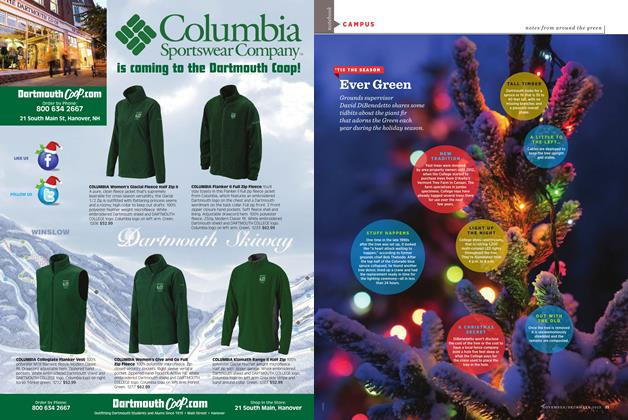

ArticleEver Green

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2013 -

Article

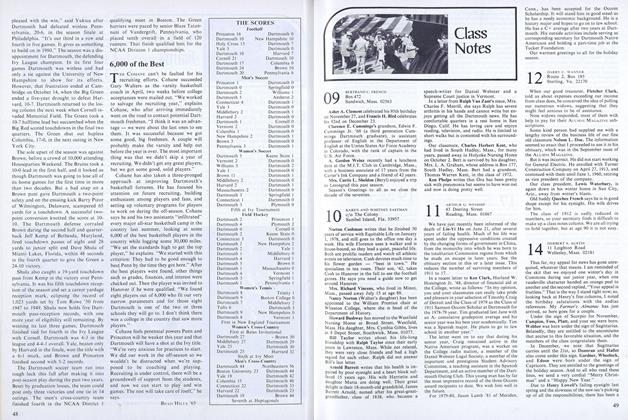

Article6,000 of the Best

December 1979 By BRAD HILLS '65 -

Article

ArticleBASKETBALL

DECEMBER 1969 By JACK DEGANGE -

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH PARENTS

January 1944 By LT. COL. WILLIAM H. COULSON, AUS