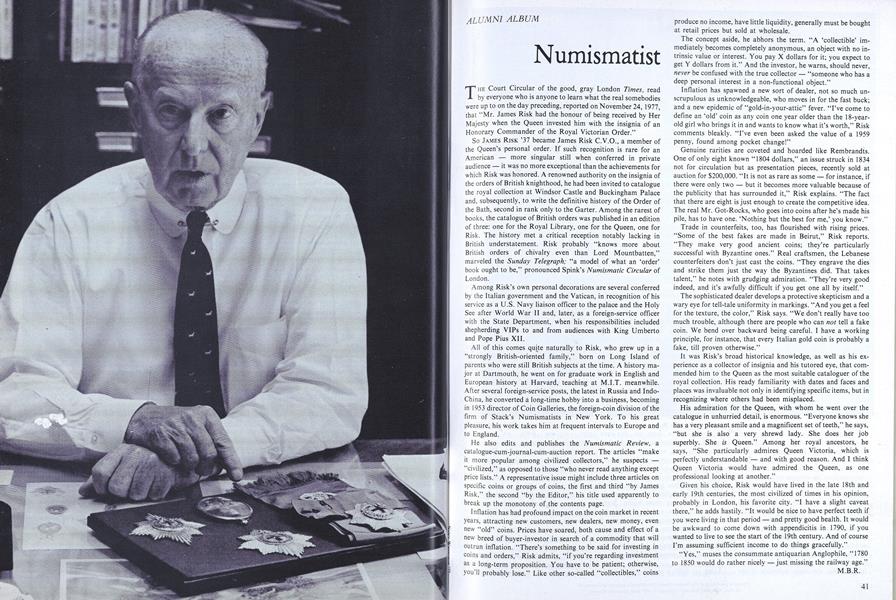

The Court Circular of the good, gray London Times, read by everyone who is anyone to learn what the real somebodies were up to on the day preceding, reported on November 24, 1977, that "Mr. James Risk had the honour of being received by Her Majesty when the Queen invested him with the insignia of an Honorary Commander of the Royal Victorian Order."

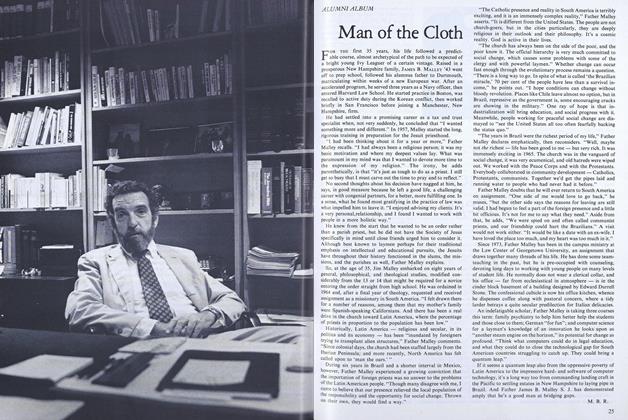

So JAMES RISK '37 became James Risk C.V.0., a member of the Queen's personal order. If such recognition is rare for an American — more singular still when conferred in private audience — it was no more exceptional than the achievements for which Risk was honored. A renowned authority on the insignia of the orders of British knighthood, he had been invited to catalogue the royal collection at Windsor Castle and Buckingham Palace and, subsequently, to write the definitive history of the Order of the Bath, second in rank only to the Garter. Among the rarest of books, the catalogue of British orders was published in an edition of three: one for the Royal Library, one for the Queen, one for Risk. The history met a critical reception notably lacking in British understatement. Risk probably "knows more about British orders of chivalry even than Lord Mountbatten," marveled the Sunday Telegraph; "a model of what an 'order' book ought to be," pronounced Spink's Numismatic Circular of London.

Among Risk's own personal decorations are several conferred by the Italian government and the Vatican, in recognition of his service as a U.S. Navy liaison officer to the palace and the Holy See after World War II and, later, as a foreign-service officer with the State Department, when his responsibilities included shepherding VIPs to and from audiences with King Umberto and Pope Pius XII.

All of this comes quite naturally to Risk, who grew up in a "strongly British-oriented family," born on Long Island of parents who were still British subjects at the time. A history major at Dartmouth, he went on for graduate work in English and European history at Harvard, teaching at M.I.T. meanwhile. After several foreign-service posts, the latest in Russia and Indo- China, he converted a long-time hobby into a business, becoming in 1953 director of Coin Galleries, the foreign-coin division of the firm of Stack's Numismatists in New York. To his great pleasure, his work takes him at frequent intervals to Europe and to England.

He also edits and publishes the Numismatic Review, a catalogue-cum-journal-cum-auction report. The articles "make it more popular among civilized collectors," he suspects — "civilized," as opposed to those "who never read anything except price lists." A representative issue might include three articles on specific coins or groups of coins, the first and third "by James Risk," the second "by the Editor," his title used apparently to break up the monotony of the contents page.

Inflation has had profound impact on the coin market in recent years, attracting new customers, new dealers, new money, even new "old" coins. Prices have soared, both cause and effect of a new breed of buyer-investor in search of a commodity that will outrun inflation. "There's something to be said for investing in coins and orders," Risk admits, "if you're regarding investment as a long-term proposition. You have to be patient; otherwise, you'll probably lose." Like other so-called "collectibles," coins produce no income, have little liquidity, generally must be bought at retail prices but sold at wholesale.

The concept aside, he abhors the term. "A 'collectible' immediately becomes completely anonymous, an object with no intrinsic value or interest. You pay X dollars for it; you expect to get Y dollars from it." And the investor, he warns, should never, never be confused with the true collector — "someone who has a deep personal interest in a non-functional object."

Inflation has spawned a new sort of dealer, not so much unscrupulous as unknowledgeable, who moves in for the fast buck; and a new epidemic of "gold-in-your-attic" fever. "I've come to define an 'old' coin as any coin one year older than the 18-year- old girl who brings it in and wants to know what it's worth," Risk comments bleakly. "I've even been asked the value of a 1959 penny, found among pocket change!"

Genuine rarities are coveted and hoarded like Rembrandts. One of only eight known "1804 dollars," an issue struck in 1834 not for circulation but as presentation pieces, recently sold at auction for $200,000. "It is not as rare as some — for instance, if there were only two — but it becomes more valuable because of the publicity that has surrounded it," Risk explains. "The fact that there are eight is just enough to create the competitive idea. The real Mr. Got-Rocks, who goes into coins after he's made his pile, has to have one. 'Nothing but the best for me,' you know."

Trade in counterfeits, too, has flourished with rising prices. "Some of the best fakes are made in Beirut," Risk reports. "They make very good ancient coins; they're particularly successful with Byzantine ones." Real craftsmen, the Lebanese counterfeiters don't just cast the coins. "They engrave the dies and strike them just the way the Byzantines did. That takes talent," he notes with grudging admiration. "They're very good indeed, and it's awfully difficult if you get one all by itself."

The sophisticated dealer develops a protective skepticism and a wary eye for tell-tale uniformity in markings. "And you get a feel for the texture, the color," Risk says. "We don't really have too much trouble, although there are people who can not tell a fake coin. We bend over backward being careful. I have a working principle, for instance, that every Italian gold coin is probably a fake, till proven otherwise."

It was Risk's broad historical knowledge, as well as his experience as a collector of insignia and his tutored eye, that commended him to the Queen as the most suitable cataloguer of the royal collection. His ready familiarity with dates and faces and places was invaluable not only in identifying specific items, but in recognizing where others had been misplaced.

His admiration for the Queen, with whom he went over the catalogue in unhurried detail, is enormous. "Everyone knows she has a very pleasant smile and a magnificent set of teeth," he says, "but she is also a very shrewd lady. She does her job superbly. She is Queen." Among her royal ancestors, he says, "She particularly admires Queen Victoria, which is perfectly understandable — and with good reason. And I think Queen Victoria would have admired the Queen, as one professional looking at another."

Given his choice, Risk would have lived in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, the most civilized of times in his opinion, probably in London, his favorite city. "I have a slight caveat there," he adds hastily. "It would be nice to have perfect teeth if you were living in that period — and pretty good health. It would be awkward to come down with appendicitis in 1790, if you wanted to live to see the start of the 19th century. And of course I'm assuming sufficient income to do things gracefully."

"Yes," muses the consummate antiquarian Anglophile, "1780 to 1850 would do rather nicely — just missing the railway age."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

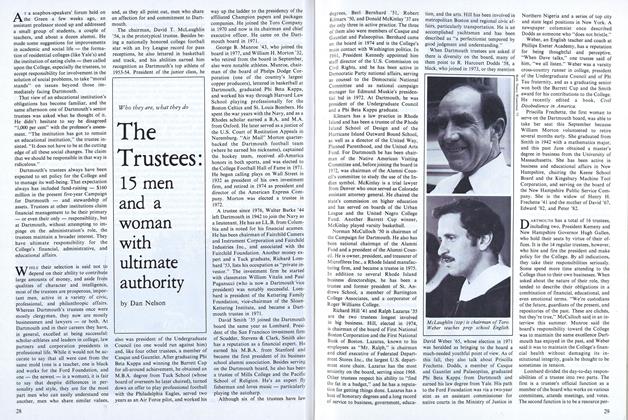

FeatureThe Trustees: 15 men and a woman with ultimate authority

October 1979 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

FeatureTwo at the Top: On being a woman, a wife, a partner

October 1979 By Jean Alexander Kemeny -

Feature

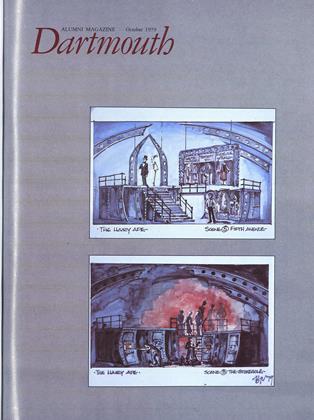

FeatureSummer Rep

October 1979 By Nancy Wasserman -

Article

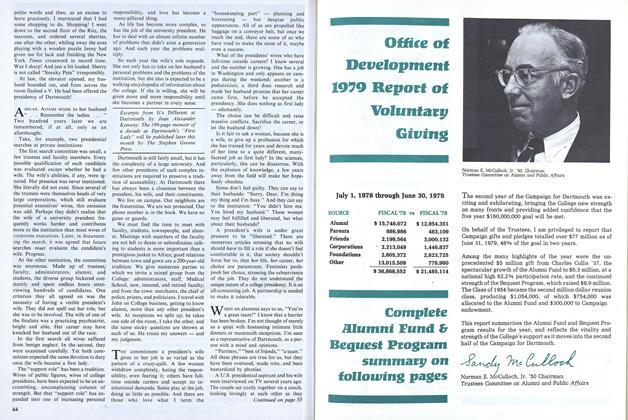

ArticleOffice of Development 1979 Report of Voluntary Giving

October 1979 -

Article

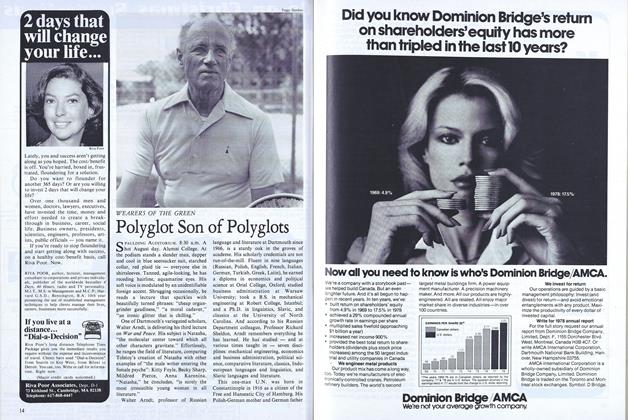

ArticlePolyglot Son of Polyglots

October 1979 By NARDI REEDER CAMPION -

Class Notes

Class Notes1978

October 1979 By JEFF IMMELT