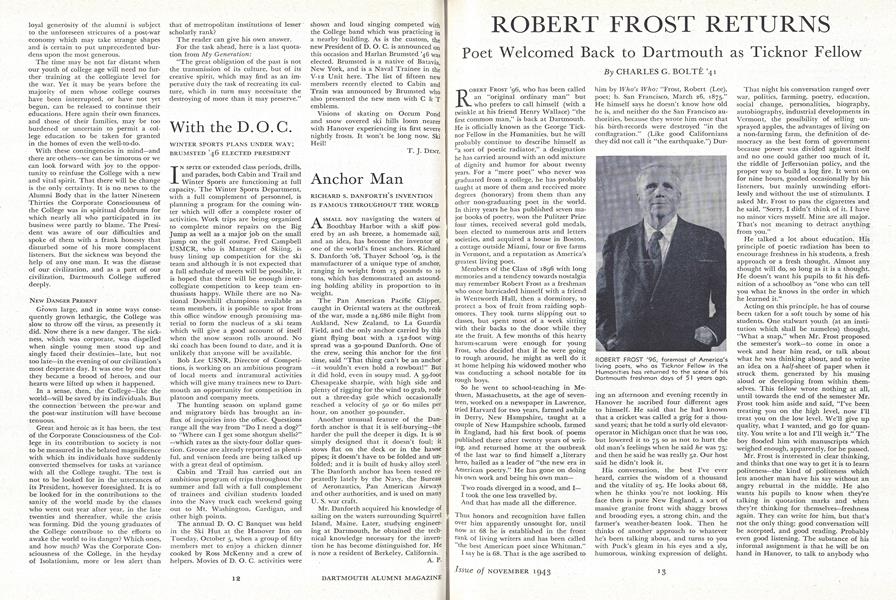

Poet Welcomed Back to Dartmouth as Ticknor Fellow

ROBERT FROST '96, who has been called an "original ordinary man"but who prefers to call himself (with a twinkle at his friend Henry Wallace) "the first common man," is back at Dartmouth. He is officially known as the George Ticknor Fellow in the Humanities, but he will probably continue to describe himself as "a sort of poetic radiator," a designation he has carried around with an odd mixture of dignity and humor for about twenty years. For a "mere poet" who never was graduated from a college, he has probably taught at more of them and received more degrees (honorary) from them than any other non-graduating poet in the world. In thirty years he has published seven major books of poetry, won the Pulitzer Prize four times, received several gold medals, been elected to numerous arts and letters societies, and acquired a house in Boston, a cottage outside Miami, four or five farms in Vermont, and a reputation as America's greatest living poet.

Members of the Class of 1896 with long memories and a tendency towards nostalgia may remember Robert Frost as a freshman who once barricaded himself with a friend in Wentworth Hall, then a dormitory, to protect a box of fruit from raiding sophomores. They took turns slipping out to classes, but spent most of a week sitting with their backs to the door. while they ate the fruit. A few months of this hearty harum-scarum were enough for young Frost, who decided that if he were going to rough around, he might as well do it at home helping his widowed mother who was conducting a school notable for its rough boys.

So he went to school-teaching in Methuen, Massachusetts, at the age of seventeen, worked on a newspaper in Lawrence, tried Harvard for two years, farmed awhile in Derry, New Hampshire, taught at a couple of New Hampshire schools, farmed in England, had his first book of poems published there after twenty years of writing, and returned home at the outbreak of the last war to find himself a.literary hero, hailed as a leader of "the new era in American poetry." He has gone on doing his own work and being his own man—

Two roads diverged in a wood, and I I took the one less travelled by. And that has made all the difference.

Thus honors and recognition have fallen over him apparently unsought for, until now at 68 he is established in the front rank of living writers and has been called the best American poet since Whitman."

I say he is 68. That is the age ascribed to him by Who's Who: "Frost, Robert (Lee), poet; b. San Francisco, March 26, 1875." He himself says he doesn't know how old he is, and neither do the San Francisco authorities, because they wrote him once that his birth-records were destroyed "in the conflagration." (Like good Californians they did not call it "the earthquake.") During an afternoon and evening recently in Hanover he ascribed four different ages to himself. He said that he had known that a cricket was called a grig for a thousand years; that he told a surly old elevatoroperator in Michigan once that he was 100, but lowered it to 75 so as not to hurt the old man's feelings when he said he was 75; and then he said he was really sa. Our host said he didn't look it.

His conversation, the best I've ever heard, carries the wisdom o£ a thousand and the vitality of 25. He looks about 68, when he thinks you're not looking. His face then is pure New England, a sort of massive granite front with shaggy brows and brooding eyes, a strong chin, and the farmer's weather-beaten look. Then he thinks of another approach to whatever he's been talking about, and turns to you with Puck's gleam in his eyes and a sly, humorous, winking expression of delight.

That night his conversation ranged over war, politics, farming, poetry, education, social change, personalities, biography, autobiography, industrial developments in Vermont, the possibility of selling unsprayed apples, the advantages of living on a non-farming farm, the definition of democracy as the best form of government because power was divided against itself and no one could gather too much of it, the riddle of Jeffersonian policy, and the proper way to build a log fire. It went on for nine hours, goaded occasionally by his, listeners, but mainly unwinding effortlessly and without the use of stimulants. I asked Mr. Frost to pass the cigarettes and he said, "Sorry, I didn't think of it. I have no minor vices myself. Mine are all major. That's not meaning to detract anything; from you."

He talked a lot about education. His principle of poetic radiation has been to encourage freshness in his students, a fresh approach or a fresh thought. Almost any thought will do, so long as it is a thought. He doesn't want his pupils to fit his definition of a schoolboy as"one who can tell you what he knows in the order in which he learned it."

Acting on this principle, he has of course been taken for a soft touch by some of his students. One stalwart youth (at an institution which shall be nameless) thought, "What a snap," when Mr. Frost proposed the semester's work—to come in once a week and hear him read, or talk about what he was thinking about, and to write an idea on a half-sheet of paper when it struck them, generated by his musing aloud or developing from within themselves. This fellow wrote nothing at all, until towards the end of the semester Mr. Frost took him aside and said, "I've been treating you on the high level, now I'll treat you on the low level. We'll give up quality, what I wanted, and go for quantity. You write a lot and I'll weigh it." The boy flooded him with manuscripts which weighed enough, apparently, for he passed.

Mr. Frost is interested in clear thinking, and thinks that one way to get it is to learn politeness—the kind of politeness which lets another man have his say without an angry rebuttal in the middle. He also wants his pupils to know when they're talking in quotation marks and when they're thinking for themselves—freshness again. They can write for him, but that's not the only thing; good conversation will be accepted, and good reading. Probably even good listening. The substance of his informal assignment is that he will be on hand in Hanover, to talk to anybody who cares to come in, alumni and faculty as well as undergraduates and trainees. I know of at least two instructors who plan to keep on going to school to him; and I can think of at least one alumnus.

His school is the slow, easy, and revealing one, of experience filtered through a clear and sympathetic mind, expressed in conversation that repeatedly shows "a meaning that once unfolded by surprise as it went.... like a piece of ice on a hot stove."

The figure is the same as for his verse. He says a poem "begins in delight and ends in wisdom, .... in a momentary stay against confusion." His conversation is a stay against confusion at a time when confusion is a drug on the market. Like his verse, his conversation "spreads abroad what our modern world may call the dread disease of sanity." His sanity comes partly because he knows

The need of being versed in country things,

but it is not just farmer's wisdom, nor is it just simple. He is a very complex man and a very well-informed poet. His peculiar distinction is that he combines sanity, wisdom and knowledge with the sense of beauty, clarity, pungency and humor which mark his verse—enough good so that William Rose Benet says, "If anybody should ask me why I still believe in my land, I have only to put this book in his hand and answer, 'Well,—here is a man of my country.' "

One of the open problems for the geneticists' and environmentalists to settle some day is how such a man happened. They may decide that Mr. Frost is so American because he comes of New England stock (dating from 1632), was born on the west coast, and was named Robert Lee by a father who was a Republican turned

A states-rights free-trade Democrat,

a Copperhead and proud of it. They may decide that he is "regional" because of his long years in New England (he says New Hampshire's one of the two best states in the Union, and Vermont's the other), but still "universal" because his mother was Isabelle Moodie, descended from an Orkney Island family. I don't suppose it much matters. There he is, and there is his work —quite unique, original and fresh, so clearly marked "Robert Frost" that he has founded no school and not even produced any first-class imitators.

Mrs. Frost brought her ten-year-old son back to New England when his father, William Prescott Frost, died. He didn't read books till he was fourteen, and started writing verse at the same time. A teacher he liked at Lawrence High School suggested Dartmouth to him, so he came.

He lived in Wentworth in the days when the students hauled their own coal and a dollar went a lot further than it goes today. His room cost him about what a prePearl Harbor undergraduate would expect to spend on a fairly quiet week end in New York. But even that was too much for a hard-pressed mother to pay, Robert Frost thought, considering what he was getting. He was getting Greek and Latin, which he liked, but they didn't seem enough. There was no English course and nobody took any American books to be literature.

He had a pretty good time at Dartmouth, to hear him tell it. There was the adventure of the barricaded fruit, and an escapade involving the cutting of a young theologist's hair so that his scalp showed through in a bright white cross. The boy left college the next day, but they met years later and he was friendly. "Terrible, terrible," the poet says of it now, with a wry smile. He can still reminisce with pleasure of the freshman-sophomore football rush. But—"lt wasn't what I wanted," he says.

When I was young my teachers were the old.

I gave up fire for form till I was cold. I suffered like a metal being cast. I went to school to age to learn the past.

He had already worked in Salem shoeshops and Lawrence woolen mills. Now he taught. His family still wanted him to be —something, or somebody. He tried to please—

I would not be taken as ever having rebelled

—and went to Harvard. He stuck it out for two years. He still wanted to write poetry. His grandfather said, "No one can make a living at poetry. But we'll give you a year to make a go of it.' '

"Give me twenty, give me twenty," said the nineteen-year-old.

A year later he married his co-valedictorian at Lawrence High School, Elinor White. Every one of his books was dedicated to her until she died in 1938, after 43 years of a singularly happy marriage some of whose quality may be guessed at from the love-poems in his first book, the lyric and moving A Boy's Will. They had four children, and shared the hardship and neglect of the lean years when he made a living by farming and teaching, his verse unpublished and his stubborn devotion to it scoffed at:

They leave us so to the way we took, As two in whom they were proved mistaken,

That we sit sometimes in the wayside nook, With mischievous, vagrant, seraphic look, And try if we cannot feel forsaken.

They farmed in Derry for ten years, during which Mr. Frost intermittently taught English at Pinkerton Academy and psychology at the Plymouth Normal School. Mrs. Frost "wanted to live under thatch," so they uprooted themselves and went to England. They farmed for three years at Beaconsfield, a pleasant town in the Home County of Buckinghamshire, and then in Gloucestershire, between those Cotswolds and Malverns that look so much like Vermont hills when the frost is on them.

There, after twenty years—exactly the time he had asked of his grandfather—his first book was published. The first poem is called "Into My Own"—at last, you might say—and it ends:

They would not find me changed from him they knew— Only more sure of all I thought was true.

—lines that could still stand as his motto. In the book he pays heart-felt tribute to "The Trial by Existence," and reports his finding

that the utmost reward Of daring should be still to dare

He continued to dare, although the thinness of material existence was finished with the publication of North of Boston a year later and the critical praise lavished, then and since, on its dramatic poems of tangled, usual lives, condensed and revealed in snatches of conversation; these interspersed with lyrics, comic poems as revealing as the dramatic ones, and other poems carrying the weight and feel of country things.

That pattern continued and developed through Mountain Interval, New Hampshire, and West-Running Brook. Instead of going downhill in later life as so many American writers have, he went on to new things—as indicated by the title of his 1936 Pulitzer-Prize-winner, A Further Range, and its dedication as usual to his wife: "To E. F. for what it may mean to her that beyond the White Mountains were the Green; beyond both were the Rockies, the Sierras, and, in thought, the Andes and the Himalayas—range beyond range even into the realm of government and religion."

That further range has brought him, most recently but, one hopes, not finally, to A Witness Tree, in which there is further wisdom, further playfulness, and further delight. The title indicates the steadfast holding to settled, fundamental things, as we learn from the College Alumni Fund bulletin of 1942 which declares that a witness—tree shows "the location of a corner monument marking the boundary of a farm, in accordance with common practice throughout the earlier-settled parts of America."

That steadfastness and beauty which have made Mr. Frost "America's best-loved poet" have brought him also a flood of honorary degrees and rather general teaching or poetic-radiating assignments at many colleges, including the two from which he failed to graduate. Dartmouth awarded, him the honorary degree of Doctor of Letters in 1933, Harvard a little later. Michigan, Vermont, Wesleyan, St. Lawrence, Yale, Middlebury, Bowdoin, New Hampshire, Columbia, Williams, Bates, Pennsylvania, Colorado, and Princeton have done likewise. He has been professor of English at Amherst three times, poet in residence and fellow in letters at Michigan, Charles Eliot Norton professor of poetry and Ralph Waldo Emerson fellow at Harvard, and now Ticknor Fellow in the Humanities at Dartmouth. This poor scholar has delivered Phi Beta Kappa poems at Tufts, Harvard, Columbia, and William & Mary, a fact which must delight him with its irony. He has even been cofounder of a school—the distinguished summer session of Middlebury College, the Bread Loaf School of English, where he lectures still every year. He has ranged the country's universities, giving lectures and holding conferences, and achieved the academic distinction of being for ten years a fellow of Yale's Pierson College and for two years a member of the Board of Overseers of Harvard.

Throughout all this acclaim he has gone his own way and done what he had to do.

He showed me that the lines of a good helve

Were native to the grain before the knife Expressed them, and its curves were no false curves

Put on it from without. And there its strength lay For the hard work.

This straight course has naturally brought him derision along with honor. He has been damned with faint praise as a "regional poet," his detractors assuming that because he used New England diction his truthfulness was limited to that region; he has been similarly damned as "nature poet," his detractors assuming that because he sang of west-running brooks and the pleasure of being a swinger of birches he had nothing to say about the industrial, urban world where their pre-occupations lay. The free-verse poets and experimentalists have dismissed him as a traditionalist; a charge he has counter-dismissed by saying lightly, "I'd just as soon play tennis with the net down as write free verse."

He did write free verse once, and that two-line poem brought him the most violent denunciation of all—from the radicals.

I never dared be radical when young For fear it would make me conservative when old.

The radicals have written him off as an unreconstructed Tory because he is interested in people not programs, calls (with a mocking laugh) for "a new deck instead of a New Deal," and says

I bid you to a one-man revolution— The only revolution that is coming.

One of the tragedies of the time is that many politically conscious people who see the inequities of an imperfect world have lost faith in progress by the one-man revolution which makes a man a better man, and are pinning their hopes on finding a brave new world through the reforming of institutions—changing the political and economic framework in the belief that people will then grow happier. It is a heresy Mr. Frost has not subscribed to- in fact, he says

I own I never really warmed To the reformer or reformed,

His eyes are not closed to the possibility of advancement through some changes in the existing order—in a recent poem he praises Caesar as an economist who advised dividing up the wealth and starting fresh when things got too lopsided—but he persists in thinking that love, death and birches are important always, even in wartime. He is not so much a political partisan as he is a Vermonter—agin the government, half in play, half in earnest.

There again he infuriates the serious- minded, because his playfulness upsets their calculations. He will not be pinned down; in an age of labeling he refuses to be labeled, preferring to follow impulse, whim, and fancy. His skepticism does not keep him from acute observations on politics and wars:

.... what are wars but politics Transformed from chronic to acute and bloody?

—Clausewitz' classic definition made poetic. But he doesn't think the times are "revolutionary bad" enough to

.... warrant poetry's Leaving love's alternations, joy and grief, The weather's alternations, summer and winter, Our age-long theme, for the uncertainty Of judging who is a contemporary

liarLife may be tragically bad, and I Make bold to sing it so, but do I dare Name names and tell you who by name is wicked?

Instead, he urges that we Build soil. Turn the farm in upon itself Until it can contain itself no more.

I'd be the last to restate Frost poetry in prose, but I submit that "the farm" can be a figure for thoughts, work, or life. Mr. Frost wants to build soil and stand on firm foundations, protected a little from "too much" of "the wide Infinite" by the "Triple Bronze" of the body's hide, a house wall, and a national boundary. For he is, he says, "very national," and doesn't think we can wish ourselves into one world suddenly without bringing all that is "localest and raciest" into a true meeting of interest and character. He is certainly no isolationist—

Something there is that doesn't love a wall —but he laughs a little at those who would make the world over to some pattern. He wants freedom to act and move around and think, without the restraint of patterns imposed on us from above by people who have our best interests at heart. It is not an attitude that leads to violent political action, but it certainly doesn't bar politics, and it tends to eliminate the feeling that the world is chaos. Mr. Frost has a kind of contagious serenity, which induces a certain personal peace of mind in his audience—not a bad quality, an equanimity that rejects "botheration," Mr. Frost's idea of the worst emotion. He says The way of understanding is partly mirth and, bowing politely (to conceal a grin) at those who are shocked by this heresy, adds

.... anyone is free to condemn me to death— If he leaves it to nature to carry out the sentence. I shall will to the common stock of air my breath And pay a death-tax of fairly polite repentance.

His conversation is as irreverent as his verse, modelled on a desire he once owned to that serious things be expressed lightly and amusing things said with a straight face. Thinking and talking as he does, he may be able to give his students, indirectly and by suggestion rather than by precept, the sense of meaning and uprightness he has expressed in such lines as

The best way out is always through and The fact is the sweetest dream that labor knows and "Men work together," I told him from the heart, "Whether they work together or apart."

He lives now in Room 1 at the Inn, latest in a long series of addresses, from which he can look out of many windows across the campus. He wrote President Hopkins, "I am accepting your call back to Dartmouth with pride and satisfaction. Let's make it mean all we can. The callback, I call it In addition to what I do at Dartmouth, I shall belong to Dartmouth in what I do for my publishers and my public."

Taking his own advice, Robert Frost has rejoined the College: Don't join too many gangs. Join few if any. Join the United States and join the family But not much in between unless a college.

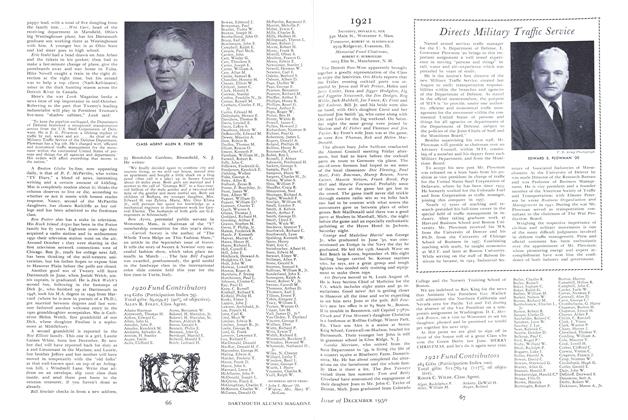

ROBERT FROST '96, foremost of America's living poets, who as Ticknor Fellow in the Humanities has returned to the scene of his Dartmouth freshman days of 51 years ago.

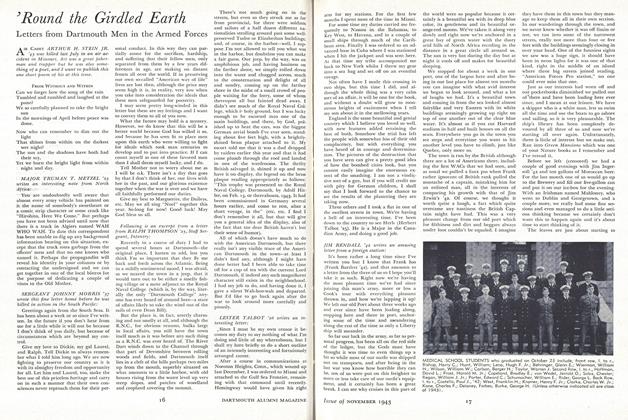

PARTIAL GROUP OF 1945 MEN IN THE DARTMOUTH V-12 UNIT PHOTOGRAPHED AT A RECENT ASSEMBLY AT THE TUCK SCHOOL

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleWILLIAM JEWETT TUCKER

November 1943 By ALEXANDER LAING '25 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorLetters from Dartmouth Men in the Armed Forces

November 1943 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

November 1943 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR -

Class Notes

Class Notes1937

November 1943 By JOHN H. DEVLIN JR., FRANCIS T. FENN, JR. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1917

November 1943 By MOTT D. BROWN JR., DONALD BROOKS -

Class Notes

Class Notes1932

November 1943 By CARLOS H. BAKER, HOWARD W. PIERPONT