Dartmouth Humanist and Prophet of Our Opportunity

There can be no possible academic freedom beyond that which is implicit in academic responsibility. W.J.T.

THE HARD-WON toleration which only now is binding together some of the splintered segments of Protestantism began to show itself late in the last century, in ways that were at times a little odd. It appeared, for example, in the habit of several pastors of southern Massachusetts, who—somewhat forgetting their sectarian fences—used to meet every Sunday evening for common prayer.

In the summer of 1897, such a meeting was held at the home of the Reverend Adoniram Judson Hopkins. One of the visiting clergymen, by courtesy the leader, proceeded firmly to what, according to his own notion, was the evening's vital task. The host's impressionable nineteen-year-old son, Ernest M". Hopkins, had declared his intention of entering Dartmouth College. With ardor and lamentation he was exhorted to do no such thing. Dartmouth, once a reasonably respectable institution, had fallen under the control and spell of "that heretic" Tucker. The guidance of a divine and orthodox providence was besought to turn the young man aside from the stark folly of putting himself voluntarily under so corrosive an influence.

It can be reported to the credit of some others present that there was a divergence of views upon the subject of Dr. Tucker's heresy. But the exact fears of the first exhorter were only too thoroughly justified in later events. As an undergraduate, Ernest M. Hopkins did fall under the influence of the "heretic"—so much so that, immediately upon receiving his diploma, he became Dr. Tucker's personal secretary. After five years the job was enlarged to suit the newly created title: Secretary to the College. But the personal tie still was dominant. Dr. Tucker resigned the Presidency in 1909. The young man who had come under his sinister spell remained .for only a year longer in an administration having somewhat altered objectives.

The other day, recalling the circumstances of his own election to the Presidency, Dr. Hopkins admitted that he had deliberately returned to Hanover at the end of a six-year absence to continue the work which the great "heretic" had begun. The task is still unfinished, as Dr. Hopkins himself would be the first to point out. It will always be unfinished, which is the reason why we must always be getting on with it.

It is not likely that any human being will have both the vision and the means to bring a great human institution close to perfection in one lifetime. President Tucker was aware of this when he sought to reaffirm a kind of mystical bond from each to the next of the "Successors of Wheelock." He tried to deliver, with these words, to his own successor, a concept of the task of the Presidency of Dartmouth College—a concept of unified purpose to which each transient incumbent could add the best fruits of his own capacities. With astonishing forebearance, a scholar and humanist put first things first in the evolution of the new Dartmouth, even when the first things were largely materialistic. He postponed the particular accomplishments which would have been nearest to his heart and thought, in order that he might first lay the humdrum foundations.

When he resigned—far too soon as many thought—the humdrum foundations were firm. The clear and exalted objectives were still on paper. That is the debt which the "Successors of Wheelock" will owe to one of their midway predecessors for many years to come: he did the hard work he was least interested in doing, leaving to them the more luminous triumphs. Yet the things he chose to do were done very well indeed. Dr. Hopkins, seeking to sum up many memories in a recent conversation, put it this way: "He had the common denominators of greatness. It was Dartmouth's good fortune that these were available to her. His talents, however, would have been equally outstanding in any other profession, in industry, government, or politics."

II IT is A FACT which rings strangely in our modern ears that in the lifetimes of the College's present leaders a man who was to become Dartmouth's President could have been put on trial for "heresy." That was what the press of the period persisted in calling the charge, which actually was "heterodoxy," with an implication of breach of trust. To be rightly told, the Andover Controversy, and its culminating action before the Supreme Court of Massachusetts, require the dozens of pages given them in Dr. Tucker's autobiography. But the essence of the case is simple enough, and its implications are of such importance to the welfare of endowed institutions that the more recent generations of Dartmouth men ought not to go unaware of them.

Dr. Tucker, taking office as a professor in the Andover Theological Seminary, had subscribed to the Andover Creed. Later he contributed many articles to the AndoverReviea;—articles tending to express the liberal and scientific theology which everywhere was supplanting an iron Calvinism. One of the trustees, acting with a committee of alumni of the Seminary, charged Dr. Tucker and four of his colleagues with having been false to a creed they had sworn to uphold. Lurking behind the action was the threat of a civil or criminal suit for breach of trust, if it could be shown that money given for the advancement of a specific creed had been accepted, as salary and for other uses, to further the propagation of a contrary faith.

DEFENDED LIBERAL INTENT

Foreseeing the enormous implications of such an action, the defendants raised as a central issue the question whether the strict wording 'of the Andover Creed was intended to prevent any further liberal development of theological inquiry. They contended that the founders of the Seminary had had exactly the opposite purpose, making in the strict creed a statement which was liberal in its own times, and which would prevent succeeding generations from backsliding into a bigoted and more narrow belief.

The decision of the high court upheld the contention of Dr. Tucker and his fellow defendants. But the word "heretic" had been irresponsibly noised abroad, and they were followed by it for many years.

It was a peculiar quirk of fate which gave Dartmouth, the successful defendant in a case upon which the stability of all endowed institutions rests, this close connection with another cause of a counterbalancing nature. The Dartmouth College Case protects all privately endowed institutions from external tampering. The Andover Trial, in which a future president of Dartmouth prominently figured, has had the opposite effect of protecting freedom of conscience within an institution. The Dartmouth College Case upheld the supremacy of the trustees over a hostile legislature. The Andover Trial upheld the integrity of a group of professors against the hostility of a committe of alumni and a trustee.

It would be foolish to claim that the Andover Trial has had specific effects comparable to those of the Dartmouth College Case. It did not reach the ultimate court. The principle which it went far to establish formally, moreover, was less a subject of controversy. But it needed specific champions and a clear precedent, and these the circumstances of the trial provided, even though it almost succeeded in depriving Dartmouth of the great humanist among the Successors of Wheelock.

III DR. TUCKER twice refused to be President of Dartmouth College. Partly it was because he knew that the Andover Trial, with its attendant division of the well-wishers of the Academy, had severely impaired the health of that institution. He felt it necessary to remain in his chair as Bartlet Professor of Sacred Rhetoric, working to heal the many wounds left by the long Andover Controversy. But his main reason was lucidly stated in a letter returning the second proffer of the Presidency:

"The end of controversy, when it is reached, is not rest; it is not freedom even; it is opportunity. The chief object which, with others, I cherished at the beginning, has not been accomplished; it has simply been made possible. It remains for those who contended for freedom to apply the larger Christianity thus gained to the great social needs to which it is fitted; and especially to lead out young men who are entering the ministry, who are for thisvery reason entering the ministry, into those wide and influential relations in which a Christian minister may now stand toward society."

Dr. Tucker's aims were social. As a chief participant in the evolution of the New Theology, he was prepared to fight for the Kingdom of Heaven here on earth. Presently he became convinced that his main objective might better be attained by an enlarged approach. In his autobiography he summed up the transition in this fashion:

"It was becoming more and more evident that the fundamental duties involved in the readjustments of society must be assumed by all the professions, and by men of affairs, some of whom might be expected, under the right incentives, to render a larger and more practical service than the ministry, could the colleges be made to furnish the sufficient motive to the study of the principles of economic justice."

When the third invitation came from his fellow trustees of Dartmouth College, Dr. Tucker accepted the Presidency. It was a period of crisis in the life of the College too. Curriculum and plant were considered largely obsolescent. The faculty in part was being subjected to similar criticisms, and in part they appear to have been justified. In an era of improvement of public enterprises the town was backward and unhealthy. Water mains and sewers were needed. Many other items were wanted, whether they were needed or not.

The new President probably could have had his own way, within reason, concerning any plan that he might have proposed. Starting with a college of modest size, he could have applied himself primarily to the attaining of excellence in academic standards and equipment. The strength of numbers could have come later, if at all. It is the peculiar obligation of those of us who are now members of the administration to remember that President Tucker took the other choice, that—in writing his moving story My Generation —he implicitly placed upon the next generation the responsibility of carrying on the more important part of the task.

AFFIRMED FREEDOM OF ACTION

President Tucker would have been the first to oppose a claim that the codified desires of dead men, however wise and well intending, should constrain the living. His whole position in the Andover controversy is an affirmation of that statement. But I think he would expect it of us that we should justify our accomplishments against the standard of his proposals. At one point he wrote of his satisfaction that the alumni participation in college government had been so happily accomplished. This follows:

"There remains, however, the question of the complete and responsible adjustment of faculties to college administration. The advance in the recognition of faculty rights .... has been very marked But the question of rights is really subordinate to that of responsibilities, and no. satisfactory solution of this question is yet in view."

The discussion continues in terms which seem applicable still. It is an unresolved task in the long evolution of the College. I do not wish, as one standing on the administrative side of the fence, to be misunderstood in this connection. I believe the blame for the dissatisfaction which still exists is to be placed more largely on the faculty side. But the real trouble appears in the existence of any fence at all.

The clarity with which Dr. Tucker saw the problems which would persist in the College might well be considered disheartening by those of us who with prodigious mental labor have managed to produce independent diagnoses of the causes underlying some of our academic ills. We would have saved a great deal of time if we had merely reread My Generation more often.

Dr. Hopkins remembers a little episode which symbolizes this prophetic quality. The - first motor car to reach Hanover turned up one day in 1901 in front of the G & G House. Everyone went down to see and smell and listen to it. When it had noisily departed, the spectators were making the jests that seemed appropriate, but Dr. Tucker and his new secretary walked back to the administrative offices to the foretune of a rapid monologue from the former. He saw a social revolution implicit in that one object, and said so. His mind went intently off on the trail of the nature and direction of that revolution. In the space of a few minutes he had discussed the crime and highway problems that would arise, the industrial and financial changes now due, the subsidiary enterprises which would be called into being.

At times his mind would work in that rat-tat-tat fashion, but the ex-secretary remembers another occasion of a different sort. The two of them were on a train bound for Chicago. They had few fellow passengers. After a large and leisurely breakfast they returned to their Pullman, young Mr. Hopkins rather looking forward to a long chat. Instead of that, Dr. Tucker paused and said, "I think I'll go into this empty section and think for a while."

He did. He thought for a long while. His secretary was puzzled about the whole thing. He could understand a desire to disappear with a book or a newspaper or a briefcase full of notes. But just to sit down and think for an hour or two was a practice which, up to that time, had never come under his immediate notice.

IV IN 1943 Dartmouth College has come to another of its times of crisis, graver if anything than that of fifty years ago. All physical needs within reason have been amply met. The financial structure, judged by the troublous experience of the past decade, is strong and sound. But Dartmouth undergraduates are dwindling away. The V-12 Unit, welcome as it is in every sense, has little connection with what Dr. Tucker called the Corporate Consciousness of the College. When its work is done there may be a period of little activity, brief or long. The superbly loyal generosity of the alumni is subject to the unforeseen strictures of a post-war economy which may take strange shapes and is certain to put unprecedented burdens upon the most generous.

The time may be not far distant when our youth of college age will need no further training at the collegiate level for the war. Yet it may be years before the majority of men whose college courses have been interrupted, or have not yet begun, can be released to continue their educations. Here again their own finances, and those of their families, may be too burdened or uncertain to permit a college education to be taken for granted in the homes of even the well-to-do.

With these contingencies in mind—and there are others—we can be timorous or we can look forward with joy to the opportunity to reinfuse the College with a new and vital spirit. That there will be change is the only certainty. It is no news to the Alumni Body that in the latter Nineteen Thirties the Corporate Consciousness of the College was in spiritual doldrums for which nearly all who participated in its business were partly to blame. The President was aware of our difficulties and spoke of them with a frank honesty that disturbed some of his more complacent listeners. But the sickness was beyond the help of any one man. It was the disease of our civilization, and as a part of our civilization, Dartmouth College suffered deeply.

NEW DANGER PRESENT

Grown large, and in some ways consequently grown lethargic, the College was slow to throw off the virus, as presently it did. Now there is a new danger. The sickness, which was corporate, was dispelled when single young men stood up and singly faced their destinies—late, but not too late—in the evening of our civilization's most desperate day. It was one by one that they became a brood of heroes, and our hearts were lifted up when it happened.

In a sense, then, the College—like the world—will be saved by its individuals. But the connection between the pre-war and the post-war institution will have become tenuous.

Great and heroic as it has been, the test of the Corporate Consciousness of the College in its contribution to society is not to be measured in the belated magnificence with which its individuals have suddenly converted themselves for tasks at variance with all the College taught. The test is not to be looked for in the utterances of its President, however foresighted. It is to be looked for in the contributions to the sanity of the world made by the classes who went out year after year, in the late twenties and thereafter, while the crisis was forming. Did the young graduates of the College contribute to the efforts to awake the world to its danger? Which ones, and how much? Was the Corporate Consciousness of the College, in the heyday of Isolationism, more or less alert than that of metropolitan institutions of lesser scholarly rank?

The reader can give his own answer.

For the task ahead, here is a last quotation from My Generation:

"The great obligation of the past is not the transmission of its culture, but of its creative spirit, which may find as an imperative duty the task of recreating its culture, which in turn may necessitate the destroying of more than it may preserve."

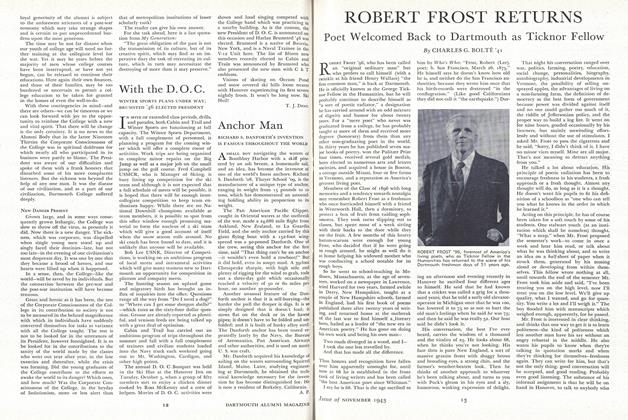

DR. TUCKER IN PRESIDENTIAL DAYS

WELL-KNOWN FIGURES at Dartmouth during Dr. Tucker's administration were, left to right, Dean Charles F. Emerson '68, first Dean of the College; President Tucker; Dr. John K. Lord '68, Daniel Webster Professor of Latin, who served as Acting President the year before Dr. Tucker's inauguration; and Dr. Charles F. Richardson '71, Winkley Professor of Anglo-Saxon and English Literature, best known by the nickname of "Clothespins."

ONE OF THE BEST EXISTING PORTRAITS TAKEN OF DR. TUCKER AS PRESIDENT

AS A STUDENT. Dr. Tucker as he appeared when a Dartmouth undergraduate.

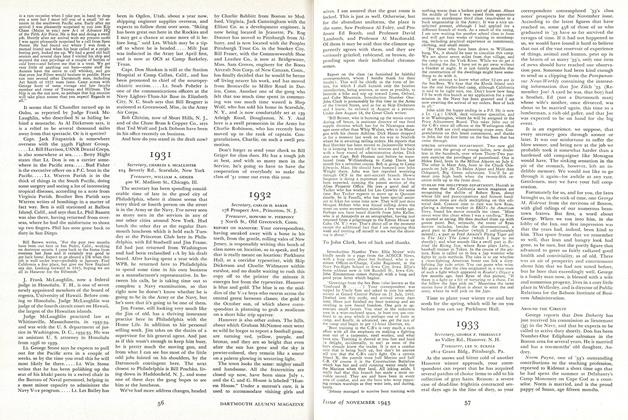

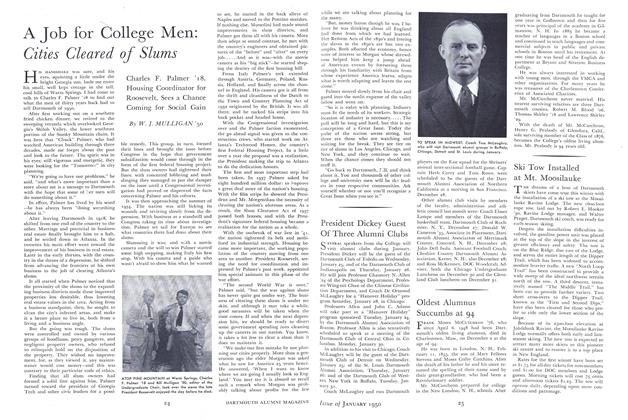

A HISTORIC OCCASION for Dartmouth was the visit of the Earl of Dartmouth to lay the cornerstone of the new Dartmouth Hall in 1904. With this group of Trustees and other dignitaries, the Earl of Dartmouth and President Tucker are shown first and second from the left in the front row. College Hall, then new, is the setting.

The 50th Anniversary of His Administration

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleROBERT FROST RETURNS

November 1943 By CHARLES G. BOLTE '41 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorLetters from Dartmouth Men in the Armed Forces

November 1943 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

November 1943 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR -

Class Notes

Class Notes1937

November 1943 By JOHN H. DEVLIN JR., FRANCIS T. FENN, JR. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1917

November 1943 By MOTT D. BROWN JR., DONALD BROOKS -

Class Notes

Class Notes1932

November 1943 By CARLOS H. BAKER, HOWARD W. PIERPONT

ALEXANDER LAING '25

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters

June 1940 -

Books

BooksREADING THE SPIRIT

January 1937 By Alexander Laing '25 -

Books

BooksHORTON HATCHES THE EGG

December 1940 By Alexander Laing '25 -

Books

BooksUNDERCLIFF. Poems 1946-1953.

May 1954 By ALEXANDER LAING '25 -

Article

ArticleVirtuous Pagan

January 1960 By ALEXANDER LAING '25 -

Books

BooksROBERT SALMON: PAINTER OF SHIP & SHORE.

DECEMBER 1971 By ALEXANDER LAING '25

Article

-

Article

ArticleFACULTY NOTES

January 1916 -

Article

ArticleGraduate Credit School At Tuck This Summer

June 1950 -

Article

ArticleWearers of the Green

July 1974 -

Article

ArticleINTIMATE GLIMPSES OF GREAT MEN IN THEIR OFF MOMENTS AT THE TIRELESS TENTH

AUGUST, 1928 By Stan Jones -

Article

ArticleSki Tow Installed at Mt. Moosilauke

January 1950 By W. J. MULLIGAN '50 -

Article

ArticleThayer School

October 1947 By WILLIAM P. KIMBALL '29.