To The Editor: Tell John De La Montagne not to worry. In the May issue of the ALUMNI MAGAZINE, in "Round the Girdled Earth," he expressed concern lest the war experience was killing his finer instincts, citing his lust to use the bayonet, as an illustration.

I know exactly how he feels. Twenty-five years ago I felt exactly the same, and seriously believed that the loss of the best in me was part of my sacrifice to the needs of war. But I lived to learn that was not the case.

One of the things that distinguishes man from other animals is his adaptability. The city and farm, the arctic and tropics, modern industry and the frontier, war and peace all involve living under certain conditions. And the individual or the group or race that cannot adapt itself to changed conditions soon ceases to exist. What is the right thing to do, or wear, or eat under one set of conditions is the wrong thing under a different set of conditions. Values and emphasis have changed, for what fits, is successful and useful under one set no longer fits, and therefore is not successful or desirable under another.

Actually we mortals live so brief a span, and normally, in so circumscribed an environment, that we tend, in our personal experience to meet only a limited set of conditions, and not to realize that there is, or can be a radically different set of conditions. So we tend to feel that what we have found to be right for our familiar environment is right, period. And the result when people of widely different backgrounds meet is, naturally, misunderstanding. And this is one of the causes of war.

To digress! Those who find life comfortable, and who are well fed become amiable—and, often, ethical. Those who must struggle to exist, and who are half starved are not so amiable—nor so ethical. So, historically, it is to our interest to see that our neighbor is well fed, if we want him to be amiable. The Isolationists forgot that when they demanded the pound of flesh from the Weimar Republic. So now they—and we—are paying for it.

But to return! Those who have known only peace naturally think in terms of the values of peaceful conditions. And it is a very great shock to have to make the adjustment to war conditions—and to war standards.

But what has really happened is merely that the bubble o£ the imaginary world in which they have "lived" has burst with a bang, literally. From then on they will live in a much more real world than they ever did before. And, therefore, whether in peace or in war, their lives will—or at least can—be more useful than previously, for in doing what is right under the conditions existing at any given time, they will do, and give leadership to, such things as not only fit at the moment, but which also take cognizance of the fact that life does contain other sets of values, which must be allowed for. So what they do will more truly fit the real world they live in.

So when the times comes, John, that you can lay down the bayonet, and take up the pen or the test tube, you will be better, not worse, because you have handled the bayonet. You will not have lost your peacetime ideals. But you will have learned better how to work out practical applications of these ideals to the real, very imperfect world in which you live. For the near Utopia in which you thought you lived—even though you did not think it was Utopia—did not exist. And what seemed, therefore, to fit the world, just didn't fit—as we now can see. So, being more realistic from now on, your idealism will be more practical, and therefore more useful.

I am sure my experience 25 years ago was of value to me, through the following years. And I am sure it has also been of value in this return to war condi- tions. And you will find your experience—so disturbing now—has merely burned away the tinsel of an imaginary world, and has not destroyed your real and permanent ideals. Camp McCain, Miss

Lt. Col., Infantry

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

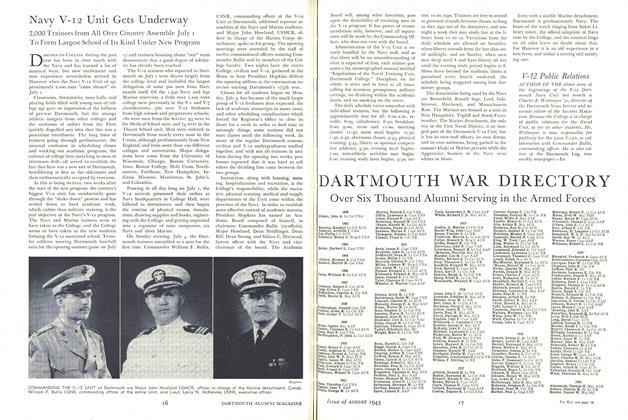

ArticleDARTMOUTH WAR DIRECTORY

August 1943 -

Lettter from the Editor

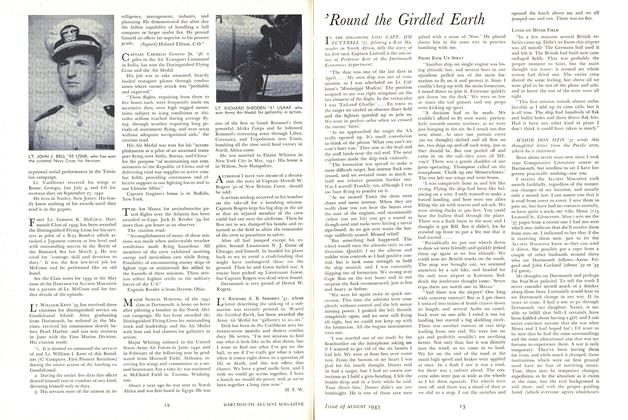

Lettter from the Editor'Round the Girdled Earth

August 1943 -

Article

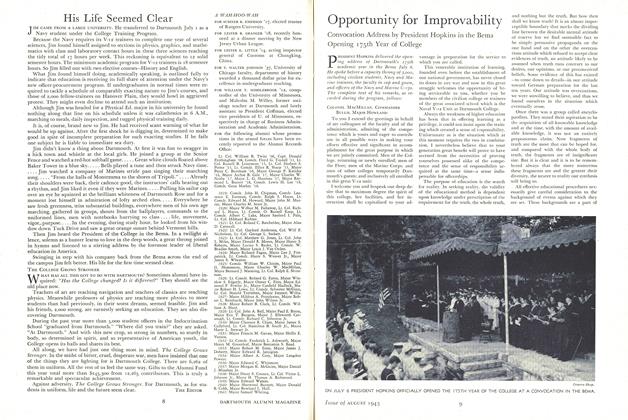

ArticleOpportunity for Improvability

August 1943 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1934

August 1943 By JOHN W. KNIBBS III -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

August 1943 By ERNEST H. EARLEY -

Class Notes

Class Notes1937

August 1943 By JOHN H. DEVLIN JR.

Letters to the Editor

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters to the Editor

JUNE 1930 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters to the Editor

June 1931 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters to the Editor

October 1937 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters

May 1946 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorThe Greening of the Arctic

APRIL 1996 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters

July/August 2011