Former Dartmouth Teacher Suggests New Approach

ON MANY A COLLEGE CAMPUS TODAY faculty members and administrative officers are discussing the function which colleges should now be preparing to perform after the war. Present conditions provide both the stimulus and the opportunity for a review of our customary procedures and our accepted aims; it will be unfortunate if we do not prove equal to the occasion.

Perhaps a fresh approach will be fruitful. Why not begin with the question, What do we want young men and women to become as a result of their college education? In what ways do we want them to be distinguished from those who have not enjoyed the privilege of education beyond the high school? Unless and until we can reach some sort of answer on which there is general agreement we shall not have any criteria by which to judge whether we are or are not doing a good job.

The motive for our appraisal of our inherited practices and objectives must not be a mere anxiety to survive. It must be a real concern that students are to derive definite benefit from what we offer them; we exist only to be serviceable to youth. This may seem to beg the question and to imply that we are not concerned with the benefits which accrue to society. But surely the means by which education can contribute either to social stability or to social progress is precisely the. service which can be rendered to individual persons who, in their own distinctive and recognisable ways, achieve competence, understanding, and sound purposes, which in turn they devote to the common good.

The question is being asked again, as from time to time it must be asked, What is the ideal curriculum? Before we can succeed in enumerating the elements which go to make up an ideal college program we must ask, as realistically as possible, what it is that a liberal education, as distinct from professional or technical training, can Be expected to do for a young person. In one sense, of course, whatever the college does is a continuance of what has been begun in his previous education, formal and informal, in home and school; it is for this reason that the careful articulation of school and college is so important and should receive much more attention than has been customary. What happens in the college years is not that the individual is given something entirely new in his experience but that his powers are extended, his judgment is more broadly based upon accurate knowledge, and his taste is refined by contact with the products of disciplined minds. Certainly, unless at least this happens to a young man attending college, unless in definite ways he . becomes more capable of fruitful thinking, better informed, and more sensitive to defensible standards of feeling and action, his time is wasted.

One of the difficult questions we are now facing in the colleges will be readily appreciated by alumni, particularly by recent alumni. It will be recalled that part, and naturally the earlier part, of a college education is devoted to general education and part, naturally the later part, to the development of powers of concentration. After an acquaintance with the content of courses which are introductory to the more important intellectual disciplines, the student proceeds to focus his attention on a specialized field with the object of acquiring mastery of facts and principles in someone of the "subjects" into which we have subdivided knowledge. This concentration has the value for some students that it lays a foundation for still more highly specialized work on the graduate level; and it has also the value so important to any student, it sharpens up his powers of thought and cultivates his ability to deal with complex data in any field. At least that is what we have hoped of the system of "majors." This fundamental patterna general education followed by some measure of concentration—will probably not be seriously disturbed. But there is one very live question directly related to this pattern: What should be the character and scope of these fields of concentration, these "majors"?

There is a growing feeling in some quarters that in place of majors which call for specialization in single subjects, there will be a call for areas of inquiry which carry to a higher level the general education of the earlier years. It must be admitted that some of the wide-ranging electives offered in the colleges are there not because there is wide agreement on their value nor because there is student demand, but because individual faculty members find it gratifying to offer them. Not considerations of administrative economy but sound educational policy may require in the future that definite objectives- be adopted first and that then the offerings of a college be determined with strict relevance to those objectives. This may mean eliminations.

Possibly some suggestions for future policies, or at-least for discussion, may lie in the approach suggested above in the question, What do we want young men and women to become as a result of their college education? Can we identify some kinds of competence which are important for all educated people? College graduates will be expected to give evidence of the fruits of their privileges, whatever form our society may take.

Let us consider a few kinds of compe- tence and the groupings of subjects which, without too much regard for de- partmental boundary lines, might be con- sidered relevant and effective in develop- ing these kinds of competence. (Such majors would presuppose a general edu- cation which recognised these same com- petences on an introductory level.)

i. Our success as individuals and our contribution to society depend upon our ability to communicate our ideas and our purposes. To this end we need ability in speech as well as in written use of our own language; we are the better for ac- quaintance with one or more foreign tongues, ancient or modern; we need some understanding of the history of lan- guage and of what is coming to be called the science of semantics; we need mastery of the principles which govern clear, forceful, persuasive, and logically valid self-expression. While this is a general need, there are many occupations in which such competence is fundamental. The area of Communication is vastly en- larged today and some of the most significant developments are going on outside the colleges, in the use of radio, films, and various dramatic media. Can anyone doubt that a major in this "area," utilising contributions from various de- partments (English, languages, psychol- ogy and philosophy, speech, art, etc.) would provide for many students the op- portunity to develop competences widely recognized in and needed by society?

RELATED TO PUBLIC OPINION

Such a major would perhaps not prepare a student tor scholarly graduate work leading ultimately to a professorship; but students successful in its disciplines would be valued in journalism, in public service, and in any of the occupations concerned with the development and refinement of public opinion. Elective studies to supplement the systematic major would follow the student's personal interest or vocational intentions.

2. There is a wide range of studies concerned with the structure and needs of society, with the provision of goods and services, with the relationship of one type of community to other types, with order and progress, with the leadership appropriate to various social groups, with the light that history can throw on present choices and future possibilities, and with the function of general coordination which we call government. At present these studies are departmentalized and students may concentrate on one of them without any comprehensive understanding of its relationship to other studies in the same general field. But how, for example, can government be understood today in abstraction from those activities which are analysed in the study of economics, education, invention, or geography, to mention only a few related fields?

As a background for many occupations involving work with people, in organizing and managing business or governmental units, in education, in the social services and the utilities, in journalism, or in the law, what better major could be offered than one in the area of SocialUnderstcmdi?ig?

3. The striking feature of our civilization in the last few decades has been the triumph, at many points, of science over ignorance, superstition, and prejudice. Acquaintance with the methods of gaining, testing, and applying exact knowledge is a sine qua non for an educated person and most college programs now call for contact by every student with at least one scientific discipline on the college level. There is also a generally understood need for men and women who concentrate in someone scientific field. Provision for rather early specialization in scientific studies will probably continue to be one of the features of a good college program. It is to be hoped, however, that in the future such specialization may be enriched and corrected by some study of the history and philosophy of science so that the convenient subdivisions which we have established, and the housing of chemistry, physics, and biology in separate buildings, may not blind the student to the essential community of methods and materials in the principal scientific branches. After all, it is the environment and the equipment of man that science studies, and even an undergraduate should be brought face to face with the fact that every science shades at one point or another into other sciences as its inquiries are pushed to and beyond the limits of our present knowledge.

A major in Scientific Method, with emphasis upon one or another of the specialized branches of sciences, would prove a valuable equipment in many walks of life, even if it were not sufficiently specialized to provide a foundation for higher studies, research, or teaching. It could be provided without undue interference with the task which will undoubtedly and properly continue to be regarded as primary by teachers of science in the colleges.

4. We are today finding pressing reasons to question whether our scientific and technical ability will suffice to safeguard and advance the common good. Science confers powers on those who apply the results of its disciplined research, but the ultimate purposes to be served and the social interests involved are not determined by the scientists; they rest upon the opinions, feelings, attitudes, and beliefs of people who absorb the products of our laboratories. In a time of great changes, when cultures which have hitherto hardly touched one another are now seen to be parts of "one world," it is especially important that a significant number of members of every graduating class be equipped to lead their fellows in the appreciation and interpretation of the controlling factors in social conflict and social progress. There is a high function for those who are particularly well equipped to understand the unity of human need and the different motivations expressed in human activities. At one time such concerns were almost wholly limited to those who left college to enter the profession of the ministry. Today, in addition to those who feel service of the church to be their "calling," there are many people who want to engage in some form of socially useful effort, particularly if it has an educational value, as their calling. They are moved, more or less clearly, by the realization that the common good requires interpreters and exponents of its standards and its aspirations; that both the continuity of all we now hold to be good and the discovery of sounder values call for men and women who can be objective, intelligent, and informed, as well as devoted; and that there are fields of service open to qualified students of the intangible factors of human progress which we call ideals.

NATIONAL COMMITTEE AT WORK

A major in the area of Social and Personal Values would of course be a major in philosophy broadly conceived; if the word is too forbidding or suggests a subject which has been made to seem too remote from life, the philosophers will no doubt be the first to welcome a new name for this broad field. At any rate they now have a national committee at work attempting to evaluate what they have been doing and to suggest what they might do in the future to be more serviceable to youth in the colleges. But such a major cannot be departmentalized nor reserved to the professional philosophers; historians, interpreters of. literature, students of religion, biography, and art, psychologists, and individual teachers in various fields who are notably sensitive to ultimate values, all have a contribution to make, in formal or informal ways, to such a major "area.

These areas of intellectual interest and competence, which have both personal significance and social value, are suggested here as a basis for considering what alternatives. to "subject-majors" might be offered in the post-war college. They are broader in scope and for most undergraduates more functional than either the traditional departmental majors or the topical majors of recent years. They might serve not only the students who have no intention of proceeding to graduate work but also those who expect to enter professional schools; for the law schools and medical schools are now asking for broadly educated men rather than for products of specialized curricula.

Those who evaluate existing college programs and those who plan new curricula must' at any rate concern themselves with the system of majors and with the relation of majors both to the general studies on which they rest and to the capacities which college men are expected to demonstrate when finally they offer society their services and seek a livelihood in return.

PRE-WAR, MID-WAR, OR POST-WAR, FINAL EXAMS IN THE GYMNASIUM KEEP GOING

Dean of St. Lawrence University

Dean Speight wrote this article for the ALUMNI MAGAZINE during a recent visit to Hanover. The outcome of a chat with President Hopkins, the article presents no final answers, according to its author, but is intended as a catalyst to get persons thinking about this vital subject along new lines.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorLetters from Dartmouth Men in the Armed Forces

February 1944 -

Article

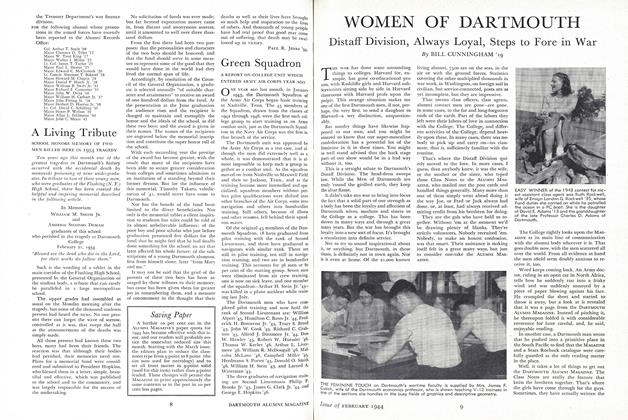

ArticleWOMEN OF DARTMOUTH

February 1944 By BILL CUNNINGHAM '19 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

February 1944 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR -

Class Notes

Class Notes1934

February 1944 By WILLIAM C. EMBRY -

Article

ArticleBUTTERFIELD HALL

February 1944 By LEON BURR RICHARDSON 'OO -

Class Notes

Class Notes1936

February 1944 By JOHN E. MORRISON JR.