Newest Dorm Bears Name of a Dartmouth Graduate of 1839

In 1850 a country doctor in Louisiana, 1 then 32 years old, procured an ordinary blank book with the purpose of writing in it what he termed his autobiography. In the first and longest entry he described somewhat in detail his childhood, his education in preparatory school, college and professional school, and the beginnings of his medical practice. In later years at irregular intervals he noted down incidents of his life which seemed to him important. Eventually he formed the habit of setting down regularly once a year, on his birthday, a brief account of the salient events of the preceding year. This habit he continued until 1892, the year of his death. This "autobiography," now in the possession of the College, makes available a fuller account of his life than is generally possible of a person so obscure.

Ralph Butterfield was born in that part of Chelmsford, Mass. which is now the city of Lowell on March 27, 1818, the son of Ralph and Jemina (Marshall) Butterfield. His father died when the child was two years of age. He was brought up by his grandfather and uncle, apparently possessed of sufficient means to provide for his education. His preparatory school career was somewhat spotty. He attended no fewer than five schools—Chelmsford Academy, Lowell High School, New Hampton, Phillips Andover and Pinkerton Academics. From two of these he was abruptly separated, from one of his own volition he retired in disgust. He writes in the severest terms of the "injustice" inflicted upon him in these institutions. Apparently the difficulty was his lack of response to the intensive tensive religious (or, rather, theological) urgings then common in schools, which caused him to be looked upon by the various principals as an "unfortunate influence" in the school community. At Pinkerton, however, encountering sympathetic teachers, he was altogether happy for the two years of his stay.

Finding the New Hampshire college less expensive than Harvard, as well as the institution selected for further education by a number of his close friends, he entered Dartmouth with the class of 1839. His account of his college course is mainly a story of the pranks in which he indulged. In a few of these he was caught and thereby subjected to the awesome disciplinary admonitions of President Lord; in more of them—surreptitious feasts upon stolen fowl, "blackening" the store front of an unpopular merchant, sinful card playing in his room in the Tontine (in which he was actually caught by the owner of the building, Professor Ira Young, who, in his dual capacity of landlord and officer of the College, evidently allowed his regard for a paying tenant to outweigh his responsibilities as a disciplinary officer, and did not report him), a disastrously unsuccessful expedition to Sharon by night to dig up and steal quartz crystals from the land of a hostile farmer—he narrowly escaped detection, but none the less escaped. At the end of the account is a note of triumph at the success of himself and his friends over the opposition of the "pious" members of the class—and the faculty—in holding a "splendid commencement ball." In general he was not over-devoted to his books, a failing for which in later years he expressed regret, but he did begin at Dartmouth an interest in geology and mineralogy which endured throughout his life.

After graduation he followed the example of many a Dartmouth man of the day by a period of school teaching in the South. However, after a short experience in this calling at Hicks Ford, Virginia, he made up his mind to study medicine. A year at the Columbian Medical School at Washington was followed by apprenticeship under a physician at Lowell and that by attendance at the University of Pennsylvania, from which he received his medical degree in 1843. While at Lowell he fell in love, but his affection was not returned. Apparently this one experience was enough so that he was entirely content to remain a bachelor ever after.

Attracted by the South he determined to enter medical practice in that region. Although he had no acquaintances there, he selected Natchez, Miss, as the center of his activities. Establishing himself with some difficulty, with an almost fatal attack of yellow fever as an added obstacle, eventually he set up a successful country practice near Natchez, residing with a planter and taking care of the inhabitants (slaves among others) of the plantation for his room and board, and wandering far afield for other practice. After ten years, however, he became utterly tired of the laborious and not highly profitable work of a country practice, his health suffered from frequent attacks of malaria, and he turned from his profession to plantation management, working not for himself but for others. This life was far more attractive to him as well as more lucrative so that he finally became sufficiently prosperous to act as a money lender in Natchez and vicinity.

He entered thoroughly into the Southern point of view of the times. Writing early in 1861 he said, "I regard slavery as one of the greatest blessings which ever happened to the sable sons of Africa. They have been civilized Christianized and elevated in the scale of society by it alone. But I will not dwell upon what every wellinformed and honest person admits to be true. A Southern confederacy will most probably be formed and then, when rid of these miserable fanatics who have brought about this state of things, we shall probably go on again harmoniously." The resulting war, with its invasion of that part of the South by the Federal troops in 1863 and 1864 brought to an end his activities as a planter; activities which he never resumed. After the war he was unwilling to engage in plantation management if he must rely upon the labor of free negroes whom he described as "idle, inclined to be impudent so that no money will remunerate one for the trouble he has in trying to make a crop with them." Devoting the next three years to the endeavor to collect debts due to him in Natchez, evidently with some success, in 1868 at the age of fifty he determined to make a new start in life in what was then the far west.

As a new home he selected Kansas City, then a frontier town of some 20,000 in- habitants. At first he entered the real estate business. With some capital at his disposal he made extensive personal investments in land which stood him in good stead in later years. In 1869 he built a "large build- ing" on Green Street for business purposes and storage, and in 1871 he set up in it his own "mercantile establishment" of unspec- ified character. His residence was likewise in this building. The structure was burned in 1881 but at once rebuilt. From this time on his life was one of fixed routine. For the greater part of the year he was busily engaged in the management of his store and his real estate interests, but he always devoted the month of August to a leisurely visit with his relatives in Lowell. His "mer- cantile enterprise" seems to have been of small account, "prosperous but not very lucrative" as he himself described it, but his real estate, with the rapid growth of the city, increased enormously in value so that by 1888 he was able to say, "I find my property here valuable and with other investments renders (sic) me quite well off, not to say wealthy." Keeping religiously free from debt, he was little affected by the various depressions and financial panics of his time. For diversion he found time to devote to his "favorite subject" geology, and collected a "nice cabinet" of mineral specimens of various types. Preserving excellent health nearly to the last, he died in Boston while on his annual visit to New England in 1892, at the age of 74.

After his death in an article from a correspondent in Kansas City published in the Concord People and Patriot it was asserted that he was an eccentric miser and recluse, that his business was merely a shabby second-hand store, and that he was a man of extreme parsimony, exacting in his business dealings, with no friends and few acquaintances. This article brought forth an immediate protest from a friend in the same city. Admitting that he lived his own life as he wished to live it, this friend asserted that he was a man of high probity, of superior intelligence and wide range of interest, agreeable in conversation, with many friends and highly respected in the community.

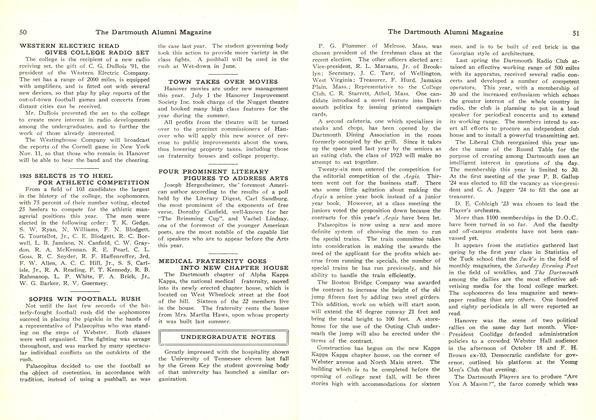

Dr. Butterfield cherished his undergraduate memories and was always fond of his college. Upon the organization of the Kansas City Alumni Association in 1886 he became its first president. In 1889 with some twenty classmates he celebrated at Hanover (apparently his first visit to the community since graduation) the fiftieth anniversary of his graduation; an occasion which gave him the utmost pleasure. At his death three years later it was found that he had made the College the residuary legatee of his estate. The gift was a surprise to the college officers and the amount of the estate was even more of a surprise to all who knew the donor. Under the terms of the will the institution eventually received the sum of $141,526. Save one, it was the largest donation which Dartmouth had obtained up to that time.

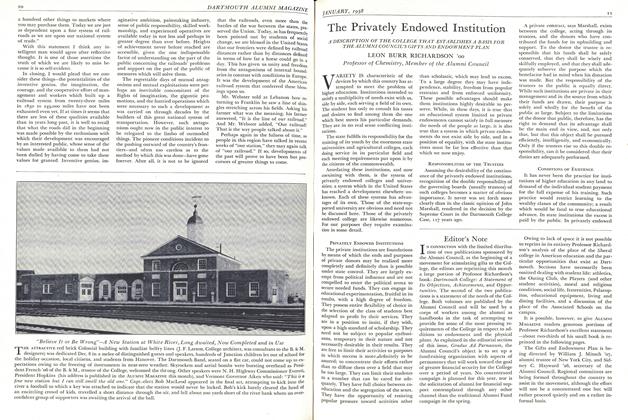

According to the terms of the will the" Trustees were obligated to establish and maintain instruction in paleontology, archaeology, ethnology and other kindred subjects and to erect a building for the housing of specimens illustrating these branches at an expense of not less than $30,000. Dr. Butterfield's own specimens were to be added to the college collection. Accordingly the Butterfield Museum was erected in 1895-1896 at a cost, including equipment, of $87,373. On the first floor it housed the department of biology, on the second geology and ethnology, with a large museum room extending through parts of the second and third floors. It was intended to be one unit of a quadrangle to the north of the college green, a plan that was never completed. Solidly built, it was unfortunate in its type of architecture and its yellow brick construction, both incongruous with the college plant as a whole. Occupying a site which was indispensable for the Baker Library, it was torn down to make room for that structure in 1928.

The latest addition to the residence system of the College, erected on the Hitchcock estate and completed in 1940, was for Dr. Butterfield. It houses 59 students and is valued on the college books at $99,000.

PRESENT BUTTERFIELD DORM (LEFT) AND FORMER BUTTERFIELD MUSEUM, TORN DOWN TO MAKE WAY FOR BAKER LIBRARY.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorLetters from Dartmouth Men in the Armed Forces

February 1944 -

Article

ArticleWOMEN OF DARTMOUTH

February 1944 By BILL CUNNINGHAM '19 -

Article

ArticleTHE POSTWAR MAJOR

February 1944 By Harold E: B. Speight h'28, -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

February 1944 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR -

Class Notes

Class Notes1934

February 1944 By WILLIAM C. EMBRY -

Class Notes

Class Notes1936

February 1944 By JOHN E. MORRISON JR.

LEON BURR RICHARDSON 'OO

Article

-

Article

ArticleREADINGS BY AMERICAN POET

April, 1915 -

Article

ArticleUNDERGRADUATE NOTES

November, 1922 -

Article

ArticleHOPKINS RESOLUTION

January 1946 -

Article

ArticleAlden James '22 now fills the new post

November 1959 -

Article

ArticleThe Hanover Scene

February 1953 By BILL McCARTER '19 -

Article

ArticleThayer School

JUNE 1959 By EDWARD S. BROWN '35